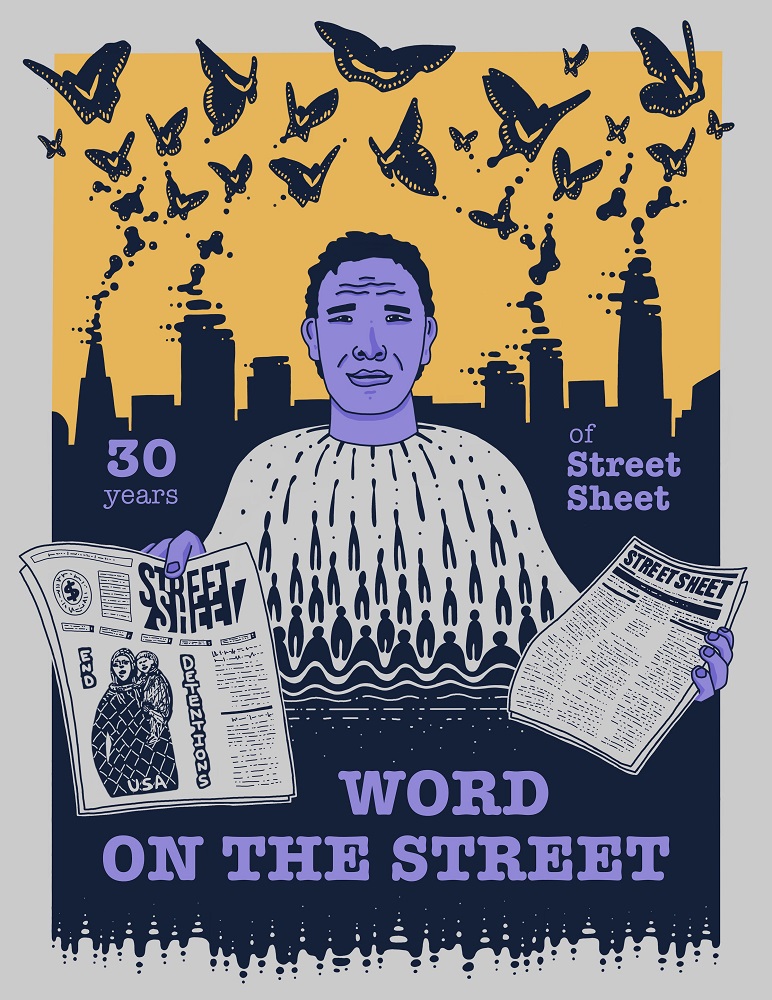

San Francisco street paper Street Sheet is celebrating its 30th anniversary this month, making it the oldest current member of the street paper network.

When the publication was established three decades ago – under the stewardship of its activism-focused umbrella organisation the Coalition on Homelessness – its founders intended for its existence to last merely a few years, expecting that it would contribute to successfully addressing homelessness in the city, explains the street paper’s current editor Quiver Watts.

Perhaps few at the time could predict that rising property prices, inflated by the arrival and continued presence in and around San Francisco of multi-billion-dollar tech companies and their wealthy employees, amongst other factors, would plunge the city into an ever worsening housing crisis. Coupled with a lack of appropriate shelter for those who do find themselves on the streets, and harmful, negative criminalisation policies by local government, Street Sheet’s existence is even more necessary today.

“It still seems like a possibility that homelessness could come to an end in San Francisco,” says Watts. “But the city refuses to offer appropriate solutions to systemic issues, favouring criminalisation of homeless people over creating affordable housing.”

As with street papers across the world, Street Sheet offers a credible and respectable solution to those unable to find a source of income, although Street Sheet’s model differs slightly from sister papers in other parts of the US and the rest of the world – vendors receive copies of the street paper without having to pay, and so keep all of the profits from the subsequent sale. That has gone from bring $1 to $2 today.

But just as important, says Watts, is being able to give those sleeping rough and without a home of their own, a voice which catches the attention of readers. “The reason Street Sheet has survived as a publication is because we are really telling stories that mainstream media outlets don’t cover here. And these aren’t just feel good stories; these are stories about how people are surviving despite all the obstacles they are up against. These are the things that are happening that regular people don’t get a chance to read.”

Other than the price increase, over the years, the final product of Street Sheet has gone from being blocky and text-based, to something a little more colourful and creative without losing any of its grassroots, radical, anarchic, advocacy-led character. This year, vendors also began offering cashless payments as a way to buy the paper. And Watts hopes that, going forward, Street Sheet will be able to pay contributors a fairer wage and launch a podcast.

