By Hans-Albrecht Lusznat, BISS

A colleague once compared producing a documentary to building a house. Just imagine that you are all by yourself somewhere in nature, far away from any housing, without a supplier of materials and pre-made parts. You have one simple rule only: You are only allowed to use the materials that you have gathered yourself from your surroundings. Plastics, for example, are not allowed.

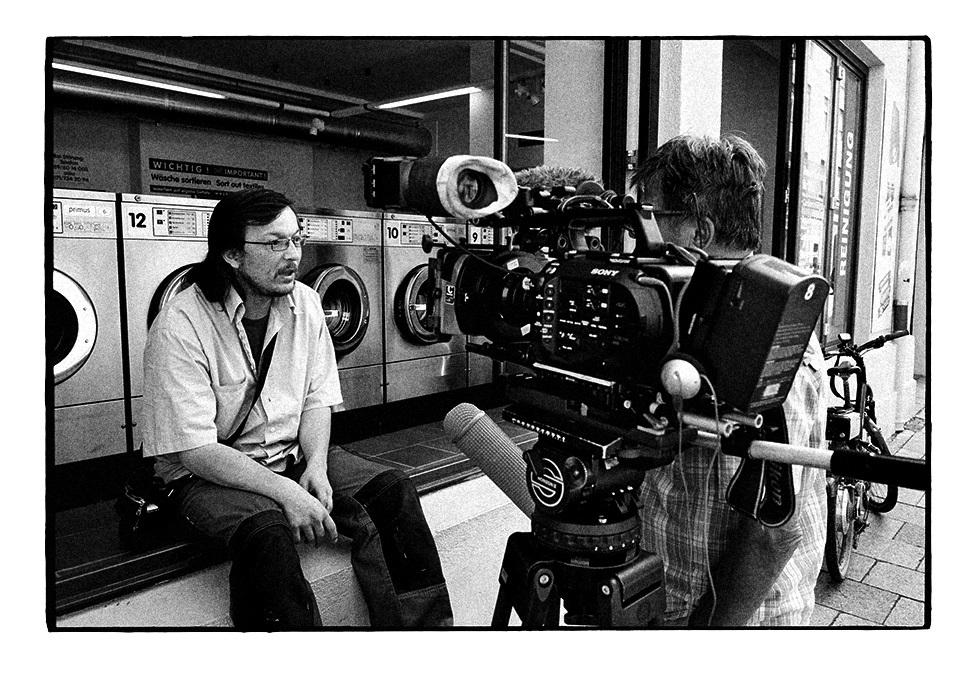

The production of a documentary is pretty similar. In our example, the director is the architect, who has something in mind regarding the purpose and the size of the building that needs to be approved by the homeowner. I, as a cameraman, am some kind of technical realisation manager who organizes the materials and stacks them in storage. The structural engineer, who builds the house from its different parts, is the equivalent of the editor.

