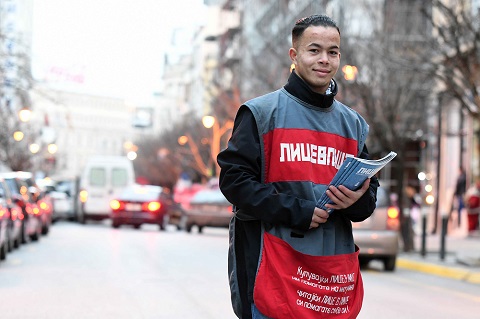

By Sandra Pandevski, Faktum

Content warning: This story contains descriptions of psychological and sexual abuse, and references to drug consumption and self-harm.

It is shortly after lunchtime. People come and go through Malmö’s Caroli shopping centre. Over by the entrance sits Anita, laughing. In front of her is another woman, who is also laughing. Her name is Ingrid Olsson, and she lives nearby. Ingrid often comes shopping here and always stops by to chat about life with Anita. And to take a quick drag on a cigarette.

Outside the entrance to the shopping centre, Anita and Ingrid grab a cigarette packet and light up. “We talk about everything and very private things,” Ingrid says. “We’re both getting on and have seen it all. Good and bad things.”

It’s cold outside. When she has smoked her cigarette down to the filter, Anita dives into her cigarette packet for another. Ingrid tells us how she sometimes sees Anita whoosh past on her electric wheelchair when she’s standing in the supermarket checkout queue. “One vroom and she’s gone!” Ingrid grins. Anita replies by explaining that she often needs to get to the toilet quickly because she takes diuretics. This is one of the reasons why she ended up with a pitch at the Caroli shopping centre when she started working as a Faktum vendor almost three years ago.

Here at Caroli, Anita has met the friends that she previously lacked in life – those who ask how she’s feeling and who open themselves them up to her. “There are always people around me,” Anita says. “They always have something they want to talk about. Many start off with the weather and then get on to talking about other things.”

Some people can’t afford to buy Faktum but still hang around to chat. Others buy more than one copy because they can. Ann Sidbrandt is one of these people. She asks Anita how she’s doing because she hasn’t seen her for a few days. Ann tells us that she even called Faktum’s office to check that everything was alright. “You’re my pretend mum!” says Anita, laughing. “I had a doctor’s appointment and then there was a new issue release at Faktum, and then it usually takes a while before you come out to sell it.”

Ann Sidbrandt buys the new issue. They part after giving each other a goodbye hug.

Anita looks at her mobile – it’s a Nokia handset that Anita thinks must be around 20 years old and isn’t anything like what kids play online casino ohne limit 2023 on these days. It’s getting late, so she starts up her wheelchair and drives to the entrance on the other side of the building. Outside the shopping centre, Anita takes another cigarette from her bag and pops it into her mouth, only the wrong way around. She quickly corrects herself, but only has time to take a quick drag before Jocke (Joakim) from the travel service is here to drive her home.

In the car, they talk about today’s street paper sales. Anita tells Jocke that sales were better yesterday, while turning to point out the window. A large white building comes into view as we speed along the highway. It’s a former women’s prison, now empty. We discuss whether it should be turned into housing.

“Everyone could have their own cell,” Anita says.

Anita herself has lived in the same place for the past 28 years – a studio apartment in Segevång, Malmö. When we arrive, she opens up the gate and uses an electric ramp to reach the letter boxes. “Let’s see if I’ve got any love letters,” she winks. Her mailbox is empty. “Ah, but no post is good post!”

When we reach her front door, I notice a sign that says: No advertising thanks, only visitors! Inside her flat there is a kitchen, a bathroom, and a larger room furnished with a single bed and a TV stand. There is also a large grey armchair and footstool, which she bought with the money she earned selling Faktum. Anita tells me that she has never actually sat in the armchair, because she can’t get out of it. It’s just there to make things look more homely. The cushions on the furniture are neatly arranged and the flat is squeaky clean – well, except for the inside of the microwave, she admits.

Anita confesses that she is a stickler for cleanliness: “I’ve always been a cleaner, or – as I call it – a ‘well being engineer’. If your surroundings aren’t clean, then you can’t thrive. Those who clean ‘engineer’ their wellbeing around themselves. That’s why I use that phrase.”

