In 1995, 17-year-old Sara Kruzan was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole for the murder of George Howard, a man, the jury were told by prosecutors, with a family, a business, and a reputable stake in civil society. The accused – a child – was vilified as a murderer, a threat to that same society.

Little notice was taken of Sara’s circumstances, state of mind, or her induced trauma, in the lead up to her conviction. It was not until a public appeal for clemency in 2009 – a video from prison, recorded with support from Human Rights Watch, which was swept up in the fledgling days of internet virality – that Sara was allowed the space to tell her side of the story.

At the age of 11, living in Riverside County, California, Sara was trafficked into sex slavery by Howard, or ‘GG’ as she knew him, and subjected to years of forced prostitution, violence and abuse. With no one to relieve the stranglehold of power this man had over this young girl, she was driven to take matters into her own hands, shooting and killing Howard at 16. None of this information was deemed admissible as evidence at Sara’s trial. She was not considered to be a victim.

After nearly 20 incarcerated years, seven years of litigation, countless hours of volunteer and legal assistance, and several sharp turns and false hopes, Sara gained parole and freedom in 2013, but only after then California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger commuted and reduced her sentence. Since her release, Sara has dedicated her life to advocating for children who find themselves in a similar position to the one she was in – young, vulnerable, powerless, at the constant mercy of abusers both known and unknown, victims of systemic violence, and subject to a lack of care, empathy and consideration, amounting to negligence, at the hands of the US criminal justice system.

As well as working with survivors directly, Sara is part of an ongoing push, alongside non-profit Human Rights for Kids, to substantively alter laws to ensure that child victims of sex crime do not receive disproportionate sentencing – verdicts that essentially impose a “living death penalty”, as she describes it – when they commit crimes against their abusers, a fight that looks to be bearing fruit. Backed by cross-party representatives in the US Congress from Arkansas, Nevada, Hawaii and others, ‘Sara’s Law’, if passed, would give judges discretion to hand down reduced sentences for such survivors and keep them out of adult prison and in the child welfare system. The federal bill, which is making its way through Congress, will, it is hoped, inspire other states to take on the legislation, and has begun gaining steam after other high profile cases, similar to Sara’s, caught public attention, as well as due to an increase in understanding, backed by medical science, of the mental and physical trauma caused by trafficking and sex slavery.

Child sex trafficking is a chillingly misunderstood issue. In the US, while many believe the crime involves individuals, both the victims and perpetrators, from foreign countries, in reality over 80 per cent of its sex trafficking victims are US citizens. Part of Sara’s advocacy work is educating communities about this. Ahead of addressing an audience in Edinburgh at Invisible People, a conference organised by social city tours organisation Invisible Cities to spotlight unheard voices, Sara sat down with INSP to talk about her experiences and work.

INSP: Sharing what must be a painful story many times over, and even committing to doing so as part of your life and work, must be extremely difficult. How do you summon the strength to do that?

Sara Kruzan: It’s rewarding. It’s rewarding to build connection amongst others. I value humanity and I believe that we’re in this place to connect and that’s part of our purpose. I think that it creates so much healing, and this well-received feeling, when someone can say: “This has happened to me and I’m strong enough to speak about it”. It’s just very rewarding and so I wouldn’t have it any other way. It’s amazing to be able to do it actually, because I was supposed to be confined to a little cell for the rest of my life, but I’m here.

What can you tell us of your childhood and the circumstances that meant you were vulnerable to being trafficked?

When I was a child, my mother was a single parent, which I know is really common. I think her issue was impacted, unaddressed trauma that had been imposed on her in her life. And so, I think because there weren’t helpful sources for her to be heard or to have that space honoured, her behaviour projected in a way that caused more trauma, not only to herself, but whoever she came in contact with, including me. Looking back in hindsight, you’re not able to really define what that is. It’s always this assumption that she was negligent, and labels like that which impose more negative consequences.

Through my work, I’ve seen that cultures that are more socially impacted by the disease of trauma, continue to create spaces which cause more harm. Traffickers cast a look for very weak home situations. It’s as if they know exactly who their victim is going to be. Unfortunately, a lot of them are people of colour. As an adult, looking back, I can see what wasn’t being met, needs that weren’t being met at home, and this structure which allowed a predator like him to come in and to exercise his power and authority in that way. It’s an infiltration – into the home and the community – which allows traffickers to utilize their power in any way, shape or form.

What was your state of mind when you felt driven to kill your abuser? After years of abuse, why ultimately did you decide to take action at that point, at the age of 16?