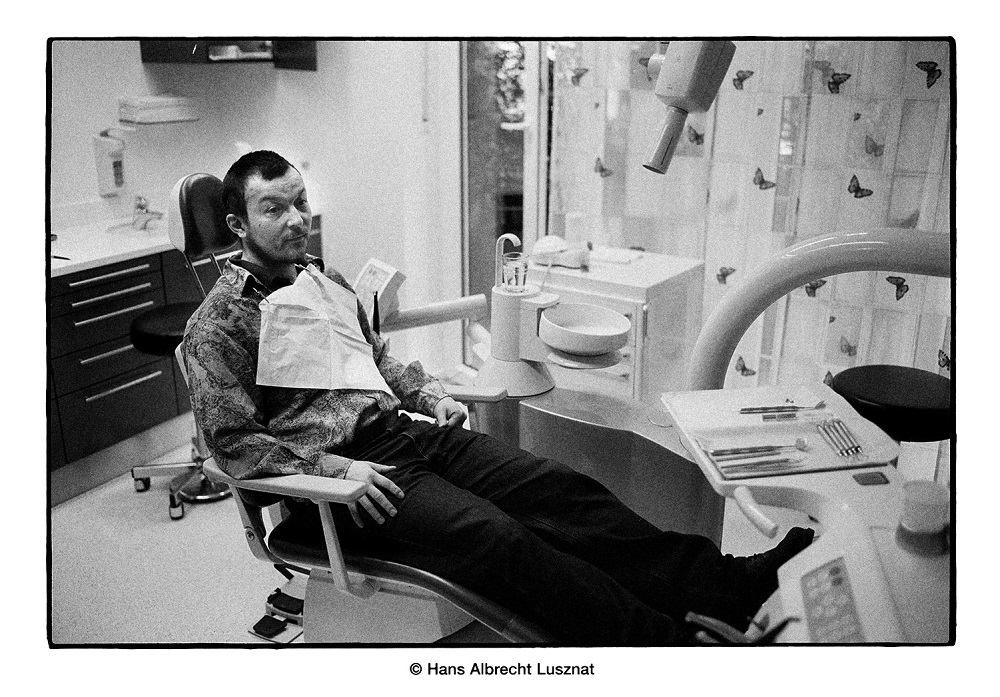

Movie making is never a slow process: it is always a head over heels rush and real-life doesn’t show any consideration for the process. For example, it is 26 May 2015 and Dalibor has a dentist appointment. As of late, Dalibor has been a permanently employed BISS vendor and his pitch is in the central station, in the mezzanine connecting the underground with commuter trains. Thousands of people pass by on their daily journey from the suburbs to the city of Munich. Dalibor is well organized, with his trolley and his plastic folding chair. He places his stack of BISS magazines on the trolley, propped up by its telescopic handle. We meet him in the district of Bogenhausen, as this is where there is a dentist who offers BISS vendors an excellent standard of care. Dalibor’s mouth looks like a battlefield: he previously neglected his teeth, which is pretty typical for people facing social difficulties. A difficult life often leaves marks on an individual’s teeth and those in the surrounding environment notice that fact, if only subconsciously. Successful people have bright white teeth.

Dalibor is one of four new BISS vendors that the film will accompany over the course of three years. The film is supposed to show the changes that permanent employment brings, while also providing some insights into the daily life of BISS vendors by capturing their needs and worries and documenting their attempts to get out of their current situation.

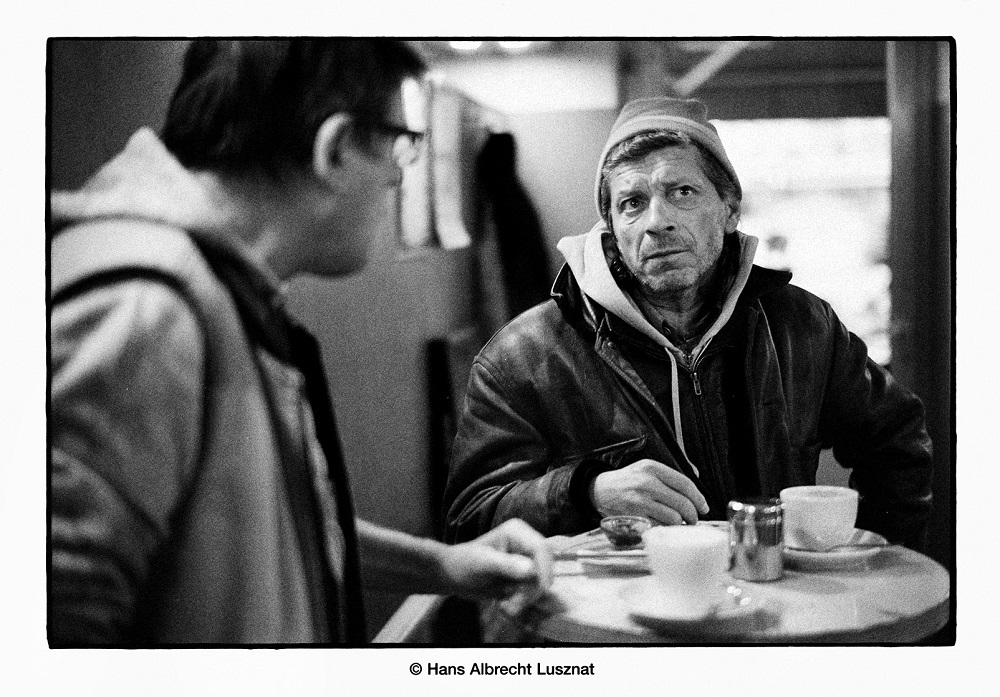

Dan travelled from Romania to Germany: he speaks broken German only and is difficult to understand. Germany seemed to offer great promise after the collapse of his marriage and after his small family – he has a son – broke down in his Romanian hometown. Dan used to sleep rough until a fellow countryman gave him the tip to join BISS. He is now a very successful vendor who has been selling more than 400 copies a month over the last couple of months. Although this volume of sales qualifies him for a permanent position, he is still living on the streets.