Anita recently turned 79, which is an age she never thought she would reach. Anita has tried to take her own life on many occasions. She threw herself in front of a bus in 1980. She ended up with a ruptured spleen and a crushed hip joint.

“It wasn’t planned, but I couldn’t take it anymore,” Anita says. “I just couldn’t take it anymore. Everything that had happened to me. I was just five years old when I was sexually abused by my stepfather. He masturbated into my mouth, but at the time I didn’t understand what he was doing. When I told my mother about it, she said that I should let him have some fun. She offered him us girls. My sister committed suicide at 46.”

Life’s torments have sentenced Anita to what she calls ‘life imprisonment’. She says this because the body remembers, and the memories never leave. “God, how I hate him. My mum too!” she says, crossing her arms around her body and hugging herself.

Anita grew up with two sisters and two brothers. Today, only one sister and one brother are still alive. They rarely see each other but do keep in touch. Her brother is a very kind person who has previously helped her out financially. He no longer needs to.

“I have a horrible memory that shows how awful my mother was,” Anita says. “I shudder when I think about it – look, you can see me shaking,” she says, holding out a trembling hand.

“We used to have a cat, and it had kittens,” she continues. “My mother put them in a sack and drowned them in a tub of water. They cried out in distress, and I became completely hysterical. Then she said: ‘I can do it to you too if you aren’t careful’. She kept holding them under until they went quiet.”

Her miserable home-life destroyed Anita. She was expelled from school and had difficulty concentrating. She doesn’t remember if she managed to pass any exams. Her marks would have been terrible if she did. When Anita was 14, a neighbour noticed what was happening to Anita, and this led to her stepfather being convicted.

Anita ended up in an children’s home, which she did not like. The years that followed were filled with escapes and petty theft. She and some friends stole a car and went to Stockholm, burgled summer homes and burned furniture to keep warm. They siphoned petrol from cars. Begged. But they were known to the authorities, and so it did not take long before they were found.

Anita tells me that she was then placed in a foster home, with ‘a kind woman’. Despite this, Anita found herself acting out. “I didn’t want her to get money for having me, so I gave her a hell of a time.”

Fruit and sweets are dotted around Anita’s apartment. There are apples and clementines, large Plopp chocolate bars and a bowl filled with caramels and chocolate hearts. Anita doesn’t eat them, though. “I buy them to put out for visitors because I want to be like everyone else,” she says. “Sometimes I’ll pinch a caramel, but I throw most of them away when they go stale.”

Eating gives Anita anxiety. It was following her stepfather’s abuse that she began to starve herself. Her mother would force her to eat, but this just made her throw up. Anorexia and bulimia have been part of Anita’s daily life since the age of seven. Her propensity to self-harm increased over the years, and her arms became covered with scars. Anita has previously told Faktum how, at the age of 70, she traded in her scars for tattoos. The first one was a large rose on the right side of her neck. Nowadays, however, she can’t get any more tattoos because her skin is too thin. If it weren’t for this, she would like to make one last note on herself and write, “Enough!”

Words have always been a way for Anita to vent her frustrations. An etching on one of her arms alludes to the coping mechanisms that have helped her: “Humour and tears are the body’s ventilators”.

