By Israel Bayer

Diane Yentel is the President and CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, a membership organization dedicated solely to achieving socially just public policy that ensures people with the lowest incomes in the United States have affordable and decent homes. She is one of America’s leading voices on housing and homelessness.

A veteran housing policy expert, Yentel’s footprint can be found in every part of the country. From advocating for low-income renters by testifying in front of Congress, to educating the wider public on how to support a broader housing justice movement on major TV news outlets and on social media, Yentel and her organization’s work is a force of nature.

INSP talked to Yentel about the eviction and housing crisis in America, what’s at stake in the upcoming Presidential election, the intersection of racial and climate justice with housing, and what readers can do about it.

Israel Bayer: Tens of millions of Americans now find themselves facing both a public health and housing crisis. Can you paint us a picture of how we got here, what’s happening on the ground and what the answers are?

Diane Yentel: To understand the eviction crisis now, we have to recognize where we were before COVID-19 emerged in our country. We were already in the middle of a severe affordable housing crisis – where we have a shortage of seven million apartments affordable and available to the lowest income people. Another way of saying this is that for every 10 of the lowest income renters in the United States there are fewer than four affordable apartments available. As a result of this shortage we have 10 million very low-income households, or about 25 million people that are paying at least half of their income towards rent each month. Many are paying much more. In some cases, people are paying 60, 70, 80 per cent of their income just to have a roof over their heads. When people have a limited income to begin with, and you’re paying so much for a place to call home, you’re always one financial emergency away from missing rent and potentially being evicted and, even worse, becoming homeless.

For many of these same renters the coronavirus is that financial emergency. They’ve lost jobs, they’ve lost hours at work and they’ve lost wages. It’s harder than ever for people to cobble together enough money to pay the rent.

The recent national moratorium on evictions for nonpayment of rent is long overdue and badly needed. As we have said for five months, the very least the federal government ought to do is assure each of us that we won’t lose our homes in the middle of a global pandemic: the administration’s action would do so and will provide relief from the growing threat of eviction for millions of anxious families. The eviction moratorium is an essential step, but it’s still a half-measure that extends a financial cliff for renters to fall off of when the moratorium expires and back rent is owed. This action delays, but does not prevent, evictions. Congress and the White House must get back to work on negotiations to enact a COVID-19 relief bill with at least $100 billion in emergency rental assistance. Together with a national eviction moratorium, this assistance would keep renters stably housed and small landlords able to pay their bills and maintain their properties during the pandemic.

If Congress doesn’t act, as many as 30-40 million renters are still at-risk of losing their homes at the end of the year. The federal government must ensure that individuals and families aren’t going to lose their homes at anytime during a public health emergency.

“Housing justice and racial justice are deeply intertwined. They are two sides of the same coin. We can’t achieve one without the other.”

What’s at stake in the upcoming election in November?

The housing crisis can’t be solved without intervention at all levels of government. Many of us have asked for many years: what’s it going to take for policy makers to actually prioritize the needs of low-income renters?

When you look at the difference between who votes in elections it’s very obvious what it’s going to take. Higher income homeowners vote at a much higher rate than low-income renters. It’s a stark difference. It’s not enough to say I’m a constituent, or an advocate. Policy makers know who votes in their community and who doesn’t. That’s who they listen too, and that’s how they prioritize the policies they are going to advance. Until we change the equation of who votes we will never get policy makers to prioritize at the scale we need them to for solutions to end homelessness. Changing that equation changes everything.

There are a lot of reasons why low-income renters don’t vote at the same rate as higher income homeowners. Outright voter suppression, election day being on a workday and election sites in low-income communities oftentimes being understaffed all contribute to lower voter turnout for low-income renters. No one should have to face the loss of hours and wages to wait in a long line to vote.

There are structural changes that need to happen to our country’s voting system to actually make it possible for low-income renters and people experiencing homelessness to really participate in democracy. Still, there is a lot we can do now to get people to register and vote. We have to find a way to empower and enable low-income renters to register and show up to vote. We have to be seen as the powerful voting block we are to accomplish the change we seek.

“The very least the federal government ought to do is assure each of us that we won’t lose our homes in the middle of a global pandemic”

Knowing the country was already facing a housing and homelessness crisis prior to the pandemic, you become President of the United States in January 2021. What do you do, both practically in the short-term and systemically long-term, to support housing justice in America?

The most important and consequential thing a President can do to impact housing in our country is adequately staff the agencies responsible for overseeing housing systems in our country with people that care about low-income housing and renters. This administration has shown the consequences of when that doesn’t happen. When you have somebody that doesn’t have the expertise over the programs they oversee, you know those things can be overcome and learned, but this administration has outright disdain for the people our housing programs serve. It’s had tremendous harmful consequences. The first thing the President should do, if I were President, is to make sure we have someone in charge of housing systems that cares about the people who need affordable housing and that are homeless and understands the changes that are needed for people to have access to that housing.

The next most consequential thing a President can do is make the case to the country of why affordable housing is so essential, and why housing justice is achievable, and to really educate the country about supporting individuals and families having decent, safe and affordable housing. Then putting out a budget that actually meets those needs by requesting from Congress the level of funding we actually need to end homelessness and the housing crisis in our country.