“We’ve also gotten a little less snarky actually – sometimes I think we can up that again,” says Watts, laughing. “But unfortunately, something that hasn’t changed is that I can pick up an issue from any point over the years, and the stories and headlines are always focused on the same things: criminalisation, lack of shelters. There’s only been very minor change. Nothing structural. And there are more people homeless now.”

“Ending homelessness is possible, but will take a radical redistribution of wealth. It probably won’t be achieved until the end of capitalism, and I hope I see that in my lifetime.”

The picture of poverty and homelessness in San Francisco, and much of California, remains bleak, even as some of those most responsible attempt to improve this regional issue.

“The housing crisis here is so terrible it would have been unimaginable to me ten years ago,” says Watts. “People are unable to afford a place to live. 70 per cent of the homeless population are people who have lost their homes. There’s this picture that people are flocking to this thriving, resource rich city, but that isn’t true. People are being priced out and having to leave.

“People – mainly black people – who grew up here, now can’t afford to live in the city. And now tech upstarts are replacing them. The cultural conflict is very stark. It’s impossible to be around and not palpably feel the wealth disparity.”

Watts does have hope that the situation will improve. “I do think the end of homelessness is a realistic goal. If tech companies pumped revenue into the city and the San Francisco authorities could be trusted to use that money well and turn away from insidious criminalisation towards housing, it can happen.

“It will take a radical redistribution of wealth. I believe though, that it won’t happen until the end of capitalism, and I hope I see that in my lifetime.”

Happy 30th Anniversary to @StreetSheetSF! 🎉

Our San Francisco #streetpaper is celebrating the milestone with a special anniversary edition – check out the beautiful cover art 🎨📰 https://t.co/8BkJVQ12WA

— International Network of Street Papers (@_INSP) November 4, 2019

As for being the oldest member of the street paper network, Street Sheet’s inclusion has often been buoying. “It’s been really helpful knowing you are a part of a broader movement, and seeing people’s stories getting out across the world,” says Watts. “It means people are taking notice everywhere, not just of us.

“The main thing about street papers that is viable, other than the income, is that it is a creative outlet. When our writers, many of whom have lived experience of homelessness and poverty, are republished by other street papers, it’s such a big thing. Hearing from them is the best way of having genuine solutions come to light, and homeless people need to be at the centre of a street paper for that to happen.”

In Street Sheet’s current issue, the voices of vendors and staff that have been involved with the street paper for a long time are being given the spotlight.

Vendor Waverly Walton has been selling the paper since 1996, writing in the issue: “[Street Sheet] helps individuals that need it, gives you a motivation to do your work and something to do during the day. You’re really doing your part. I go out there to give people information on how they can help, and let folks know we need their support, cause it’s not getting better.”

Paul Boden, founder of the Coalition on Homelessness, wrote: “Giving people the voice of our community and educating the public to respect all people’s human rights pretty much sums up what Street Sheet means to me. While our desire to put out the paper came largely through our incredible frustration with how we [the homeless community] and our issues are defined in the mainstream media, our goal with the paper always will be to show our creative talents, and to express our collective knowledge as the true experts on the systems that impact our lives.”

Former editors of the street paper also reflected on how Street Sheet has changed over the years.

Sam Lew, who was editor from 2016-17, and now works as a policy director for the Coalition on Homelessness, wrote about how climate change rose to be an important issue, as out of control wild fires in California disproportionately displaced poor and homeless people, with little safety net in place.

Matthew Gerring, editor from 2013-15, sang the praises of Street Sheet’s involvement in promoting Prop C, a proposal to increase funding for city services for the homeless through higher taxation for big business. He wrote: “There is significantly more public support and money for the construction of new homeless shelters, and for services for homeless people generally, since I was the editor. I don’t think anything like Prop C could have been achieved in that time period. For whatever reason, despite the situation remaining basically static, there is an enormous amount of political will to ‘solve’ homelessness that simply didn’t exist when I ran the street paper, and to the extent that Street Sheet aims to elevate the challenges faced by homeless people in the general public discourse, you could call that progress.”

Street Sheet may be an extremely powerful creative outlet and awareness-raising tool, but this is evidence that the street paper has substantively impacted the issues closest to it, something it will continue to do for as long as it is needed.

Below, watch a documentary produced by Street Sheet, made in 1992, about the daily work of the street paper