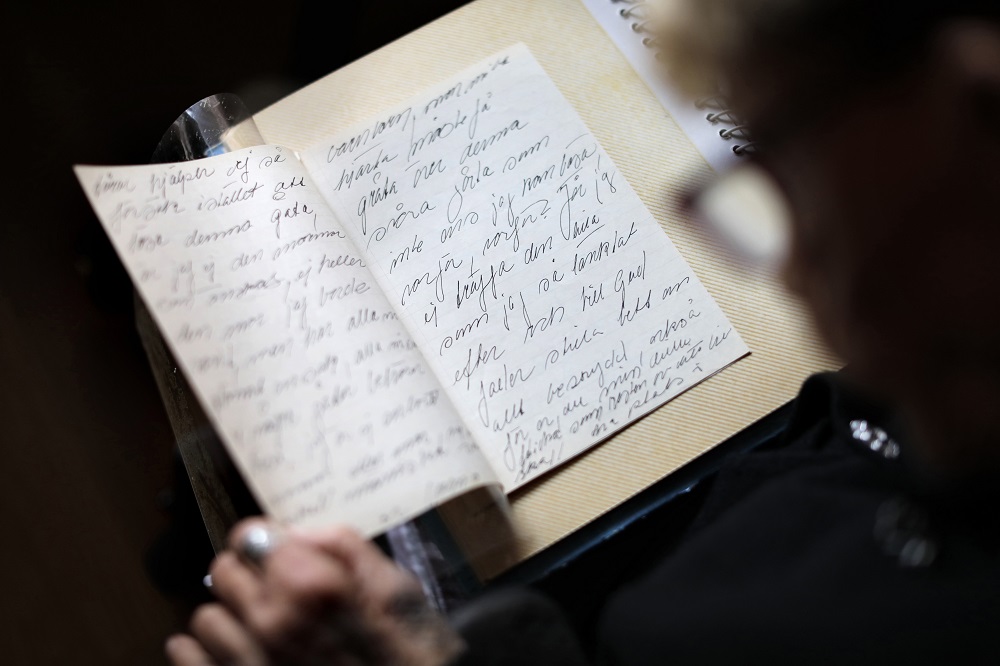

“I have been writing since I was a child – always scribbling away, although none of it’s pretty. I needed to get shit out,” Anita tells me, as she moves into the other room. She takes some folders out of a black cupboard – one red, one with a picture of two puppies on the front, and one blue, decorated with a flower pattern. The binders’ covers are more cheerful than their contents, as we will soon find out.

“Can you get my reading glasses? The ones with the red frames,” she asks. She tells me that she hasn’t read through these folders for “a hundred years”.

She opens up the blue one. She finds letters that she wrote to her children, but never sent. Some pages are handwritten and difficult to decipher; others are typed on a typewriter. Anita reads aloud, from top to bottom, without stopping. There are diary excerpts about her childhood, alcohol, the men who let her down, her children, money. There also many sections about finding strength and fighting back against her past. She reads one entry from Wednesday June 22, 1994:

My illness [alcoholism] is severe – very severe – but there is another one that is not as severe but just as dangerous, and that is to feel sorry for yourself and give up your fight for a better life.

I, Anita Gunnel Rinkovec, absolutely do not intend to give up. I fight for a better life where there is room for love, community, warmth and quality of life, where I am me and no one else, and not a clown constantly trying to satisfy everyone around me. Now it’s time for my life and my needs to come first, which is more important than anything else.

Anita picks up the folder with the puppies on the front and turns to the first page. She falls silent. There is a picture of her that was taken on a trip to Finland. That was back in 1990.

“I was good looking, and I’d knitted that jumper myself,” she says. “This was supposed to be my last journey, to death. I was going to kill myself – to jump off the boat. But for some reason I got drunk instead and met a guy. We danced and had fun. Today I know that it was lucky that I never did what I went there to do.”

Anita visibly clams up as she puts down the folder. “This is emotional,” she sighs. “Seeing stuff from that Finland trip shakes me up. I haven’t thought about it for many years. I wouldn’t be alive today [if I’d gone through with my plans]. Really.”

In May this year, a selection of Anita’s views on life will be published in the third issue of Faktum Novell. She asks me to go through the folders – to pick out the ‘best’ parts and get rid of the rest. She never wants to see the folders again. “I can’t bear to have them here,” she grimaces. “When I die, you should burn them!”

We go back into the kitchen. Anita needs a cigarette. Pinned up on her kitchen walls are lots of postcards with different motifs. There are some with greetings, like ‘Thinking of you’ and ‘Congratulations from us’, and postcards of cats, dogs, tulips…

“Most are from Karin, my best friend,” Anita smiles. “We’ve known each other for almost 40 years. It was Karin who helped me with my anorexia. I started inviting her to dinner – or rather, she ate my dinner while I drank my beer.”

Anita describes Karin as her polar opposite. Karin, who has also been Anita’s doctor over the years, does not smoke, drink or eat meat. “We are so different, but when we met, we clicked instantly,” Anita says fondly.

