Declining interest and sales in print media; fundraising concerns; difficulty adapting to changes in journalism and society; ever increasing poverty and homelessness; soaring housing prices; scarcity of housing and social benefits; displacement of entire communities – these are all factors that could lead to the shuttering of a street paper. And yet, such closures are few and far between. Street papers are instead rising to the challenge, meeting these obstacles head on, and innovating to overcome them.

Last month, INSP received an email from Bergen street paper Megafon:

“From 31 December 2019, Norwegian street paper Megafon will be no more.”

It calmly went on: “There’s nothing dramatic behind this decision; quite the opposite. Since 2014, we have seen a decline in vendors, as fewer people have had to rely on their vendor jobs to survive. Our local government has made an extra effort over the last five years to improve the living conditions for our vendors and other marginalised groups.”

At the 2019 Global Street Paper Summit, and in interviews with INSP in September, several street paper staff expressed conflicting emotions at the continued existence of street papers. The fact that almost 100 street papers are still going strong throughout the world is evidence of these organisations’ perseverance and successful ability to overcome difficulties to their work. But it also shows that homelessness and poverty are still unaddressed global problems. If those issues didn’t exist, then neither would street papers. There is the sentiment that the ultimate goal of a street paper is to put itself out of business – to have worked so effectively at helping those marginalised by society that the street paper can shut up shop.

The end of Bergen’s Megafon suggested that its closure wasn’t bad news at all, but rather that it had succeeded in this goal.

On this, in a Facebook post, the staff behind Megafon wrote: “The goal has always been the same: to make ourselves redundant. Now, thanks to both you readers and a formidable municipal effort, we have arrived.”

The email INSP received went on to cite improved housing projects, drug treatment and welfare services as reasons why the socially and economically disadvantaged population of Bergen no longer needed Megafon. Out of nearly 900 registered vendors, by October 2019 it had only eight left active.

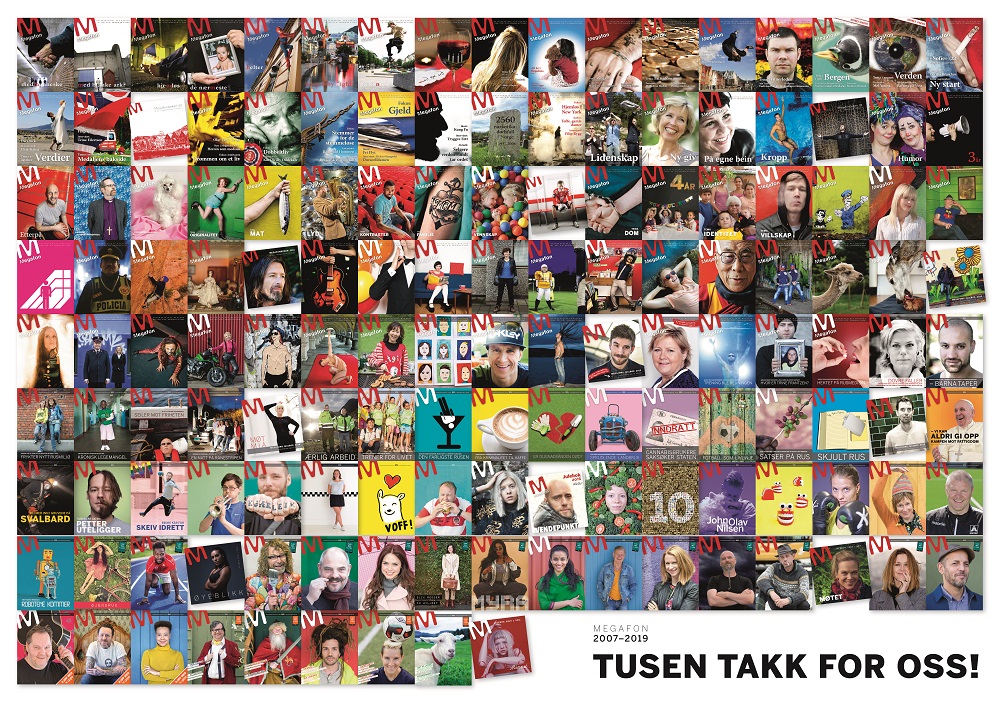

In its time, Megafon – which has been overseen by the Centre for Workplace Preparation (ALF) in Bergen, an organisation which offers low threshold services to drug users and people who otherwise find themselves outside ordinary working life – published 133 magazines and 11 special editions.

INSP contacted Megafon’s soon-to-be former editor Petter Lønningen, who has been working in street papers for almost 13 years, to shed some more light on the reasons behind the end of the street paper.