There were a lot of factors that contributed to that. At that time, I personally didn’t have a strong regard for my own sense of life. I had been trying to commit suicide since the age of 10. I started self-mutilating at nine from the impacts of my mom’s abuse. Everything that I believed, my belief and values system, were based on what was given to me. I’m not saying that’s an excuse. There was this conflict. In school I felt tremendous and, as a child, I really wanted to be a doctor and, and do these amazing things. I was motivated, but the adults and the circumstances…it was like there was this constant dirt thrown on me, on this little plant that was trying to grow, and after a while, the disregard for myself and for humanity placed me in a space where I didn’t really begin to question my life.

There was also the constant impact of being sexually abused, because there was a point where I just surrendered and I was like, whatever – whatever would happen, it’ll happen. So there was hopelessness. There was desperation, there was deep grief. But I also wanted it to stop. I had this internal civil war going on, something telling me to know that this harm that was being imposed was completely not right. And then when I did take his life, I immediately apologised. It was very difficult. In our system in America, there’s no honouring of the victim who’s committed a violent act and there’s no advocacy. So for a long period of time, after being put in an institution, I basically had to figure out who I was, if I was a monster. I mean, that’s what everyone was telling me. My core being, my essence, though was innately against that, saying I wasn’t. I don’t know what it was that gave me that knowledge that I was worthy to be seen.

When the sentence was being handed down, did you understand what was happening?

There was an awareness, but the legal jargon itself? No, I didn’t understand half of the language. I was aware of my attorney’s mannerisms, his exhaustion, which I felt was my fault. I felt the power and the authority of the men in the room, which was intimidating. It was intense. There was a disassociation happening too – I was there, and then I was not. It was short – two and a half days and then it was done. I remember sitting in the cell and doing odds with tissue paper – basically if these small scrunched up pieces of toilet paper rolled off a block, I would be convicted. That was how basic my understanding was. I did not grasp the concept that they were going to sentence me to die in prison.

How can a judicial system have the authority to send a child, particularly one with the traumatic experiences you had endured, to prison for life, without the chance of parole?

The way we treat our children shows who a country is, and I’m not proud of being American because of how it treats its children. Not only because of my experience, but through the work that I do, the more I dig, the more I see – once you know, you can’t un-know. In my case, the judge had other options – he could’ve gave me 25 to life. He disregarded that. He wanted me to have a death sentence, a living death sentence. And then he imposed a $10,000 fine towards victim’s restitution that I had pay throughout my sentence.

Why do you think the judge chose to interpret your case in that way? Do you think they made this decision based on the technical aspects of your case, or do you think there are deeply engrained prejudices – who you are, the way you look – which made them fall this way?

I don’t believe it would’ve happened to a child that wasn’t of colour. When my lawyers asked for records, they found that the judge had even passed comment on this when instructing the jury, something along the lines of “don’t be persuaded by a young, attractive African American”. These are statements which should not apply when talking about a kid. There was also the fact that George’s clients were people that might not be considered your average person that purchases children. These people were police officers, dentists. In fact, the judge identified GG basically as a businessman, saying his business had been destroyed. There was a lot of verbal protection for him.

“The way we treat our children shows who a country is, and I’m not proud of being American because of how it treats its children.”

It seems that this person, a perpetrator, was handled with more empathy than you, a victim. Did you feel the injustice of it all at the time?

I didn’t even cry. I didn’t have any reaction, I think because my body had become so used to this deeply seated grief and trauma. After the sentencing, they took me back to juvenile hall. They put me on suicide watch again. If the system imposes a sentence and then turns around and says, “Oh, let’s put this child on suicide watch because they might kill themselves”, I think that’s very telling that they’re very aware of what they’re doing. After a couple hours, they transferred me to the county jail. I was 17.

Without condensing nearly 20 years of your life, what can you tell me about your time in prison and your relationships with other inmates?

Actually some of my experiences there have made me feel like one of the richest people in the world, not by monetary wealth, but through human connection. It’s a concentrated environment that is, in a way, designed to be degrading. So, when you connect with another human being, and you’re raw and real, there’s such a depth of wealth in there. Imagine the different people and the intimacy, the conversations. You see people at their ugliest, their most caring, their most desperate, most loving, most gentle. It’s very powerful. I think that’s partly why I do the work I do now – I’m infused with the journeys of all those other people.

That work means you have learned more about the systemic issue of trafficking. Do you think the misunderstanding around who is involved in trafficking and its causes contribute to the injustices of cases like your own?