Anita herself also likes to send postcards. At Christmas time, Faktum customers receive Christmas cards from her. She buys them at the tobacco shop in Caroli and writes personal greetings. In addition to the pen, the brush is also close to her heart – or rather it was close to her in the past. Anita used to paint more back in the days that she drank. There is a bottle of Seagram whiskey on the kitchen counter, but she rarely has a sip these days.

She takes out a small photo album which contains abstract works of art in bright colours. One she calls ‘Crazy’, another ‘Pain’ and a third ‘My Food’. A sprawling red-pink, hibiscus-like artwork is called ‘Evil’.

Alongside the postcards wallpapering the kitchen, there are also photos of people. One is of a man, reclining. He’s an old lover.

“And look! There’s me and Anna!” she says. Anna is one of her four daughters. In the photo, Anna is holding onto her mother, who is sitting in a chair. They are both looking straight at the camera. “She was my darling girl,” Anita says, her words radiating warmth. “We were the most alike. She lived with a foster family and with me. They used to invite me to Sunday dinner.”

Anita admits that it’s hard to talk about her. “I remember her being mean, but very cute,” she says. “It was the drugs that made her like that. We got in touch again in recent years – we went out to eat, because she enjoyed eating. She also wrote a lot, so beautifully and profoundly.”

Anita shares a message from her daughter with me: “You are like the rolling skies, wild, good and lovable. You are my mother, and I love you for who you are. You are a vulnerable person, tender, loving, tender, and kind. For all eternity you are within me, your own daughter.” It is signed, “To Anita, from Anna, 1993.”

Anna died of an overdose aged just 46. She was homeless at the time of her death. Overdoses have taken three of Anita’s children. “I was ill,” Anita says. “I couldn’t take care of them.” A long silence follows.

Anita tells me that she is not in contact with her remaining living daughter. “She is disabled,” she says. “I had her at home for a few years, but she was too strong for me and aggressive.” Today, she lives in a supported residential home.

In the largest room of Anita’s home there is a framed photo of her youngest daughter. The picture was taken just before she died, at 24 years old.

Anita has both grandchildren and great-grandchildren, but she has no contact with them. She has met one grandson, Christian, once. He is 16 now. “I’ve written a book for him,” she tells me. “But he hasn’t got it yet.” She takes out an album from one of the kitchen drawers. It says, “To Christian, from Jaja” – meaning ‘grandmother’ in Greek, the nationality of Christian’s father. In the book, Anita shares her thoughts about not seeing him.

Anita stops talking to frantically scratch her back with one hand and then the other, in the attempt to reach the spot that is troubling her. “Argh, the itching!” she exclaims. “That’s how they discovered that I had kidney problems: I was itching so much. It’s unbearable.”

Anita’s kidney failure means that she only has a few months left to live. She refuses to have dialysis treatment. She thinks that it’s not a dignified way to live out her last days. Better to die the natural way rather than having to be in the hospital several days a week, for five hours at a time, being completely “conked out” for most of it.

“I could live for another two or three more years with dialysis, even ten,” Anita says. “But what would that be like? I wouldn’t be able to work at Caroli anymore, and what would my quality of life be like then? They’re going to do some new tests and see how far gone the whole thing is – but I’ll never see 80.”

“Nothing really” is Anita’s response when I ask her what she will miss about life. She pauses and then continues. “Or actually, yes, I will miss selling Faktum. And Karin. She is over 80 years old now, and I told her that I would go on dialysis for her sake. Up until she passes away, I told her, just because I don’t want to leave her alone among all these predators on earth.”

I ask Anita what Karin’s response was. “She doesn’t want me to do it for her, but for my own sake,” she says. And so Anita’s decision to refuse treatment remained unchanged.

I close our conversation by asking Anita how she has got through all of the darkness she has experienced in life. “I believe in him, Jesus,” she says, looking up with a smile.

“If not for him, I would not be sitting here today,” she continues. “I’m not a fanatic, but I think there’s a meaning to everything that happens. There are so many people who come to me and tell me about their problems. I don’t see myself as a salesperson when I’m out selling Faktum; I’m a psychologist, pure and simple. I wasn’t meant to die earlier in my life. I was needed down here, to help other people.”

*Anna and Christian’s names have been changed.

Translated from Swedish by Phoebe Harrison

Courtesy of Faktum / International Network of Street Papers