By Suzanne Hanney

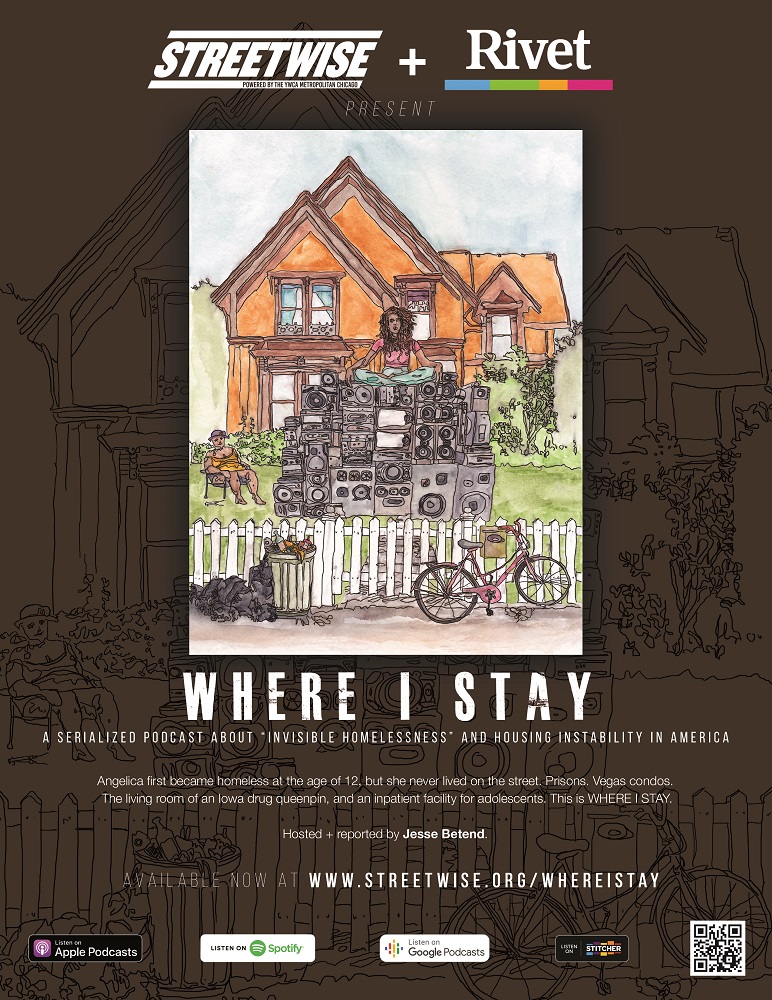

StreetWise, the weekly magazine sold throughout the Chicagoland area by those experiencing homelessness or joblessness, has co-produced a new podcast, Where I Stay, with digital storytelling organisation Rivet, about the invisible homeless in Chicago.

The podcast, two years in the making, follows the plight of the invisible homeless through the eyes of one woman, Angelica, who first experienced homelessness at age 12. The eight-part podcast hosted by Jesse Betend takes us on a journey through the child welfare and criminal justice systems, as well as the alternative economies that often feel like the only option to survive, and the lasting impact on a life.

“StreetWise saw this as a great opportunity to branch into a new medium to leverage its magazine coverage of homelessness, poverty, inequity, and inequality, and life in Chicago. The podcast featuring local, original art, and set to the sounds of those in the independent local music scene, bridges advocacy and culture in a way that lifts the story off the page,” said StreetWise executive director Julie Youngquist.

“This story is more than Angelica’s journey. She is a broader representation of what homelessness looks like in Chicago and across the nation,” said editor Suzanne Hanney. “Her experience is representative of almost all who experience invisible homelessness.”

Below, StreetWise spoke to Angelica, who gets candid about her life experience and the importance of telling her story

Meet Angelica

As Angelica was working with Rivet radio’s Jesse Betend on recording her 20-year odyssey of “invisible homelessness”, she realized the reason she wanted to tell her story was because she didn’t look like the typical street homeless image that popped up in a Google search: “The person with torn shirt and blanket living under a viaduct in a blizzard, begging for money.

“There are individuals who don’t fit those characteristics,” said Angelica, 40, whose last name is being withheld for privacy. “You do have people in a shelter who are clothed well and have a roof over their heads who are homeless. There are people who work, not necessarily begging for money or anything else but still struggling on a day-to-day basis. I wanted to give people a perspective of what homelessness is. It’s easier to put out [pictures] of individuals that’s cracked out or on drugs or eating out of dumpsters than to say it’s an individual who may have an apartment but is literally living paycheck to paycheck or sleeping on someone else’s sofa because they cannot afford $900 rent and food for their child.”

Angelica’s mother kicked her out at age 12 after she read Angelica’s diary entry about wanting to crumble up her pills and put them in her food — which would have been fatal. Angelica spent four years in her state’s child welfare system and then a variety of other situations: from couch surfing with a drug queen to serving time for a forged check she did not intentionally pass.

