When Sorgenfri underwent a redesign at the start of 2019, investigative projects became a focal point intrinsic to the new style of the magazine. What spurred the decision to have them both connected, and why pivot to investigative stories specifically?

Our vendors are perhaps the most disadvantaged group of people in our society. They don’t normally have a voice in traditional media. As a street paper, we ought to, in terms of journalism, take them and their situations seriously. This group of people, and society, needs critical and investigative journalism around these themes. And we are the only media outlet that has this special access to this group of people, and the troubles they face. We see it as our task to produce thorough, quality journalism linked to their situations (drugs, mental health, crime, homelessness), and believe that this is a very important direction for a street paper specifically.

We also believe that it is very important to be clear about which kinds of articles we publish in our magazine, so that people know what to expect from us. Therefore, we now are crystal clear about just publishing pieces that is about drugs, mental health, crime and homelessness. Our goal is to create debate and set the agenda.

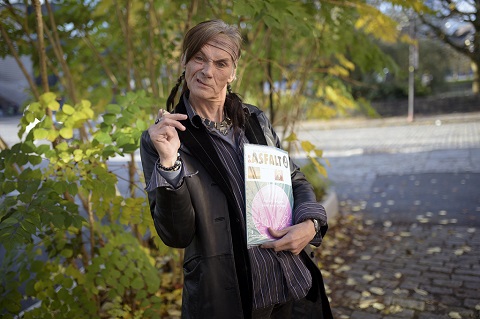

The big piece is always on the cover from month to month.

We also want people to buy Sorgenfri because of the importance of the pieces, in addition to helping the vendors. We know that quality journalism sells, and also creates the most loyal readers. The new design needed to reflect all this, and we chose a more strict layout than before. It’s more newspaper-like, more “serious” and the buyers also get references to several articles on the frontpage – which can give them more reason to start reading.

Can you briefly summarise the investigative stories you have published in the street paper so far, and the main themes they explore?

January:

Investigative piece: Treatment for drug addiction

We dived into the situation for drug addicts in Norway that want help to get clean with LAR (Drug assisted rehabilitation), and live a better life. The documentary follows Sorgenfri vendor Robert, a drug addict who is struggling with getting the help that he should get. It got so difficult for him at one point that he tried to take his own life. The piece reveals that there are major differences in terms of the help the patients in LAR are getting from region to region, even though the hospitals ought to give the same rights to treatment over the whole country. Worst off is St. Olavs hospital in Trondheim (where Sorgenfri is based).

February:

Investigative piece: Dependants of drug addicts

Many people are affected by a person’s drug addiction. This documentary follows the mother of a drug addict. Sorgenfri have followed her since 2015 – through times when her son was clean and when he fell into drugs again, living homeless on the streets. This investigative piece reveals that a whole lot of relatives of drug addicts get sick themselves – anxiety, trouble sleeping, stomach diseases, burden diseases – many are taking sick leaves from their jobs. At the same time no one knows how many are affected, and there is a dark corner in the treatment system for this forgotten group.

March:

