By Samanta Siegfried, Surprise

Maria [whose name has been changed for anonymity purposes] prefers to stay invisible. Around ten years ago, the day before Christmas Eve 2008, she found a new home. It was in the middle of the forest in a suburb of Bern, in Switzerland, under the shelter of an overhanging rock face. No one can see her hiding place from the outside, and only people in the know are aware of where it is. The farmer who owns the land and gave her permission to set up camp there, for example. Maria is homeless. That means that she has no official place of residence in Switzerland. She occasionally spends the night with friends, and cooks dinner for them in return. Otherwise, she lives outside. To a certain extent, Maria has chosen this life. But it wasn’t planned.

It all started with an infection from a tick bite. This was followed by countless trips to the doctor and to hospitals, where Maria got the feeling that nobody could really help her. The cortisone treatment she was prescribed was only effective for a short period. She felt harassed by the Social Security Office and was unable to cope with the disability insurance assessment. When she was threatened with court action to do with her apartment, Maria, who’s now 57, decided she’d finally “had enough” and needed a change. “I wanted to see what it was like to live like a tramp,” she says. So she took her sleeping bag and went in search of a good place to bed down.

Maria dresses neatly, her clothes chosen with care. Today she’s wearing a mid-length black dress with ruffles on the sleeves, with blue harem pants underneath. She’s wearing silver sandals on her feet, and around her neck is a turquoise chain. She’s carrying a small rucksack. She has left the few things she owns – a fleece blanket, two sleeping bags, some clothes and her food supplies – in the forest.

Very little provision

People don’t think of women being homeless, so they don’t stand out as much as men when they sleep rough. Barbara Kläsi, who runs the Church Street Work Association in Bern, thinks the main reason for this “hidden homelessness” is the stigma attached to it. “A lot of women try to play down the seriousness of their situation for as long as possible,” says Kläsi. In addition to the outreach work on the street, the Church Street Work Association on Bern’s Speicherergasse [a main street in central Bern] opens its premises every Tuesday and Thursday afternoon for people in need. Tuesday afternoons are for women only. Food is provided by Swiss Table, the charity that distributes surplus donated food, and there’s also coffee, a cupboard containing clothes, help with administrative or legal issues, or just a sofa to help people recover from the stresses of life on the streets. On average, around 18 visitors drop by, Kläsi estimates. Every second Tuesday, they also produce the magazine Mascara, in which the women write about their experiences on the street.

Women’s Tuesday at the Church Street Work Association in Bern is one of the few examples of support aimed specifically at homeless women in German-speaking Switzerland – and that’s not aimed purely at sex workers. Both the growing number of visitors last year and the visitors themselves confirm the need for it. “The mood is nicer than on the mixed days. Less chaotic, less noisy,” says Maria, who attends every week. Maria has a lot of experience of life on the street – she knows the places in and around Bern where you can get clothes and food, have a wash or earn some money doing housework, and where you can get some peace and quiet and meet other people. When it comes to finding somewhere to sleep though, she prefers to go back to her place in the forest.

“A lot of women try to play down the seriousness of their situation for as long as possible.”

Bern is not exactly a model of overnight accommodation provision for people in need. The only emergency shelters are the Salvation Army and Sleeper hostels. The latter is funded by income from the DeadEnd bar downstairs. The city itself does not run open access provision. “A disaster,” says Kläsi. There are twelve beds in the Salvation Army hostel and only six beds for women in the Sleeper hostel. In the Sleeper hostel, washing facilities are not separated by gender. Instead, if requested, the staff will check that “not a single man takes even a single step over the threshold of the women’s room.”

The lack of provision for women is usually justified by a lack of demand. Because women are not only less visible, but also less likely to be homeless than men. There are no precise figures, and the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO) does not provide data on homelessness. According to estimates by employees of social sector organisations in the cities of Basel, Bern and Zurich, women account for around one-third of those who visit their drop-in centres. On the street it is usually a little less than that. Why is that the case? Everyone comes up with the same reasons: women get help earlier than men, are more open to professional support and are usually more in control of their situation. They also usually have a better support network, whereas men often find themselves on their own after a breakup.

“Women often fight tooth and nail to avoid a life on the street,” says Manuela Jeker, joint business manager of the Black Peter homelessness organisation in Basel. She only knows a few women who have spent a long time alone on the street. “Most find shelter somewhere,” says Jeker. Sometimes with friends, often with a man. That may be with a partner, a friend or, in the case of women who are involved in prostitution, a client. Women who live on the margins of society have a particular need for security. A lot of them think they’ll find it with a man. “Unfortunately, that often turns out to be an illusion. We deal with violence in relationships a lot,” says Jeker. Separate rooms for homeless women might help. However, in Jeker’s experience, it’s not that straightforward. The Black Peter organisation used to run a women’s afternoon, but closed it down after two years. “The atmosphere among the women was tense and the potential for conflict was too great,” says Jeker. Sonja Tena, an outreach worker at the Father Sieber social welfare organisation in Zurich, has also experienced a lot of distrust among the women on the street. “Of the women we visit on the streets, 80 percent have an addiction issue,” says Tena. “Having a good time, switching off and relaxing is usually not top of their list of priorities.”

