By Ann-Derrick Gaillot

When I ask Vicky Tauli-Corpuz how she got started in organizing and activism, she takes me back to the Philippines in the 1970s. The World Bank, at the request of dictator Ferdinand Marcos, was funding a dam project on the Chico River in the Cordillera region. North of Manila, the region has been home to and protected by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years, including Vicky’s people the Kankanaey Igorot. Building with no input from or notice given to nearby Indigenous communities, the dam project threatened to destroy their sacred lands, their culture, and displace thousands of Indigenous people.

Seeing the impending destruction, Tauli-Corpuz, already involved in anti-dictatorship and anti-Vietnam War efforts while a student in Manila, organized with other Indigenous students. Soon, the Indigenous peoples of the Cordillera were united in resistance efforts against the project. Despite violent retaliation from the Marcos dictatorship, their opposition forced the World Bank and government to abandon the Chico River dam project. “We have our own traditional systems where people come together to talk about the issues that are affecting them, and then to think of plans of action,” she remembers. “These are very traditional systems that our ancestors and elders have been doing. And that’s how we decided that one way for us to fight the dictatorship is to organize ourselves and organize the communities where we come from, and that’s how we learned. It’s really learning by doing.” From then on, Tauli-Corpuz continued organizing and creating networks between Indigenous peoples in the Philippines.

By the early 1980s, Tauli-Corpuz began working with the United Nations to set up a framework for protecting Indigenous rights globally. The result was the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007. Seven years later, Tauli-Corpuz was appointed the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In charge of meeting with Indigenous leaders all over the world, she reported on the human rights abuses Indigenous peoples face as they fight to protect their lands as well as their successes in asserting their sovereignty and protecting biodiversity.

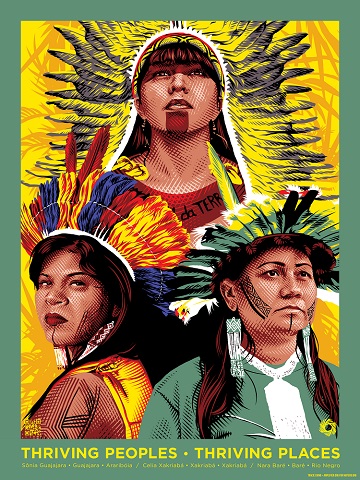

Today, Tauli-Corpuz juggles many roles as she continues to struggle for Indigenous sovereignty and environmental conservation the world over. One of those is as a member of the board of directors of Nia Tero, a Seattle-based non-profit focused on securing Indigenous guardianship of vital ecosystems. She is also one of nine Indigenous leaders honored in the organization’s ‘Thriving Peoples. Thriving Places.’ campaign, in association with non-profit design lab Amplifier.

Tauli-Corpuz spoke to INSP from Baguio, a city in the mountains of the Philippines’ Cordillera region, about Indigenous sovereignty, environmental conservation, and what gives her hope as the struggle continues.

INSP: What changes have you seen over the past few decades as far as how Indigenous people are shaping global dialogue on conservation and fighting climate change?

Vicky Tauli-Corpuz: Indigenous peoples came together precisely because of similar problems that we all face in terms of states violating our rights to control and having a say over how our lands and territories are being used. That’s what brought us to the United Nations to work for the drafting of a UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [beginning in 1985]. The whole period was a period where we decided that the international community can indeed have the capacity to influence decisions of states to be more respectful of human rights.

So we did that. We linked up with the UN Commission on Human Rights. Even before we got the Declaration, [we] said we would like to be involved in ‘92 when the Rio Earth Summit happened. I was there and several Indigenous peoples were there. And we tried to influence the convention on biological diversity to put paragraphs [in the resulting documents] that will recognize our rights and our contributions to biodiversity. So we, and when I say “we” that’s Indigenous leaders who were involved in this process, thought it will be better if we are engaged actively in the convention [and that they] respect Indigenous peoples when they try to meet the goals of the convention. And that’s how we engage.

The impact is that there are now active Indigenous caucuses: the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Biodiversity, which is involved directly in engaging with the convention. There is also one in the climate change arena. And those of us who had the possibility of becoming members of the government delegations, we also agreed to become part of the delegations so that we are there directly shaping and making the language that we think is relevant for us. [For example], I became a member of the government delegation for the climate change convention when the REDD+ discussions were happening about reducing emissions from deforestation.