Angelica was invisibly homeless, that is, she was “doubled up” with other people and not on the street. But because she was not in a home of her own, she was at the mercy of her hosts, unable to determine her own destiny.

What kept her from breaking down as she hurtled through each situation?

“My son was a motivation for me. Thinking one day I would see him again. What keeps me above water now is knowing I have a little girl that looks up to me. I am a role model. Everything I am doing she’s watching me. I don’t want her to see me fail, experience the stuff I experienced. I want her to have that mother-daughter bond that I lacked.”

In Angelica’s earliest experiences on her own, what kept her going was the desire to prove people wrong, especially her mother, who was estranged from her father, but with whom she was close. “Good or bad, I was his baby.”

She also says now, however, that she attempted suicide several times, always with pills, “but something was saying it’s not my time and I had to keep pushing forward.”

The first attempt was at age 12, just before she was kicked out, when she also started cutting herself. “I would tell myself if I inflicted the pain on myself couldn’t nobody inflict more pain than what I was inflicting on myself.”

Angelica had weekly family counseling before she went into state custody, where she first began hallucinating: she saw a bandaged man standing slightly behind her when she looked in the mirror. He would be gone when she glanced away and then looked back. On her 16th birthday, Angelica’s mother bought her a ring, which she pawned. She remained in state centers until she was nearly 17.

Initially she was diagnosed with behavioral disorder and then borderline personality disorder and depression. She also got some advice from a therapist to “fake it until you make it,” which she only fully appreciated later to mean that she should model a good behavior until it became natural. Eight years ago, she was diagnosed with bipolar depression and ADHD.

There were two more suicide attempts before her father’s death a decade ago. She last thought about ending her life two years ago, when she was feeling overwhelmed.

Having lived with depression for nearly 30 years, Angelica says that changing her environment doesn’t end the sadness. She’s become good at smiling so that people don’t know. And she goes into the shower rather than cry in front of her daughter, because that triggers the 8-year-old’s tears.

What has helped her come back?

She talks to her psychiatrist, takes medication and has caseworkers: “Two really good friends I talk to and don’t hold nothing back because they don’t pass judgment. They know when to shut up and listen because that’s when I need to verbally say things out loud. Sometimes they say, ‘have you thought about doing this?’ or ‘Maybe you should do this,’ but they don’t hold nothing I say against me.”

She has also created her own family, “a group of people that love me for me,” particularly other motorcycle enthusiasts, who have become like sisters and brothers. Her bike is her freedom, she says, because you can’t worry about your issues when you are watching your speed and looking out for cars.

The turning point in her life came when she was living with somebody she calls her sister and the sister’s significant other. Angelica had gotten some weed fronted to them, her welfare check didn’t arrive and the boyfriend said, “ ‘you better figure out something.’”

Thinking he wanted her to turn tricks for the money, she went into overdrive, packed things up for storage and went to stay two weeks with someone else, where she wound up as in-home babysitter. “This is not what I need to be doing,” she realized, so she tried something different.

She went to the Trina Davila community service center run by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services, where she was referred to a shelter. After a few months there, her counselor got her into a permanent supportive housing program for which she pays 30 percent of her income.

Unlike many others in line for the program, Angelica had all her vital information – Social Security, medical records — in an accordion file. A legacy of having been wrongly imprisoned for forgery and theft, the accordion file stays close at hand. “I’m not going to let someone know more about me than I know about them.” She and her then-11-month-old daughter moved in on 17 June 2013, and they’ve been there ever since.

For the last seven years, Angelica has been employed, putting her experience to good use. She worked first in the housing facility’s child development center and more recently in outreach, providing a parents-as-teachers curriculum to frequent shelter users. She talks about development and shows activities to build attachment between parent and child.

Angelica feels her journey helps her to connect with people and build trust. She’s become the person she needed to be. “If I had met someone like me, I wouldn’t have had as hard of a life.” And at 40, she figures she’s only halfway done.

She finished her GED at age 20 when she was pregnant with her son and living with someone who encouraged her to do so, even though they later went to prison. She needs three more years to get her bachelor’s degree in youth and family services administration. Because her daughter wants a trampoline and a dog, she aspires to buy a house with a yard. She would also like to travel the United States again with someone who loves her unconditionally.

Early in the podcast series, Angelica says her 10-year goal is the shelter director’s job, but now she’s looking more broadly at homeless services. “I don’t know if I want to take over the shelter, create another shelter. I know I am supposed to help other people. I feel that is my purpose. Whatever that may look like once I graduate and touch other aspects. Maybe it’s to have permanent supportive buildings or buildings that are for low-income individuals.”

Where I Stay is available at www.streetwise.org/whereistay and wherever you find podcasts