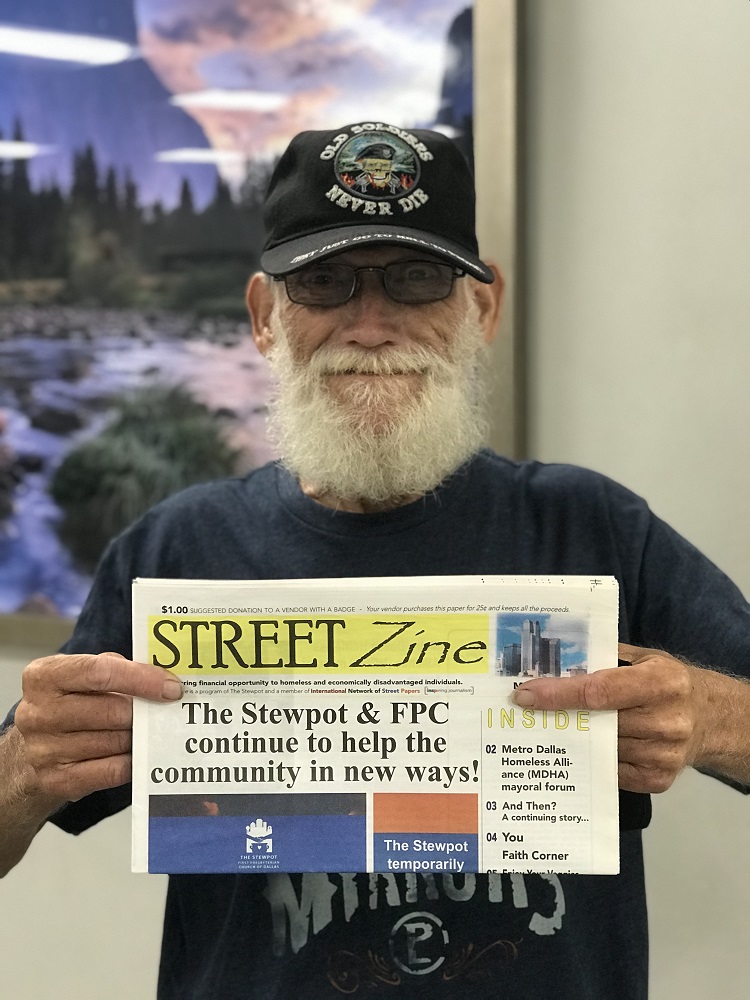

By Poppy Sundeen, STREETZine

For 16 years, Gary Keeton was a fixture in downtown Dallas, where he sold STREETZine. “I’ve been a vendor practically since the paper started,” he says. He was, in fact, one of the paper’s top sellers, using proceeds to help pay for lodging and necessities.

Then along came COVID-19. With in-person transactions between vendors and readers suddenly posing a health risk, The Stewpot [STREETZine’s publisher] halted street sales just before the April 2020 issue came out. That left Gary and his fellow vendors without the papers—and the proceeds they counted on.

“It’s been hard,” says Gary. “I’d really be suffering if it wasn’t for the First Presbyterian Church and The Stewpot. They get food to me and send me gift cards.”

Trying to fill the gap

The gift cards for vendors are funded by donations made on The Stewpot website where STREETZine currently resides in digital form. Gary spends the cards on food and occasionally on parts for repairing his bicycle. “It’s my major form of transportation,” Gary explains.

But while Gary is grateful for food and gift cards from The Stewpot, they aren’t a replacement for the income—or the job satisfaction—he received as a vendor. “I’m dedicated to that paper.”

A path back into society

Gary credits STREETZine with saving his life. When he first became a vendor, he was living on the street and battling drug addiction. “I think I would have been overdosed or dead if it hadn’t been for the paper.”

A STREETZine vendor profile featuring Gary caught the attention of the Veterans Administration. “The VA came and found me in tent city.” That’s how Gary, who had served eight years in Vietnam, gained access to benefits he deserved and sorely needed. “They got me into rehab and got me an apartment.”

A veteran, a father, a witness to history

Gary enlisted in 1969, at the height of the Vietnam War. “I was a squad leader. Served two tours. I’ve seen a lot of things that other people haven’t—some things no one would want to see.”

His return to Dallas was marred by episodes of PTSD. Gary became estranged from his family. Determined to make a life for himself, Gary built a career, married and fulfilled his dream of having a son.

When the marriage ended in divorce, Gary gained custody of son Clayton. “I had to leave him alone a lot to work.” Clayton left home at age 13. “After that, I just packed up my stuff and went to the parking lot across from the bus station to live on streets.”

Gary spent the next 15 years on the streets of downtown Dallas, not far from the spot where he stood on the day of the Kennedy assassination. “I was 12 years old, and I wanted to see JFK. He and Martin Luther King were my heroes.” He watched from a train trestle as the motorcade passed below.

It’s one of the many unique experiences that shaped Gary’s life. “I have enough stories for a whole lot of lifetimes.”

The cost of COVID-19

For someone as gregarious as Gary, isolation isn’t easy, and as a 70-year old with COPD, he’s at high risk for the virus. What’s more, his lung disease makes it hard to breathe when he wears a mask. “I put on a mask when I go into a store and get my shopping done as quickly as possible.”

It’s a far cry from the social life he had before the pandemic—spending time with fellow vendors and talking with his STREETZine customers.

“I’ve met so many interesting people,” he says. “I was selling papers near Dallas City Hall, so every month [then-Mayor] Laura Miller would come out and get the paper from me. I got to know the police chief and the downtown police. I got along with everybody.”

Loyal customers—and friends

Many of his customers have gone the extra mile to be helpful. “There was an executive who helped pay my rent for a year and people who gave me things I needed for my apartment. It was a godsend that they helped me out.”

Gary values the connection as much as the generosity. “That’s one of the reasons I work on the paper. I didn’t want to be outcast. And when you’re a homeless person, that’s what you are—an outcast. The paper helped me be a part of society.”

Everyone wants the pandemic to end. No one more than Gary. “I want to get back to being a vendor.”