Those familiar with street papers – people who buy them, people who read them, people who make them, people who support them – know what a street paper is: an enterprising solution to poverty, a sustainable income provider to those unable to find a job, an empowerment tool for those who are vulnerable or marginalised, on the fringes of society.

But it is the people who sell these magazines and newspapers – on the streets, outside shops, in train stations, at busy intersections – who know what a street paper truly means, what it represents.

The International Network of Street Papers asked these people – variously called sellers, salespeople, vendors, ‘Spokespersons for Culture’, camelots, Verkäufer*innen – what a street paper is to them, personally. Responses were varied and came from a vast geographical span, highlighting the diversity of people and ways of thinking amongst this network. In this second instalment, people from North Macedonia to Canada have their say.

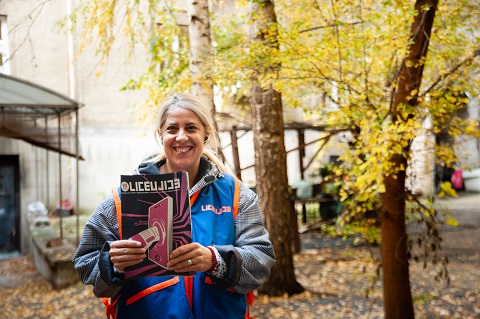

Memet Kamber sells Lice v Lice in North Macedonia

“For me, street papers mean a lot more than just a job to go to! It means inspiration – I enjoy rap and hip-hop music and, while I’m on the streets, it inspires the songs I write. Communicating with different people is very important – it gives me a sense of belonging. That moves me!”

![Lice v Lice's Memet Kamber. [Courtesy of Lice v Lice]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/INSP_Holiday-feature-2021_9.jpg)

Nenad Srbinovski, 30, sells Liceulice in Belgrade, Serbia

“The street paper relaxes me. I like to sell it and I’m good at it, and that calms me down and makes me happy. I got used to both nice words and criticism.”

![Liceulice's Nenad Srbinovski. [Credit: Sara Ristic]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/INSP_Holiday-feature-2021_10.jpg)

Agathe Melançon, 51, sells L’Itinéraire in Montréal, Québec, Canada

“For me, L’Itinéraire is belonging. I feel that I am part of a great team. We get a helping hand and benefit from having people around us, breaking out of isolation, talking with people, having a space to communicate, especially when we write for the street paper. It allows you to have a little extra income and a flexible schedule. And street papers create awareness of the reality of people living on the street and in poverty. L’Itinéraire helps me a lot: I sometimes take grocery bags from Moisson Montréal, a food bank that partners with our organisation. The intervention workers are good listeners. They helped me after the death of my mother recently. It’s good to have people around who don’t judge me and take me as I am.”

![L'Itinéraire's Agathe Melançon. [Courtesy of L'Itinéraire]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/INSP_Holiday-feature-2021_11.jpg)

Mark Irvine, 70, sells Megaphone in Vancouver, Canada. He also takes photos for the street paper’s annual ‘Hope in Shadows’ calendar

“Street papers – especially Megaphone – foster curiosity in what’s going on in your own backyard. The focus is on local happenings, achievements and developments in the neighbourhood. Selling Megaphone has given me a different perspective. It has also made me a more outgoing person. It’s the interaction with customers, most of whom I don’t even know by name, even the regular ones, that make selling the magazine all worthwhile. They are really helping me come out of a hard period. It has been a bright light in a dark time. It’s become about more than just making money, it’s a chance to connect with the community.”

![Megaphone's Mark Irvine. [Courtesy of Megaphone]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/INSP_Holiday-feature-2021_12.jpg)

Martin sells Nový Prostor in Prague, Czech Republic

“The street paper means a lot to me. I had an accident, I was hit by a car, then I was in coma and I deal with lifelong consequences. I feel dizzy and can’t do hard work, so I’m glad that I can sell Nový Prostor. If it didn’t exist, I wouldn’t have money to live.”

![Nový Prostor's Martin. [Credit: Michal Zeman]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/INSP_Holiday-feature-2021_13.jpg)

José Fernandes Junior, 54, sells Ocas” in São Paulo, Brazil

“The street paper saved my life. That’s not an exaggeration. It was a way out for me – it helped me get out of a catastrophic situation when I found myself homeless. It has given me work, dignity and several friends.”

![Ocas" vendor José Fernandes Junior. [Credit: Luisa Santosa]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/INSP_Holiday-feature-2021_14.jpg)

Claudo Bongiovani Azevedo, 71, sells Ocas” in São Paulo, Brazil

“Ocas” changed my life. It has been fundamental for me since 2004. It entered my life in a dark period, when I was living on the streets. I lived in that situation for 11 months. But by selling this magazine, I was able to change my life because with the money I made I was able to pay for a place to live and food to eat. I became a normal man that was living collectively again. It allowed me to study, to learn English, to become a published writer. I am going to be a member of the Ocas” project for as long as I am alive and as long as the magazine is released.”

![Ocas" vendor Claudo Bongiovani Azevedo. [Credit: Luisa Santosa]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/INSP_Holiday-feature-2021_15.jpg)

Roberto Francisco dos Santos, 54, sells Ocas” in São Paulo, Brazil

“The street paper is my ganha pão, a Brazilian expression that means ‘with this job, I can live’.”

![Ocas" vendor Roberto Francisco dos Santos. [Credit: Luisa Santosa]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/INSP_Holiday-feature-2021_16.jpg)

Read part one here.