Absolutely. I think if you admit the ugly, then you have to be accountable for it. So it’s easier to say, “actually this is only happening in developing countries, there’s nothing going on here”. But the reality is, it’s your neighbour. I’m shocked that people are shocked when they find out about this information, because it’s their husband or their partner, or it’s the preacher at the church. No one wants to admit this dirty little secret, they just want to hide it, and that’s a social disease, and the more you do it, the more intelligent it becomes. And I think at this point now it’s smarter than the people.

While in prison, at what point did you begin to hope that there was a chance you could get out?

It wasn’t really like that. It was more my curiosity, my Joan of Arc spirit and energy. I was like “if I’m going to die in here then I’m going to die trying to get out”. I was really motivated by that. And also, I was there with these other women, it was a community, so I thought why not make the best out of it. There was so much liveliness, hope, inspiration, smiles, camaraderie, sharing. I was freed on the inside. I didn’t need to be physically free to know that I was free. So when I spoke to my lawyers, over this seven-year period of litigation, I had this optimism. I was like: “Look guys, it’s going to happen. It may not be time yet, but it’s going to be okay”.

And it was really interesting how it unfolded. I had no clue what YouTube was, you know, because, when I went in, I didn’t know anything about computers and the ability of the Internet. When we did the video to change the law, the intention was to help legislators understand, but somehow that video went viral. I had no idea what was behind it. And the next thing I know people are reaching out and students are moved to lead this campaign to let everyone know on an international level that this had happened.

So, now the US has this bill in Congress, and it has been introduced by a Republican [Rep. Bruce Westerman of Arkansas]. To me, outside the US, that says not only is there a need for the law on this subject to change, but there is also an appetite for it. And a non-partisan appetite, because it looks like even those you’d expect to not necessarily be behind the bill are supporting it. So why has it taken such a long time to get to this point? And, linked to that, if there is a big systemic change required, do splashy cases like yours and Cyntoia Brown’s [Brown, who was convicted at 16 after killing a man who had hired her for sex, received calls from celebrities such as Kim Kardashian and Rihanna, to receive clemency], actually do more harm than good, when so much attention is placed on individuals, and not the wider deeper problem?

The reason it has taken so long is that the accountability factor is going to require people to change the way their morality is defined when it comes to children. We’re valuing our children more, so we’re more open to just giving them the right to be children. Also, the science is showing the impacts of trauma on the brain and how that leads to certain actions. Now that we have that evidence, and we live in a world where knowledge can be instantly shared, it can validate the argument that things need to change.

In terms of the sensationalism around individual cases, I appreciate the fact that people are aware there’s a problem, but yes isolating it to that shows we can still do better, because there are so many other cases, and it’s far too common. Hopefully the fact we have been highlighted, we’re able to now say “let’s go get everybody else”.

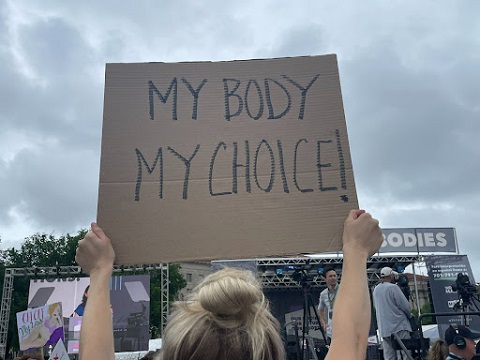

I see parallels with your case, and cases like yours, that also suggest that actors of power in the US, and probably across western society, find themselves unable to apply empathy to the people who need it most. Whether it’s a child who has been sex trafficked and then forced to murder their abuser, or a homeless person without access to social benefits being criminalised simply for sleeping on the street, or a young black man who has been shot by a police officer, only for that police officer to face no accountability. There seems to be confusion between powerful, usually white, usually male, people of privilege, and marginalised vulnerable people, and who receives the label of victim, and who receives punishment.

Racism and prejudice, in American culture, is very strong. I think it is actually the root and basis of our country. My mother is white; my father is African American. I have experienced a sense being difficult to accept in both communities. Social assaults are taking place on subcultures throughout the country. There’s a huge race and prejudice issue – it’s dominated by white male power and privilege. We can’t seem to all just come together and see each other as human beings. If we don’t change our behaviour, that won’t change either. In the world of child sex trafficking, mots men who purchase children are privileged and powerful. It’s the sense of entitlement being their power and privilege that makes them think anything, no matter what it is, is at their disposal.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This story is available for republication to INSP members via the News Service.