“Norway is different from other places with street papers – we don’t really have a homelessness crisis in the same way other countries do,” said Lønningen. “So Norwegian street papers are different. You rarely see people sleeping on the streets here. Instead, our vendors have an addiction, most often to opiates and amphetamines. We do have a problem with relative poverty, but that can’t be compared to poverty you find in many places across the rest of Europe or the US.”

The local authorities in Bergen have implemented forward-thinking policies when it comes to treating drug addiction, including medical support, substitution drugs and other harm reduction services, and matched them with more basic facilities, like access to free hot meals, in order to help those who want to get clean, and at least manage those who don’t.

It may seem basic but, most crucially, Bergen has been focusing on rehabilitation. When so many local governments turn quickly to the criminalisation of those with addiction issues, it is a quietly radical approach.

“As most people with an addiction will tell you, it’s not the quitting that’s difficult – people do it over and over again,” said Lønningen. “The problem is to stay clean afterwards, and to do that, you need something to keep yourself occupied, something that you can use as a foundation for a new identity. That’s why an important part of the rehabilitation program is everyday activities such as band practices, photography courses, meditation, arts and crafts, horseback riding, camping – all this in addition to health services and housing. This is actually crucial for staying off drugs. Of course social benefits have increased over the last few years too.”

Perhaps the most important of all of these though has been substitution treatment, mainly administered through methadone, but also through other substitute opioids like Subutex and Suboxone.

“When Megafon started in 2007, most people with an addiction would need around 1500 Norwegian kroner [approximately 148 euros] a day to support their heroin addiction,” explained Lønningen. “Around 2013, local health services decided that it should be easier to get methadone. This turned out to be a success, and today the heroin market is almost gone. There’s a new drug reform around the corner that opens up for heroin prescriptions, which will probably undercut the illegal opioid market completely.

“Then there’s Naltrexone, an incredibly promising medication that removes cravings [and the effect of] opioids. We’ve met so many people who had their lives completely changed over just a few years.”

This had great consequences for Megafon. “Most of our vendors no longer need the income they once got from selling magazines. They are getting treatment for their addiction, and can fill their spare time with other work and activities. There’s still a need for more work related activities, but that’s next on the local government’s list. There are already several possibilities for those who would like to work, and more is on the way.

“So Bergen is doing things differently from other cities – even in Norway. But we’ll probably see more [of these progressive local government policies] implemented in other Norwegian cities in the years to come.”

Across Europe, the refugee crisis has meant the arrival in many major cities of people in need, and with little help from local authorities due to their status, migrants have been finding a leg up in street papers, keeping vendor numbers, at the very least, steady.

In Norway, the situation is murkier. “There’s actually been a reduction in the number of refugees coming here,” said Lønningen. “This is mostly because of strict immigration and asylum policies. There’s broad parliamentary support for these policies, making Norway less attractive for asylum seekers. In 2015, during the peak of the refugee crisis, Sweden accepted around 160,000 asylum seekers; Norway took in just 30,000.”

So while a relative lack of refugees means less requirement for Megafon (Bergen does have a small population of refugees, according to Lønningen, but they do not see the street paper is a viable income source for their needs), it isn’t necessarily due to similar broadly progressive policies as those addressing drug addiction in Bergen. But, Lønningen says, there are other factors. Namely, cash is almost obsolete in Norway, making it a more difficult place for migrants and traveller communities to transition towards, especially outside the capital of Oslo.

![Previous Megafon vendors Geir Arne Olsen, Wibecke Lill Olsen and Wolfgang Ahlheit. [Credit: Irene R. Mjelde]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/collage.jpg)

Despite now having to move on from Megafon, Lønningen still firmly believes in the necessary existence of street papers and the movement. “During [my time working in street papers], I’ve seen so many changes for the better,” he said. “Not just for our vendors, but in how the mainstream media treats issues such as addiction, gentrification, and poverty. Before street papers appeared in Norway, you’d rarely see interviews with people struggling with addiction. Now, it’s much more common.

“To me, street papers are first and foremost an opportunity to earn their own money in a legal and dignified way, and thus, to be independent. I’ve met young girls and boys who earlier had to turn to prostitution in order to get the money they needed, and parents who had to get a third job just to be able to pay off their children’s drug debts. But street papers have also given many different people a voice that otherwise wouldn’t have been heard, which in turn has changed people’s perceptions of them as a group.

“But there’s still much to be done. Street papers should strive to battle prejudices even more.”

Going forward, collaboration between the remaining Norwegian street papers is key, says Lønningen. =Oslo will be picking up the slack in Bergen, offering the few remaining vendors the opportunity to sell its more nationally relevant title =Norge, supporting them through the transition.

Highlighting this, Megafon’s final issue will be its annual Christmas edition, a collaboration with =Oslo and Trondheim’s Sorgenfri.