By Anna Mayr, zebra.

The oew (Organisation für Eine solidarische Welt) has been publishing the bilingual (German-Italian) street paper zebra. in the northernmost province of Italy for five years now. Nevertheless, the non-profit organization based in Brixen, South Tyrol, is currently distracted with concerns: the amendment to Italian law, commonly known as ‘Salvini’s law’, is having a negative impact on several vendors.

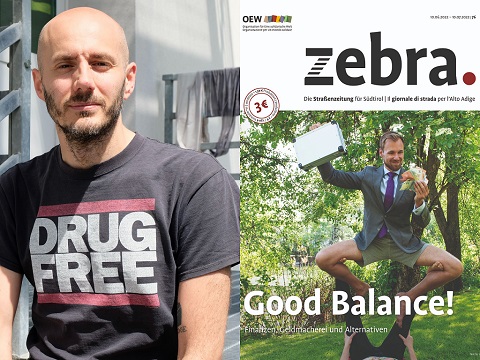

Eleven of the more than 60 zebra. vendors are directly affected by it. One of them is Geoffrey Onudu. In 2011, the 35-year-old fled across the Mediterranean to Italy, where he received the protection status of “humanitarian asylum”. He worked for two years in an agricultural company in South Tyrol, but has not yet found a permanent job, and makes his living by selling the street paper. The new law puts him in a rather hopeless situation.

The controversial amendment, that was made to the asylum law in December 2018, abolished the “humanitarian” protection status for asylum seekers in Italy. This status was previously granted to asylum seekers who did not fulfil the classic asylum requirements, but for whom expulsion also seemed unreasonable due to their personal situation. If Geoffrey is unable to prove that he has an employment contract, or a minimum income as an independent contractor, before his humanitarian asylum status expires, he will no longer be able to convert his residence permit into a work visa and remain in Italy. Instead, in all likelihood, he will have to leave the country. However, returns to the country of origin are hardly ever carried out in Italy. It is much more likely that the “rejected” will end up on the streets without papers or the right to stay. “I have been in Italy for eight years, I have learned the language, I pay rent and I want to contribute to this society. If they deport me now, everything will have been for nothing,” says the zebra. vendor resignedly.

“I have been in Italy for eight years, I have learned the language, I pay rent and I want to contribute to this society. If they deport me now, everything will have been for nothing”

Alessio Giordano, who works for the oew as a street worker and who is in constant contact with the vendors, explains: “Salvini’s law aims to exclude the weakest members of our society. This is in contrast to the values we stand for as the street paper zebra.” The written agreement with the oew, which can only register its vendors within the social project of zebra. but not officially employ them, is not sufficient for a work visa.

The lawyer Anna Bilello in Bozen, who has acted as an advisor for zebra. vendors in the past, adds: “The new law is very vague and creates more problems than solutions. It is neither a preventive measure to curb migration nor a measure to improve the asylum system in Italy.” All those who, in the past, received humanitarian asylum status in Italy would have received it from a legally binding Italian commission that considered it as necessary and justified.

The case of Geoffrey Onudu and his ten colleagues shows how Matteo Salvini’s new law further marginalizes those people in Italy who are already on the margins of society. Despite the amendment to the law, editorial director Lisa Frei wants to look to the future with confidence. “During the annual meeting, we collected constructive ideas and the street paper project will definitely continue,” she says. In September, the oew will present the 50th issue of zebra.