On Saturday morning, at 7am, on 19 September 2015, we are standing with our camera at the corner of Tal- and Westenriederstraße opposite the Isartor. Dan shows us where he sleeps, between the showcases of the arcades and the shop front of an optometrist. He needs some materials if he is to survive a September night outdoors unharmed: two layers of cardboard, a blanket and a sleeping bag at the very minimum. Now that it is morning, Dan packs up his belongings. He wants to be gone before 8am, as there is an unspoken agreement between the shop owners and the tenants. He packs his sleeping bag into the cart that he uses to lug his stuff around in the daytime. There is a thick stick taken from one of the surrounding trees placed under his blanket: the homeless people in the city are never safe from aggression. Dan hides the cardboard somewhere nearby, then grabs his cart and his bags and takes off for his pitch at the Münchener Freiheit, where the Oktoberfest-innkeepers start their festival procession through the city.

Dan speaks broken German and so our conversation moves slowly, in fragments. Wolle, the director from Berlin Neukölln, who usually has a quick tongue, struggles. How are you supposed to discuss the struggles of daily life on the streets in depth when you have so many difficulties in understanding each other? It is impossible. Should the film’s sequences be subtitled, with Dan talking in Romanian and with the help of a translator? The question remains unsolved for the moment, but Dan continues to participate in the weekly language classes that BISS offers to non-German speakers. Dan’s group of friends are all Romanian and, nice as it is to have a piece of home in the foreign country, this doesn’t make it easier for him to learn the language of his new home country. Although Dan and his friends speak Romanian with each other, we do notice that the communication between us improves from one meeting to the next.

Zuheir has language problems too. He is from Bagdad and lost his right hand in the second Gulf War in Kuwait. In Iraq, he was a member of the middle class. He managed to escape to Germany before the beginning of the refugee crisis. Without his right hand, he has no opportunity to work as a mechanic, which was his profession. Since he started selling BISS, Zuheir has started to feel good again and his open-minded approach to life has made him successful in the role.

Unfortunately, Zuheir also lacks language skills. Learning German is vital for him, as he has to pass a language test if he is to get a German passport. He has failed the test three times, but Zuheir won’t give up. He attends German classes for foreigners at a community college in the city centre where a Chinese teacher teaches the class, which is proof of the fact that it’s possible to master the language. Zuheir’s usual pitch is in the mezzanine of the commuter train station Rosenheimer Platz, although he sometimes sells the magazine on the go.

Andrea is another protagonist in our film. An unfortunate series of events made her slip into poverty, but she now has a small apartment between Ramersdorf und Perlach. She started selling BISS magazine as a freelancer and she is highly motivated. Her pitches are in the underground stations at Poccistraße and Goetheplatz. She also sells the 400 copies per month that are the pre-requisite for permanent employment. In August 2015, while we are sitting in the BISS sales office with our camera, we watch as Andrea receives her work contract from Johannes Denninger. Our society still regards a job as being the main key to participate in life in society: a person who has nothing can’t get anywhere without a job.

Some people make a fortune out of your poor fellow citizens. You only need a more or less run-down building that you can divide into single rooms, equip it with bunk beds and wardrobes and put a poster up on the front: residential hostel, 100 euros a week, 400 euros a month. Dalibor lives in one of these hostels, where he shares a room with two others that he can only reach by going through a walk-through-room that is home to two people. It costs 1,200 euros for a room that is roughly 16 square metres, which means a gross of up to a few thousand euros per month for the entire building. The room that Dalibor lives in is sparse – it reminds me of a room in a military barracks – and it has a basin, three wardrobes, a table and three chairs. One of the roommates has a TV. Dalibor has been living in these circumstances for three years, but permanent employment with BISS has opened up new opportunities for him. He will soon get his own small apartment in the north of Munich from the Wogeno eG, a new housing cooperative, which was approved by the Department of Housing and Immigration. In November 2015, Dalibor gets the keys and visits his new place close to the Frankfurter Ring for the first time.