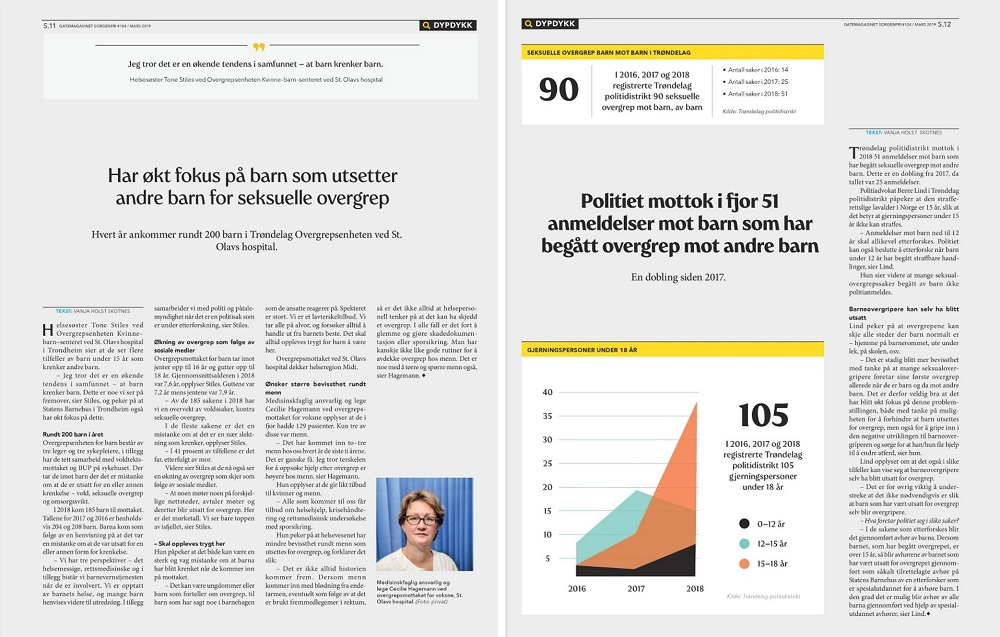

Deep dive: Sexual abuse

The piece follows “Johan”, a man who was sexually abused when he was eight years old – by another child. He tells his story in the piece – both about being abused by a child, and dealing with this later in life – as a man that has been sexually abused, with all the taboos around that theme. The piece reveals that the number of police reports on children sexually abusing other children in the region of Trøndelag have doubled in a period of one year. The region’s hospitals are now having increased focus on this theme.

April:

Investigative piece: Patients escaping from the psychiatric hospital

Since November 2018, Sorgenfri has tried to get access to public information that shows how many patients have escaped from the region’s psychiatric hospital. It turns out that the hospital doesn’t keep count. This investigative piece follows a mother that has a son with a severe psychiatric illness – he has managed to escape from the hospital four times.

May:

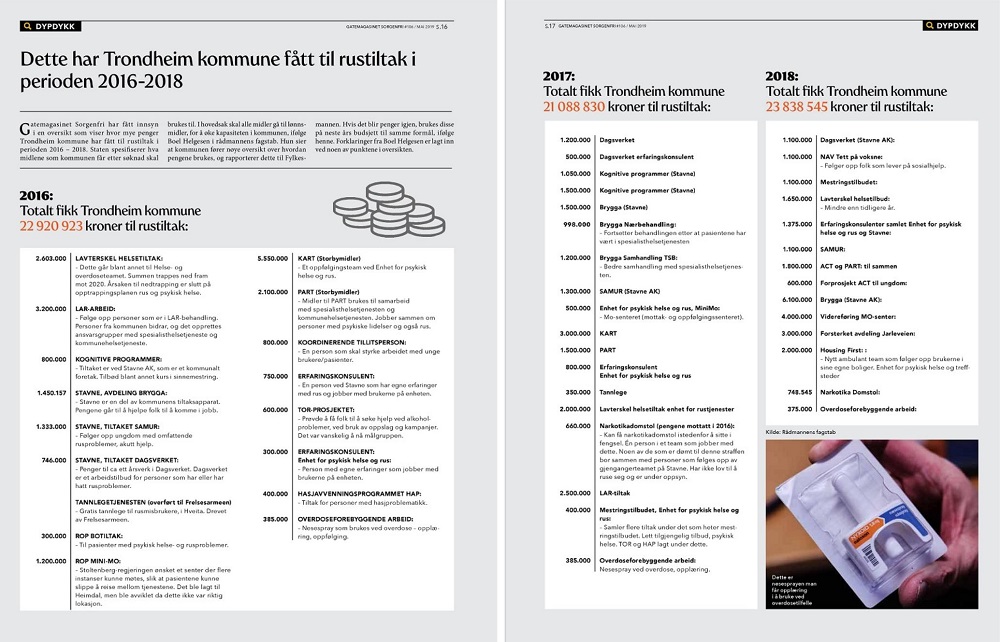

Trondheim’s Health and overdose team has been subjected to cutbacks, without this being politically treated. At the same time Furulund, an accommodation for addicts, has been closed down, without the users having received another offer. In the piece, we also surveyed an overview of how much money the municipality has been using in offering help to addicts since 2016.

Do you limit yourselves in the subject matter you choose to investigate and, if so, why are these the themes you decided on?

Yes – we only write about crime, drug issues, mental health and homelessness. The reason behind that is because these are the issues/situations our vendors – the most disadvantaged people in our society – struggle with. We need to take this seriously, and take ourselves seriously as a street magazine – and have a crystal clear editorial line in our magazine. We are a voice for this group of people, this is Sorgenfri, and in terms of journalism our mission is to do investigative journalism on these kinds of issues and create debate – which hopefully will lead to a change in the long term.

Can you roughly outline your process from inception to completion for an investigative story, and hit on the most important points of the process?

We work a lot with getting access to documents that should be public. For the most part, that is how our work with an investigative piece begins. The work can also begin with a tip we get, or just talking with people, being in political meetings or covering a trial in the justice system. The key is to look for what’s not being said, details or atypical angles. Nonetheless, in the beginning of each story, we seek to get access to documents or information someone wants to keep secret.

