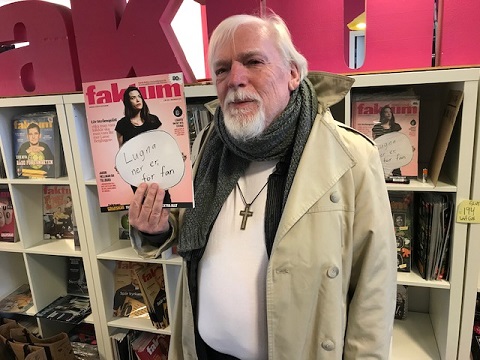

By Sandra Pandevski, Faktum

Last night, at the 2018 INSP Awards, this piece was a double winner, grabbing Best News Feature, as well as being the recipient of the Special News Service Award for the most popular story among street papers. Now, you can read it in full.

A recurring question that Tarana Burke is asked by men is: “Can you teach me how I can do better?”

“’Do I have to teach you how to be human?’ is my usual answer. When a man wants something from another man he knows he can’t be disrespectful or insult him. But when it comes to women that awareness goes away completely,” she says.

Christmas lights are floating above the streets and at the restaurant Brooklyn Bridge Bistro the speakers are bursting with Christmas classics, ‘Last Christmas’ and ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You’. Burke enters the restaurant wearing a bright red coat; her life has become divided into a before and after the hashtag #metoo.

One Sunday morning at the end of October she was lying in bed when her friend tagged her in a Facebook status using #metoo. The friend wanted to know if Burke was the reason behind the post. She wasn’t. But it was hard to ignore the fact that someone was using Me Too virally. She went on Twitter and immediately panicked.

“I thought all the work I had done the past ten years would be overshadowed and that people wouldn’t understand that it’s not just about words. I didn’t know what to do. My friends called me, saying ‘but you were the one who started Me Too’.”

As a 21-year-old, Burke was a leader at a youth camp. When the participants were divided into two groups – “sisters” and “brothers” – a twelve-year-old girl told her “sisters” that her stepfather had raped her. Burke found it difficult to process what the girl had said. It triggered the memories of rapes she herself had repressed. That time she was unable to say “me too”. “I felt guilty and ashamed. But I have also realised that I was only 21-years-old myself.”

Ten years after meeting the girl, Burke is living in Alabama where she founds Just Be Inc, a non-profit organization, where Me Too becomes a phrase used in order to help victims of sexual harassment and assault. She later moves to Philadelphia where she starts lecturing on the topic. After a workshop the students are given a post-it-note where they are asked to write two things they learned as well as the phrase Me Too if they also have been the victims of sexual assault.

“When we got home we saw how many people had written Me Too. Almost everyone. It was horrible and we weren’t prepared for it,” Burke recalls.

Today, Burke is working on creating a durable plan for the organisation. They are going to offer tools online in order to help people host Me Too-events in their home towns covering field work, lectures and workshops with the purpose of preventing sexual violence.

Let’s return to that Sunday in October 2017. Actress Alyssa Milano turns out to be the one who borrowed the phrase Me Too and encouraged the public to use the hashtag when describing their own experiences. The initiative started when The New York Times and The New Yorker exposed famous movie director Harvey Weinstein after he’d spent several years oppressing women sexually.

In order to not let her many years of work stand in the shadow of #metoo, Burke shares her website and videos on social media. A viral discussion arises asking why Alyssa Milano hasn’t directed any attention toward Tarana Burke. But Alyssa Milano responds quickly and gives her credit. Today they are friends.

The day after #metoo goes viral Burke starts to worry about the significance of its spreading. She thinks of everyone sharing their stories. Who is there for them?

“Imagine posting #metoo and no one likes your post or gives you a little heart or says ‘I hear you and I’m here for you’. How would that make you feel? Or if someone ridicules you. or says ‘I don’t believe you, that didn’t happen to you’,” she says as she stirs sugar into her mint tea.

The first two weeks after the hashtag is born Burke gives more than sixty interviews for radio, TV and print. At the same time, she struggles to find her place in #metoo since her Me Too is different from the hashtag. The Me Too of Tarana Burke is a platform for survivors of sexual assault while #metoo has a wider use. But one makes way for the other, Tarana Burke says. On the wooden panel of the cafeteria she draws a line from one side to the other explaining that there is a broad spectrum of gender-related violence. It ranges from sexual harassment to deadly violence because of your gender.

“Sexual harassment creates an environment where sexual violence can thrive. Workplaces, for example, need to have strict limitations on what’s acceptable and what’s not,” she says.

Out on the street, Burke stops in front of a car, watching her reflection in the window as she re-applies her plum lipstick.