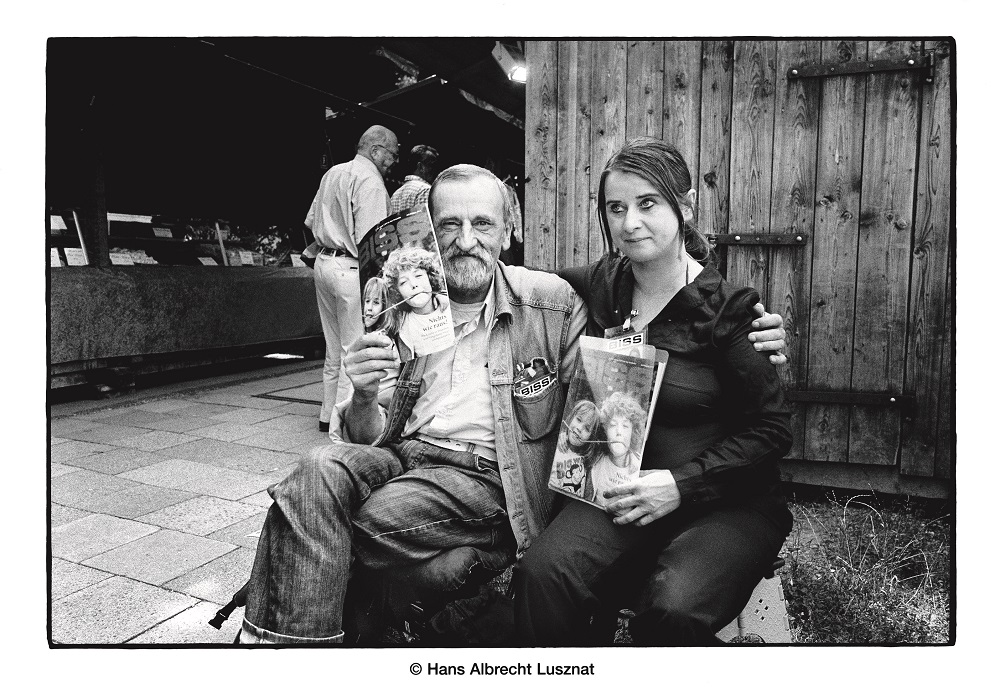

Close connections also come to exist among those selling the magazine: many vendors are not all by themselves when standing at their pitches. We meet Andrea and Heinz at the Auer Dult. Heinz is an old hand and has been selling the magazine for years. He says that Andrea is doing well: she engages her customers in a conversation and enjoys her work.

The first year of filming comes to an end. Director Wolfgang Ettlich and I have collected many gigabytes of material for our film. Let’s return to the opening image of this article; the construction of the house. So far, we have collected lots of material and stacked bricks, but we still cannot tell how the single parts will connect in order to make a single whole. So far, we feel that our idea of the film and the things happening in front of the camera in reality are starting to come together, but we still don’t know where our path will lead us.

The new year starts pleasantly, at least for Dan. It is extremely cold outside. That’s why he moves into a sleeping hall at the Bavaria Casern every evening. In the morning, he has to pack up his trolley and his bags and leave again. He suffers from headaches. In March, everything gets worse. Dan suffers a brain aneurysm and has to undergo surgery at the Pasinger Hospital. One thing becomes obvious: without BISS and his permanent job with the magazine, he would probably not have survived the winter. 50 per cent of people with a burst blood vessel die. But Dan was lucky. As a result of his medical situation, the Department of Housing and Immigration organises a room in a guesthouse for him. The room is only as wide as the mattress on the floor and there is just enough space in front of it to open the door. A small fridge stands in an alcove, there is a chair, some space to put his things, and that’s it. I kneel with a wide-angle lens on the camera in front of the mattress and try to get a panning shot from the fridge over Dan, who is lying on the mattress, to the chair and, finally, to the hanger on the back of the door. This shot captures the 8 square metres room that I had to sneak into by avoiding the communal kitchen so that the landlord didn’t notice me. He is sitting in the kitchen, watching everything like a hawk. Dan is happy about his tiny new home and is scared of losing this permanent place that he can call his own. In the basement, people from different countries are living in drywall-installation shacks, where they crouch over open cans at dinnertime. You could film quite unbearable images here! But nobody wants that: not those sitting there and certainly not those responsible for it.