Normally, I do the work with getting access to the documents/information that should be public. This is because this takes time – and we don’t have a whole lot of money to spend on freelancers. Then I hire a freelance journalist and a freelance photographer to do the rest of the work, and I spend some time guiding them throughout the process.

When we have dug up enough facts to do a story, we always seek to find people that can give the story a face. We also speak to many sources to get the piece balanced, checking facts, and we are extremely thorough when it comes to following Norway’s Vær Varsom-plakat (Ethical Code of Practice for the Norwegian Press).

It’s vital to keep to all of the rules in the Ethical Code of Practice for the Norwegian Press. If a story is in conflict with this, it will not be published.

Other than that, it’s vital to seek to dig up information that is not known from before – to give the readers and the society new points and tools.

After the piece is written, we spend time fact checking and taking extra rounds on the ethics. Every piece needs to be bulletproof.

Each piece is normally finished at least about two weeks before going in to print.

What is the biggest obstacle/challenge you, as an editorial team, face when setting out to work on one of these stories?

To get our hands on all the documents we think should be public – not only parts of it. Also, sometimes getting in touch with sources – getting them to tell their difficult, and sometimes taboo, story openly.

How do you deal with sources that are antagonistic toward the aim of your story, perhaps because they are being criticised?

The story is going to run regardless whether they are happy or not. As long as they are getting reasonable time to answer all the criticism [referencing the Ethical Code of Practice] it’s all good. No editor should ever be “bullied”, pressed or threatened not to publish a story. Every editor needs to be independent and make her/his own decisions on what to publish or not. If we don’t have that, we don’t have a free press.

When it is finally ready to put on the page, what tools do you use to illustrate the story, and what proportion of the magazine does it take up in each issue?

We use photography and graphics (to illustrate numbers, statistics) and sometimes illustrations/drawings. Each piece takes up about 10-16 pages in each magazine (total: 48 pages).

What is the impact on Sorgenfri’s resources in terms of the number of staff involved in a single investigation, and the amount of time one takes from beginning to end?

Sorgenfri only has one journalist (me, 100% per cent). Planning is the key to using both time and resources well. We think long-term. Last fall, when I started this job, I started planning the big pieces for 2019, and doing some of the pre-work. I’m always working on an investigative piece, at the same time that I do other pieces and other tasks that comes with the editor job. Some pieces may take a year, others take a few months or weeks. Typically, there are two people involved in our investigative pieces – a freelancer and me. If we have a particularly difficult piece, I seek help from colleagues and mentors in other newspapers or press organisations.

Do you have any advice for street papers on an extremely limited budget and with few resources who might want to set out on an investigative project?

Plan the pieces long-term, work on several potential stories at the same time, do the pre-work yourself, be patient, work continuously and have a clear thought about what needs to be done to finish the particular piece – and then hire a skilled freelancer or engage your own journalist.

Don’t rush the pieces, but work on them for a long time – at the same time you are doing other pieces.

Has this focus on investigative projects had any noticeable impact on vendors, be that in terms of magazine sales or otherwise? Are there any measures of success?

Some of our pieces have led to a direct difference for the person (in this case, a vendor) involved.

It’s a tough question about measures of success and sales. We have increased the sales every month since January, and so far in April we have sold over a thousand magazines more than Sorgenfri sold last April. But I believe there are many factors involved, not just our focus on investigative journalism – however, I am sure that the focus is a part of it and we have gotten lots of good feedback.

Some important things cannot be measured, for example the increased awareness we give Sorgenfri’s readers of the situations of this group [whose interests we are covering]. Often pieces that other media normally don’t write so much about. And the continuous focus on things that don’t work in our society – in order to get them sorted out. Now, the magazine makes both a direct (instant money) and indirect (creating debate, more awareness about their situation in terms of thorough journalism) difference in the vendors’ lives.

The role of your street paper as a media outlet in Trondheim and Norway seems to have shifted with the pivot to investigations and deep dives – what makes a street paper’s outlook on these projects significant?

The group of people we are covering, is not likely to have a voice in other, bigger newspapers. We feel it is in its place to do high quality journalism about these issues in a street paper. If people want to read “happy news” or soft news about celebrities, they can do it elsewhere – we seek to set the agenda about difficult situations the people of the street face.

When deciding to do this, were there any media outlets (other street papers?) you looked to for advice or inspiration?

When I applied for this job, I already had a clear thought about the magazine doing more investigative journalism, and being crystal clear on which stories we are publishing. In the redesign process, we looked to Politiforum, a magazine for police staff in Norway, which also comes out once a month. They sometimes have really good investigative pieces, and only have a few hired journalists.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.