Drugs are everywhere on the street today, just as they always have been. A recent phenomenon that is worrying the outreach worker is the growing number of mentally ill people among the homeless. Although this affects men as well, it’s becoming more pronounced for women: the experts all agree that almost all of the women who live on the streets have a mental illness.

Lack of trained staff

One reason for this development is the new Adult Protection Act introduced in 2013, which focuses on outpatient treatment in psychiatric hospitals. The mostly positive thing to come out of it, says outreach worker Manuela Jeker from Black Peter, is that people have finally realised that “sectioning people is not really the answer.” However, the result has been that people then end up straight back on the street – and their first stop is the drop-in centres, which lack appropriately trained staff. One thing Manuela Jeker is sure of: “We urgently need easy-to-access psychiatric outreach specialists.”

That’s a view shared by Elfie Walter, head of Oasis for Women in Basel. Set up in 1994 as a contact point for sex workers, today it’s a shelter for all those women who have fallen through the net for one reason or another. “Most people come to us the first time with their laundry,” says Walter. As well as washing machines, there are clothes, clean syringes, condoms, a TV or simply space for visitors to have a coffee in peace.

There is currently no comparable provision for homeless women in German-speaking Switzerland, just new initiatives for sex workers. At the moment, around 19 visitors come to Oasis for Women every day, and the numbers are increasing. Including a lot of people with mental illnesses. “We now need new provision to help these women,” says Elfie Walter. Although Oasis for Women has been able to cope up to now, she believes it mustn’t turn into therapeutic provision. “The women also come to us because they are left in peace here,” says Walter.

“Women often fight tooth and nail to avoid a life on the street.”

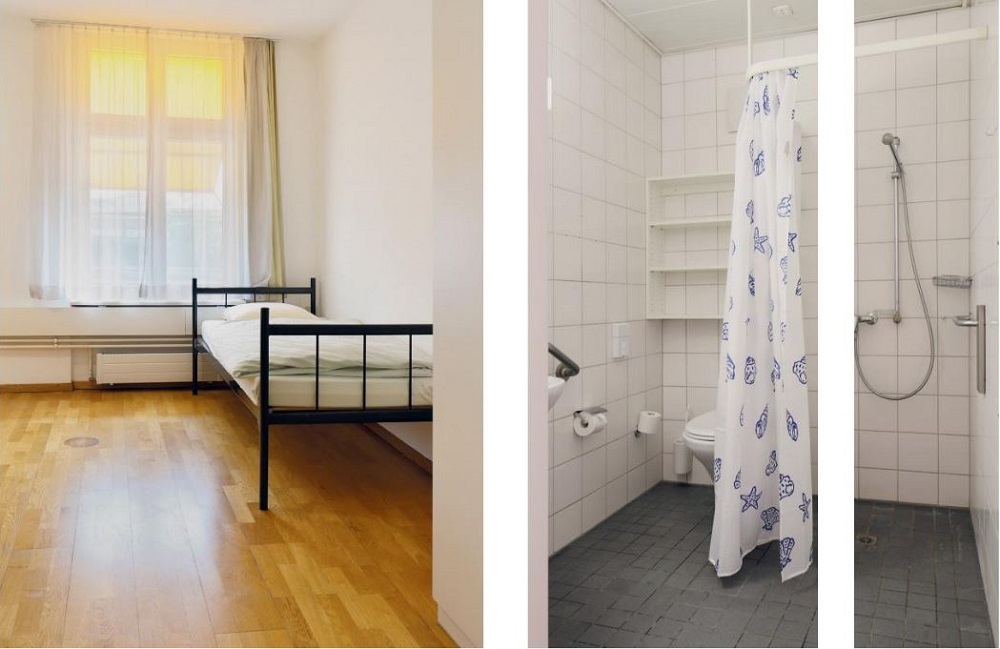

The new emergency shelter for women in Basel, which opened its doors at the beginning of September 2018, could provide some relief. The local parliament approved 850,000 Swiss francs (about £650,000) for the two-year pilot project. The local state council wrote in its application for funding that separating men and women should make it possible to create a safe haven that helps get break down the psychological barrier that is preventing women taking advantage of the provision. For one thing, there is more space and privacy in the new facility at 70 Rosentalstrasse: there are 28 beds in total available to women, all in twin rooms with private showers and toilets. Not only that, but the care provision has been expanded: in addition to the night guard, social workers are now present at Oasis for Women at least five evenings a week. In addition to the emergency shelter, there are four “rehearsal rooms” where individual women can work out whether they are ready to move back into a flat on their own. Manuela Jeker from the Black Peter Association welcomes the provision. “More space might help prevent arguments from starting.” Elfie Walter from Oasis for Women says: “You just have to try things out.” She also assumes that not all women will respond to the provision. “I also know some women who have become so used to homelessness that they wouldn’t be able to stand living in a flat anymore.”

Like Maria from Bern. She has become well established in her forest. She gets water from a nearby well and washes herself in a drop-in centre or by the river. When she gets vegetables from her tour of the food banks and containers around the city, she cooks a stew over the fire. It’s only now, as the nights get longer and colder, that Maria starts to get more worried. Will she get through the winter okay? “I’ve got a feeling that there’s going to be a lot of snow.” Apart from that, she doesn’t worry about the future much, but she says: “I can’t imagine living in a flat or house any more.”

Translated from German by Sean Morris