Can you talk to readers about the intersections of housing and racial justice?

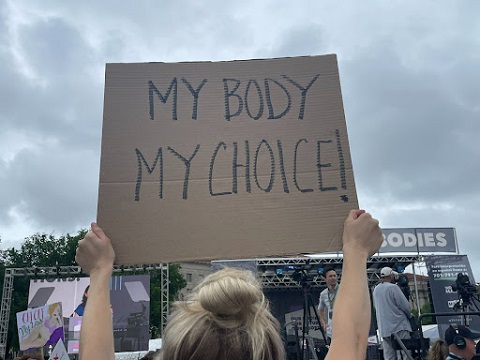

Housing justice and racial justice are deeply intertwined. They are two sides of the same coin. We can’t achieve one without the other. We have in our country a history of racist housing policies from redlining and restrictive zoning that have purposively put home ownership out of reach for Black Americans. These policies have helped create a massive wealth gap where the average white household has 12 times the wealth than the average black household. It’s created enormous housing disparities in our housing systems where black and brown people are disproportionately likely to be renters, to be rent burdened, to be low-income, and to be homeless. Black people make up 13 per cent of the American population yet make up 40 per cent of the homeless population and 50 per cent of families experiencing homelessness. That doesn’t happen by accident. That’s decades of purposeful and racist policies that had led to these outcomes. In order to reverse the harm that’s been done we have to center racial equity in our solutions to homelessness and poverty. For example, with COVID-19 where tens of billions of dollars are going to local communities. How do we ensure we are centering racial equity in response? We do it by directing those resources to people experiencing homelessness and to extremely low-income renters and people experiencing homelessness.

Climate change continues to have a disproportionate impact on poor people around the globe. We continue to see an enormous uptick in natural disasters in America. Can you talk about the connection to housing and climate change?

The connection to housing and climate change is very clear. Disaster after disaster, low-income communities and the most marginalized people are those most harmed. They are least able to evacuate prior to a disaster and they are least able to recover afterwards. Many people sometimes don’t have the social network to be able to get back on their feet. The list goes on.

The federal government consistently leaves low-income Americans behind in recovery. This has tremendous long-term impacts on individuals and families. As disasters become more and more frequent due to climate change, we must have recovery systems that center racial equity and low-income renters, or the country will just continue to lose ground as we leave more and more people behind. Our recovery system has been designed to meet the needs of white middle class people who have money in the bank. It never even contemplated low-income and marginalized people and the many needs people have for recovery, not to mention the potential loss of already existing housing stock from the disasters themselves. Our disaster recovery system in America is broken. We need change.

Are there ways people can be talking to their family and friends who may not always agree that housing is an important public infrastructure to maintain a healthy society?

It really depends on who you talk to and knowing your audience. There are a lot of different ways to approach these conversations.

I think especially right now during COVID-19 many people understand the connection between our own lives, healthcare and housing in a new way. It’s a good entry point. Some people who may have understood the connection intellectually in the past can now see and feel it in a much more intentional way. We know our collective health depends on our ability to stay home. Many people recognize the stake that we all have to ensure that tens of millions of people don’t lose their homes in this pandemic. I think starting there can open a new conversation about how all people should have the ability to be affordably and safely housed, regardless of their circumstance.

“For many renters, the coronavirus is a financial emergency. They’ve lost jobs, they’ve lost hours at work and they’ve lost wages. It’s harder than ever for people to cobble together enough money to pay the rent.”

Some people are moved by the moral argument and it’s a really strong one to make. Housing is human right, and we should continue to say so. Still, that’s not going to bring everyone in.

With others, there’s a very strong economic case to be made. Again, in this moment we understand just how important the idea of home is. We know not having a home not only harms the individual, but it also harms the community. We all pay for things like evictions and homelessness in the long-term. Inaction is expensive. We pay to allow homelessness to persist. We pay for it through increased healthcare costs, we pay for it through lower educational attainment, we pay for it through less lifetime earnings and less taxes paid. We pay for it in all sorts of ways. What if we paid for it by keeping people stably housed?

What can everyday people be doing right now to engage and support a housing justice movement nationally in America?

They can call their member of Congress. It’s the first and last thing I would ask everyone to do, and to not be afraid to do it. You don’t have to know everything. You are an expert and have your own experience and that’s the most powerful thing to share with your member of Congress. That may mean you’re calling to talk about your own housing insecurity, or the housing insecurity of a friend or family member or someone you know. That’s a powerful story in itself that your members of Congress need to hear, and they need to hear it frequently. Ask them to do something about the housing crisis, in this case, ask them to pass $100 billion in emergency rent assistance. Call them again the following week and ask them what they’ve done to follow up, and then call them again. Now is the time to hold Congress accountable!

Israel Bayer is the director of the International Network of Street Papers North America, a regional bureau of the International Network of Street Papers representing street papers in Canada, Mexico and the United States. Twitter @IsraelBayer @INSP_NAmerica

Street papers can download this interview for republication from the INSP News Service here.