By Emily A. Benfer

The cost of rent is taking futures

When the pandemic struck, Marlenis Zambrano was a fulltime caregiver for the children of Department of Defense (DOD) employees. For 27 years, her housing was secure, she provided for her family, and was able to save for her children’s college tuition. Her daughter attends Virginia Commonwealth University and her son is a senior at Dartmouth College—first generation college students. Shortly after DOD families pulled their own children from the daycare due to the pandemic, Ms. Zambrano’s wages were cut, and she received a five-day notice of eviction from her Alexandria home. Ms. Zambrano, who is Hispanic, is one of the many renters of color who are particularly vulnerable to eviction due to the pandemic and pushed to make impossible choices. To protect her family’s health and safety, Ms. Zambrano was forced to put her daughter’s college tuition fund toward the rent.

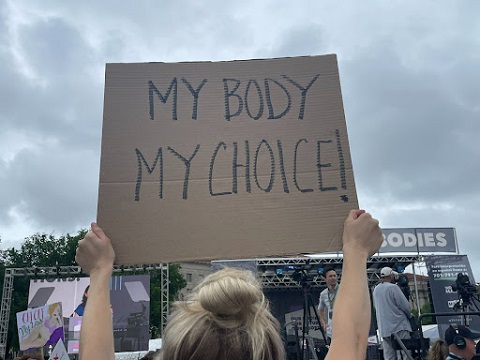

Families across the country are paying rent with their futures. “As a parent, as a hard-working mom,” Ms. Zambrano, who is advocating to keep families housed, told me, “I feel like the system is failing all the families that really need it.” The need is almost unfathomable: an estimated 50 million adults and children across the country live in renter households that suffered COVID-19-related job or income loss, with people of color hit the hardest.

The federal eviction moratorium, issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, offers temporary and crucial relief for the 30 to 40 million adults and children who are at risk of eviction nationwide. But, with the moratorium set to expire on New Year’s Eve and without emergency rental assistance to pay the mounting rental debt, renters are being pushed off the edge of the eviction cliff.

https://twitter.com/emilyabenfer/status/1336705614672769026

The struggle of Black and Hispanic renters

The human costs and housing loss will be especially heightened among people of color. Black and Hispanic landlords are in greater financial peril as they struggle to pay their mortgage and offer payment plans to renters at higher rates than white landlords. Among renters, nationally, nearly half of Black and Hispanic renters have little to no confidence in their ability to pay next month’s rent, compared to less than a quarter of white renters. These racial disparities are in great part due to decades of racially discriminatory housing laws and policies that excluded people of color from mortgages and deepened segregation lines while promoting the investment of billions of federal dollars in white communities. The sordid legacy of these laws is embedded in the cavernous racial wealth gap that propelled entire generations into poverty, poor health, and housing precarity.

As a result of the extreme socioeconomic divide, over 70 per cent of Black and Latinx adults entered the pandemic lacking the emergency funds to cover three months of expenses, compared to under half of white adults. Without a safety net when crisis strikes, the downward fall is immediate and precipitous, and recovery may be impossible. The administration’s unveiled efforts to terminate fair housing, dismantle civil rights protections and advance “not in my backyard” suburban policies only intensifies the opportunity gulf by carrying past offenses forward.

Further highlighting the sticking power of racially discriminatory policies, housing stability varies drastically by race. The percentage of Black people in a community is a greater predictor of eviction filings than poverty level in some communities. On average, even across similar education levels, Black renters face eviction at nearly twice the rate of white renters. Coupled with widespread housing discrimination in the rental market, people of color are at extreme risk of housing loss and the social and economic inequalities it causes. In the pandemic context, many of the communities most in need of COVID-19 emergency rental assistance are also communities of color.

Winnette Dickerson, a tenant leader with VOICE organizing to stop evictions, summed the effects of disparity when she told me, “We black and brown people will never be able to catch up. The plague of financial and housing insecurity will be looming over our heads. The goals of financial security & home ownership will remain a distant unreachable dream for us.” Ms. Dickerson, a longtime volunteer at a homeless shelter, also faced eviction during the pandemic after being furloughed from her job as a drug counselor.

Policy makers must act

Ending the COVID-19 eviction crisis presents an opportunity to break a link in the systemic racism chain. Yet, policy makers have abandoned their duty to prevent the clear and steep human toll of the COVID-19 eviction crisis, with some justifying inaction by assigning blame and moral lashings to the people hardest hit by the pandemic. Without rental assistance, parents will be forced into even lower-wage jobs that, where available, will hardly cover rental debt on top of housing costs, and could increase the risk of contracting COVID-19 and spreading it to loved ones. Researchers determined that lifting eviction moratoriums over the summer resulted in 433,700 excess cases and 10,700 excess deaths. Underscoring the health inequity, Black and Hispanic adults have higher COVID-19 hospitalization and death rates than their white counterparts. In addition to taking lives, the eviction crisis is on track to devastate and further disadvantage communities of color and strip any chance of true equality and opportunity in America.

Federal and state policy makers must both defend against this pressing threat to equality and repair past harms. In the immediate, this means extending the CDC eviction moratorium beyond January, as well as adopting robust state eviction moratoriums, and providing the emergency rental and foreclosure assistance necessary end the eviction crisis. Then, policy makers must redress longstanding inequality among people of color by guaranteeing equal access to safe, decent, and affordable homes in thriving communities during and after the pandemic.

Ms. Zambrano has hope for her children. “I know my children are going to be somebody one day, and not suffer the way I did,” she said. It’s every parent’s hope. It’s time every child has the same chance to reach for it.

Emily A. Benfer is health and housing law expert, a law professor at Wake Forest University School of Law, the co-creator of the COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard with the Eviction Lab and the Chair of the American Bar Association COVID-19 task force committee on eviction.