In February, she is going to visit Sweden with her 20-year-old daughter Kaia. Burke will be speaking at a conference up in Luleå.

I’m looking forward to it, she says, asking what to wear because she is cold despite the weather being sunny and almost ten degrees Celsius outside. Layers upon layers is the way to go, I say, making her lean back in her car seat and laugh out loud.

The taxi turns onto Chapel Street, where the office of Girls for Gender Equity is located, overlooking the striking view of Manhattan. She started working full time as the program director of Girls for Gender Equity. Its mission is to create better conditions for marginalised groups such as people who are black, gay or trans. On one of the walls hangs a frame containing two questions: What will you accept? What will you refuse?

Burke explains that Girls for Gender Equity is what Just Be Inc would have been today if she had only had the funds to put into the project.

Later that night, she has a meeting with one of Me Too’s donors, The Alliance for Safety and Justice. But the live band that’s playing at the time drowns out everything and everybody. When they wrap up, Burke suggests that they go to a nearby coffee shop.

She takes great interest in the current discussions in Sweden and I tell her that surveys show that 45 percent of men are finding #metoo excessive and that some claim that it takes the fun out of flirting and the joy out of sex. “How about learning how to flirt? It doesn’t have to involve touching or harassing anyone. Think of all the women who have carried shame, guilt and fear for decades, who have looked at themselves in the mirror and felt that their value has been reduced. Sit in it!”

It doesn’t have to do with having a daughter, a wife or being a woman, Tarana Burke says, again pointing out that it’s all about being human. “That’s how change happens, by staying in what’s uncomfortable,” she says, slapping her palm against the table and saying, once more: “Sit in it!”

I show her the list of the many different industries that are joined in calling out sexual harassment and assault. “Wow, are all of those hashtags? Can you send them to me? I’m so fascinated by how these women are supporting one another.”

She doesn’t see the same support in #metoo in the United States, but rather a divide between black and white people. She is saluted by the black community but since many of the women who have testified in conjunction with #metoo are white, rich and good looking, a lot of black people are avoiding the hashtag, not using it to the same extent. When Burke heard about the hashtag #blackgirlstoo, she was hurt that black people didn’t feel that #metoo belongs to them, despite the fact she is the one behind it.

“I didn’t think we needed more hashtags. But seeing what’s going on in Sweden, I’m starting to rethink that,” she says, looking down at the table and going quiet for a moment. “Maybe I ought to support #blackgirlstoo.”

She’s afraid that marginalised groups will be left out, not keeping up with the movement. That those with privilege will be the ones who are heard the most. “The people with the strongest voices have to invite the rest. Some of them understand that, other people think that they can speak for ‘those who have no voice’. But we all have voices, some are just too loud for the others to be heard.”

Her other concern is that Me Too will be used for political gain and that the testimonies thereby will lose their credibility. For a durable change, Burke believes in taking it slow. She wants to introduce extensive sex education, starting in preschool when children are aware of gender and able to understand the meaning of boundaries. In every grade the teaching should expand and be based on human rights.

The clock is almost ten; Burke yawns and picks up her cellphone in order to check if her daughter Kaia has tried to get in touch. “You should have met her,” she says, leaning forward across the table in order to show me a picture of her daughter from last week, preparing for her 20th birthday.

Kaia knows what her mother has gone through and has had a rough time herself. “I’m glad that we get along so well and that I can offer her the kind of support that my mother didn’t show me.”

It wasn’t until Burke was in her 30s that she talked to her mother about the rapes. There was never any room for her personal experiences, she explains.

As I ask my final questions about Kaia’s father, the song ‘Fix You’ by Coldplay is playing in the background. They met in high school. He was the only person she could imagine starting a family with because she trusted him, trusted that he would protect her. But she didn’t feel trust in him enough to confide in him what she’d been through. That she, as a child, had been raped multiple times.

“For a long time I blamed myself. I didn’t distrust men, I distrusted myself. To others I could say ‘it wasn’t your fault’ but I couldn’t say that to myself.

“But loving has been hard for me, I just haven’t found the right one,” Burke says, laughing.

We take a selfie outside the coffee shop in Madison Square before she takes a cab home to Harlem.

During a poetry night at Bowery Poetry Club in Soho, a young black girl takes the stage. She dreams of other things, of being touched and not abused.

Later that night another guest is applauded onto the stage. They speak of the sexual violence they’ve suffered, raped by their own father. The evening ends in their words: “We woke up without these experiences. But when we leave here tonight we carry them with us forever.”

Translated from Swedish into English by Liv Vistisen Rörby

INSP members can download this feature from the INSP News Service here.