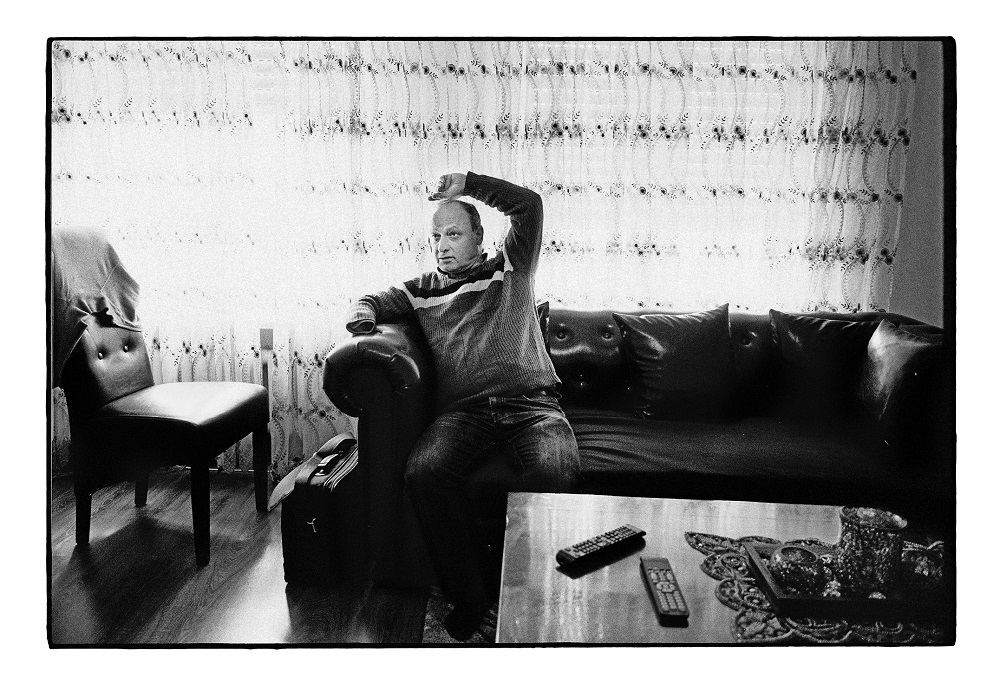

We go to meet Zuheir and we are allowed to film inside his apartment. His wife is working, and she doesn’t want to be filmed. Their living room is beautifully furnished with a lounge suite, table, chairs and a big flat screen TV. He is content. We can understand why when we hear some of the news from Iraq. Zuheir is still learning German for his language test. BISS has helped him to get an electric tricycle with a lockable box on top of the back axle and the Dynamo Bicycle Workshop has adapted a standard model to meet his needs. With only one hand, he is less flexible than the average Munich cyclist and the tricycle helps him enormously.

Dalibor has also moved into his own place and has furnished his one bedroom-kitchen-bath flat nicely. This successful phase that he finds himself in has been threatened by the pain that he experienced when walking: as a result, he is selling fewer copies of the magazine and is becoming frustrated.

There has been a lot of talk in the media about the relationships between movie producers and their protagonists, which range from clichés to accusations of slave-driving. These critics are right when it comes to many TV formats, especially when it comes to pay TV, as these productions are often a demanding process that often have a cynical way of dealing with people in front of the camera. In my opinion, documentary filming is different to this: it is a process of paying the maximum amount of attention, which is accompanied by a certain kind of affection for the protagonists and an understanding of their opinions, even if they don’t match your own. Us documentary filmmakers give the subjects of our films our undivided attention and gain real insights about their lives. Filming often reminds me of therapy: the camera lens looks unflinchingly at reality, underlining the sincerity of the moment and recording something that the protagonists want to preserve.

The third year of filming begins. Dalibor left BISS after he didn’t manage to sell the 400 copies a month necessary to remain an employee. If he manages to find another adequate job and keep his apartment, one cannot call that a failure; instead, it’s a story of the success that can come of being employed by BISS. Andrea has become more confident, has changed her appearance step by step and has found her own place. Zuheir is as active as ever; he is flexible thanks to his tricycle and is constantly on the move. Given his zest for life, it is just a question of time as to when he will hold the German passport in his left hand. Dan also still has his dream. He wants to bring his son to Germany and improve his living conditions. In order to achieve this, he is constantly found standing at his pitch at the Münchener Freiheit, or at the Englischen Garten if the weather is nice. Going back to Romania is not an option–that possibility is not even one that he will consider.

Johannes Denninger is head of sales at BISS. He signs work contracts and takes care of the organisation’s employees. Originally, he was a social worker and the skills that he learned in that line of work are exactly what is often needed in his role. What’s needed is a distanced but firm intervention when things go wrong, a certain type of optimism and a portion of indifference if you don’t want to go mad in the face of adversity. He now has 20 years of experience, during which time almost 1,000 vendors have worked for BISS. Many have left or died, while others remain among the 100 or so vendors that are employed at any one time. Johannes knows the difficulties that vendors face and can comment on many things and put them into perspective. BISS Director Wolfgang Ettlich has also built up his experience of helping vendors over the years.