Now there are several decisions that have come up from these conventions which say that the rights of Indigenous people should be protected, their traditional knowledge on how to conserve biodiversity and protect biodiversity should be enhanced further and recognized, and direct participation of Indigenous peoples in making decisions and policies at the national level should also be encouraged and in the implementation of these programs and actions at the national and the local levels.

So I think that’s the impact. At least the participation of Indigenous peoples is there. But of course, the implementation is still a big question mark. You have to struggle still at national levels to make sure that Indigenous peoples are involved, to get them invited when these discussions are happening, [to make sure] the work that Indigenous peoples are doing (which they have been traditionally doing) is also recognized and support is provided in terms of recognizing the rights to their lands and territories, in terms of resources, as well as technologies. So that’s basically, I think, where we are.

Can you speak more to the connection between conservation and Indigenous sovereignty? How do you explain the importance of that connection to people who want to support conservation but don’t consider Indigenous sovereignty?

I think that the way to explain that is to really show the evidence. The World Bank came up with a report which says while Indigenous peoples occupied 22 per cent of the world’s territories, 80 per cent of the world’s biodiversity are found in these territories. So that’s one fact that has already been established by scientists and acknowledged now in several reports that we see.

[Another] one is showing that in many of these communities, Indigenous governance systems are in place. [Places recognizing] the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples to self-govern and to determine their economic, social and cultural development are the places where you can also see this kind of a reality.

As Special Rapporteur, I went to Mexico and Ecuador. The people who have these autonomous municipalities came to talk to me, and they told me that they have marked their communities and they can show to the government that it’s their communities which have the highest levels of biological diversity. But it’s because they are able to govern in their own states and municipalities. These people from Mexico came to me and they told me that it’s their autonomous government, their sovereignty, that ensured that this biodiversity and the forest are still kept in a better shape compared to other territories. Even in Brazil, for instance, there’s this famous Xingu National Park. Actually, the territories of Indigenous peoples where they live which are not part of the Xingu National Park are better kept. They have higher levels of biodiversity. There’s very little deforestation happening. So, I think that’s the way to link sovereignty with biodiversity protection and conservation.

“You have to struggle still at national levels to make sure that Indigenous peoples are involved.”

And that’s why I always tell the IUCN [International Union for Conservation of Nature] people, why don’t you document all of that? You have all the possibilities to document these realities, but it is us Indigenous peoples, we have to be the ones who will do the documentation. We have to beg some academic institutions to help document this. But if we are able to work together to [create] all the reports about this, then it will really enrich the evidence that is needed to convince other people to support the demands of Indigenous peoples to have their rights over their lands and territories and the right to sovereignty to have rights respected by states and by corporations as well.

What was one concern you came away with from your time as the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples?

The overarching concern for me is really the non-implementation of the UN Declaration of Indigenous Peoples, which means the recognition of Indigenous peoples to their territories are not happening in the way that we would like to happen. Titles are not provided, no demarcation is happening. And even in countries where demarcation has happened, in Brazil, for instance, the Bolsanaro government totally disregarded many of these because they came up with a law which says those who haven’t delineated their lands before 1989, before the constitution was created, cannot have a claim over their territories anymore. So there are many legal steps being taken by states to undermine the implementation of and the protection of the rights of Indigenous peoples to their lands and territories. And those who try to fight to protect these rights and to fight against their displacement, against the entry of destructive government projects, they are the ones who are arrested and put in jail.

So while our governments have signed onto these conventions and even the declarations which protect the rights of Indigenous peoples, it’s really an uphill battle all the time. It’s only when Indigenous Peoples are strongly organized, they are empowered, that they manage to get some gains. But the governments will not go out of their way to do it. And then, because the last remaining [natural] resources in the world today are found in Indigenous territories because they have protected these lands, those resources are magnets for corporations to collude with governments to take over these resources and lands.