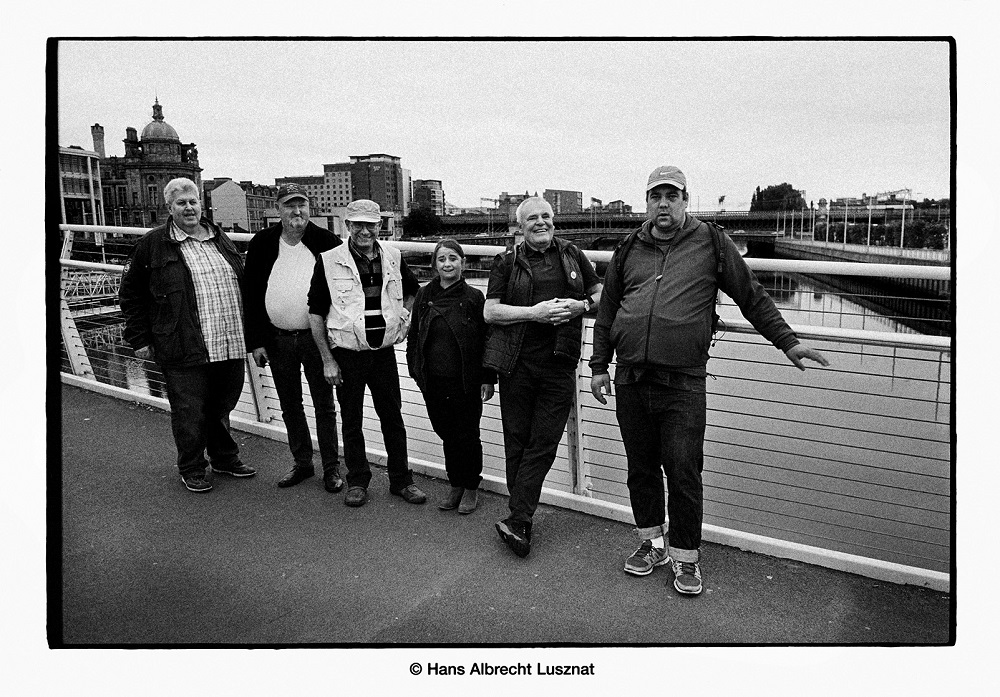

In the film, we often use Johannes’s statements to link important aspects within the context of the movie. One key phrase delighted me; namely, “social space exploration”. Why did we travel with five successful BISS vendors to the Homeless World Cup in Glasgow? We went along because Andrea was one of the five BISS vendors who took part. She was tense as soon as we got into the plane and she clung to the armrest during take-off. Andrea had never flown before. Many of the less fortunate in our society miss out on such opportunities and experiences. In addition to not being able to afford to fly, BISS vendors also can’t afford to eat out somewhere nice. In Glasgow, over a dinner eaten among friends, they learn how these social interactions work, such as learning how to order, which glass to use for which drink and how to use the various types of cutlery next to their plate. This kind of learning happens easily, through the course of mutual conversation and interactions, and when we leave the restaurant, everyone has had a great experience.

Let’s return back to the starting point of this article for one last time. After three years of filming, the construction side of things is now packed with materials that we have gathered from our surroundings. Now the time has come to start the actual construction process. Our editor, Monika Abspacher, gets an overview of the material and starts to assemble the sequences. It becomes clear that the story is guided by the passing of time and that the documentary should focus on the experiences of the four protagonists. Ultimately, we want to see the improvements in their lives over the course of the film.

A film is a complex thing. Once it’s finished, you think that the finished film will be the same every time that you screen it. After all, it’s a sequence of digital data that doesn’t change in itself: it remains the same, with its volume of 4,000 million bites. At least, this is how our film is, in digital terms. However, despite this, the film changes every single time it is screened: it might seem too long or too short, to serious or too humorous, both because the audience changes and because the audience changes the movie when they watch it. It sounds strange, but it is the truth. I have participated in many film tours and I’ve seen it for myself: every evening, the same movie reel is placed into the projector and every evening, a different film is shown, thanks to the impact that it has on the audience.

Translated from German by Jessica Michaels

Watch the BISS documentary below