That’s why [Indigenous leaders] are also linking hands with allied organizations, institutions who understand this problem. It really takes a concerted effort not just from Indigenous peoples, but from human rights defenders, from people who simply believe that Indigenous people should be allowed to continue living in the way that they would like to in protecting the territories that they live in. That’s the kind of effort that I’m trying to do now, trying to reach out to academic institutions, to NGOs, civil society [organizations], other social movements, so that we’ll be able to really forge our strength and get the states and the corporations to respect and protect the rights of Indigenous people.

![Vicky Tauli Corpuz — Kankanaey Igorot – Besao; Filipino activist and development consultant. [Designed by Tracie Ching, courtesy of Nia Tero / Amplifier]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/INSP_Nia-Tero_Amplifier_Indigenous-women-poster-campaign_6.jpg)

What would you say to people, especially young people, who are getting the impression from media coverage and social media that it’s too late to meaningfully combat climate change, or basically that we’re doomed?

I think that you have to give hope, and the way that we give them hope is by showing communities are able to survive and adapt to these changes precisely because they are working together. They are conscious about how their actions will have an impact, not just now, but on the future. It’s important to show the young people that things can be changed. I think that if we are just resigned to the doom and gloom, that’s that. But our role, especially as elders, is to give the young people hope that if they are able to continue these practices, use the technologies, use the knowledge, the sciences…that will allow us to survive, but at the same time to recover and restore the ecosystem to what we would like it to be.

That’s why the interlinkages between the young people and the elders, and of course the role of Indigenous women and women in general, [is important] in terms of promoting these values of nurturing, compassion, empathy. All these values have to really be taught to the young people so that they will not think that they are really in very bad shape. They are in deep, but I don’t believe that it’s hopeless. We’ve lived over how many thousands of years, and we will be able to do it.

And I think bringing them to communities who are doing whatever they can is also inspiring. I remember as a young activist, we visited many communities. And that’s where I learned that as long as the community is intact and they really have a collective view of what they would like to be, things will be moving in the ways that they would like. These kinds of immersion activities, where the young people are brought to dialogue [with] the older ones and come up together with some common plans. It’s what we need to do, because we cannot afford to lose young people. Many of these people are very intelligent. They should use that intelligence to really do what matters.

What are the resistance movements people can look to for guidance or encouragement now?

In the US, of course, we have the resistance against the oil pipelines, for instance, in the Dakotas. I think that’s a good example to see [because the pipeline] was stopped. It’s the same in Canada. In our communities here in the Philippines, we managed to stop some mining companies from coming into our territories. We fought for a national law on Indigenous peoples’ rights that says that the free prior informed consent of Indigenous peoples has to be paid whenever any projects are brought into their territories. And in Latin America, the Indigenous municipalities that are autonomous, you can see what they did. This Purepecha village in Michoacan, in Mexico, it was the women who really started the fight against their forest being destroyed by the drug cartels. They joined their hands together, they put up barricades, and then they started to stop the logging trucks from coming in. And the men, of course, eventually joined them. The government joined them. They kicked out the corrupt government officials who were the ones in power and colluding with these drug cartels.

In Colombia, you can see this with some of the autonomous municipalities as well. They have protected their territories. They insisted that they run their own schools. And so they are the ones teaching the young people before they go to the university in Bogota. And I’ve met young people who are very bright. The children of one of the Indigenous leaders [in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta] — one is an astrophysicist, one is an ethnobiologist — and they finished [school], but they went back home and they started to do work in their own territories. I was so inspired by that.

So there are really very many examples of Indigenous peoples trying to assert their rights and showing good results for it. And if we are able to really talk more about that, show those kinds of good examples, then I think that people will rethink and will be more concerned in how to build stronger communities. At the end of the day, that’s really what we’re looking for. Stronger communities who are united, who are able to assert their rights and who are able to build their own capacities to run their own governments and their own justice systems and education systems. And if they are able to do that, then why should the government penalize them for doing that? In fact, I was telling them at the Mexican government, you should be very thankful that even without much resources, they set up their own system. They have their own Indigenous guards, which protect the security of the community, and they do not even receive any salaries from you. So these are examples of the kind of empowerment that we should encourage communities to do, and not just to be leaving it to Indigenous peoples. Because I think that really can happen in whatever community that is.

Ann-Derrick Gaillot is a freelance journalist and writer based in Missoula, Montana. Find more of her work at annderrickgaillot.contently.com.

INSP members can download this Q&A for republication from the INSP News Service here.