By Dominik Galliker, Surprise

Are you nervous? “A little bit.” She laughs, embarrassed. “I haven’t eaten anything today,” she says, clutching a little bag of chicken nuggets that she bought from the train station. “I didn’t want to eat until I knew that everything would go well.” The train arrives. The 14.34 to Fribourg, Lausanne, Geneva, Geneva airport.

“Shall we sit upstairs?” asks 31-year-old Laila, her lips painted a matt pink. “I didn’t tell anyone, you know.” She says, once we’ve sat down. “It’s supposed to be a surprise. A big surprise for everyone. I’ll upload a picture on Facebook as soon as he arrives.” The train pulls away from the platform. The station slides by, then the riding school, then the river, the bridges. “He misses Bern a lot,” she says.

***

Can you remember it all, Laila? It was a little more than one year ago – 8 December 2015 to be exact. Laila and Toufik had an appointment with the immigration authorities. A nice appointment, they thought. “Do we have to talk about it?” asks Laila, chewing on a chicken nugget.

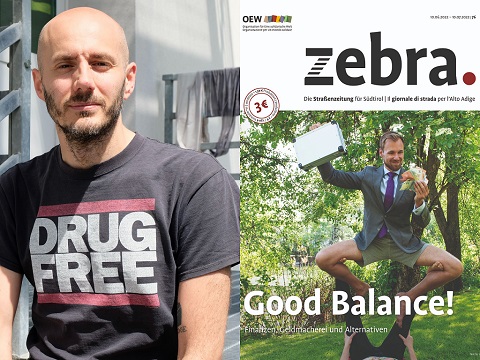

She had been making preparations for her wedding. They were at the registry office. At the desk for couples without papers. They had been together for a year and a half. Laila, a women’s rights activist from Yemen, had been given refugee status a long while ago. Toufik, a Moroccan looking for a better life, lived in an asylum centre. His application for asylum had been turned down the year before. He was an illegal immigrant, sans-papiers. However the authorities were missing a Laissez-passer – a pass to get him back to Morocco. Toufik was permitted to remain. He lived in the asylum centre, signed in every day to confirm he was there, received 8.50 in Swiss francs per day, to buy food. Like hundreds of others who were turned down.

***

Everyone is allowed to get married in Switzerland, it is a human right. You even get a residence permit after getting married, but you need to have the right papers. Toufik was missing one: a certificate of citizenship. In essence, a valid passport.

***

“Look at this!” Laila rummages around in the plastic bag she has brought with her. “I bought him a present.” She pulls out a scarf, black, with the label still on. “I’m sure he doesn’t have enough warm clothes with him. He always forgets. In Morocco it’s always so warm…” An announcement interrupts her. Next stop: Fribourg. The Moroccan embassy didn’t want to give Toufik a passport. Illegal immigrants don’t get passports. They told Toufik that he needed to apply for a Swiss residence permit. To get this, he needed to have a passport.

It is this dilemma that Laila and Toufik wanted to explain to the immigration authorities at their appointment on the 8th December of last year. The civil servant had invited them there to talk about the wedding, as far as Laila and Toufik were concerned.

“We asked you to come here today to sort out your residency status,” said Alexander Ott, head of the Bern immigration office. He split the pair up – Laila went into one room, while Toufik was led into another. Or so Laila thought.

Two immigration officers questioned Laila. They asked her strange things, like whether or not she knew that Toufik didn’t have a residence permit. That he wasn’t supposed to be here. They questioned her for two hours, Laila told us later. Then they said that Toufik wasn’t sitting next door, he had been taken into custody. Arrested. Administrative detention while they prepared everything for deportation.

***

Laila falls silent. The train has already passed Lake Geneva. It’s cloudy. The trolley rolls past us. Someone orders a cappuccino. After a while, Laila says, “Please don’t write anything negative about the immigration police. Or about Mr Ott. Mr Ott is a friend.”

Toufik was in jail for almost three months before he gave up. Voluntary repatriation to Morocco, 25th February 2016. “Let’s talk about something else,” says Laila. Next stop: Lausanne. “Oh wow, we’re almost there already. Just one more hour.” Laila takes a mirror from her bag, and make-up. She tops it up, although she’s already perfectly made up. She pulls out her phone and checks one more time. Train’s estimated arrival at Geneva airport: 16.27. Flight from Casablanca due to land at 16.20. “We’ll have to hurry,” says Laila.

***

Toufik first came to Switzerland in 2012. He never intended to stay. In his hometown of Rabat he was a carpenter, but he didn’t earn enough money to be able to start a family. His partner left him for another man, he tells us. He decided to leave. He managed to get onboard a ship, dodging the border police in Montpellier. He travelled to Italy. He lived in abandoned houses or on the street. He worked as a chef, then at a market, earning 30 euros a day. Shortly before the onset of winter, the business was checked for undocumented workers. When he couldn’t show his papers, he had to leave. “I just want a legal job with a steady income, a normal European life,” he said after coming to Switzerland. “Can’t I just stay here for a few months and then go back to Italy in the spring?” he asked. “I’ll freeze to death if I go now.”

The State Secretariat for Migration checked whether they could just send Toufik to Italy or to France. Negative. The Dublin Agreement states that because Toufik was never registered in France or Italy, he couldn’t be sent back. There were only two options: he could apply for asylum in Switzerland, or he would be sent back to Morocco. “I wouldn’t fly back to Morocco for all the money in Switzerland,” says Toufik. And then he makes a hopeless application for asylum. In a country where he had no intention of staying.

***

The train arrives at Lausanne station. Passengers are waiting by the doors for the doors to open. “Hello?” A phone call from Rabat. A quick conversation in Arabic, then the connection goes. “Toufik’s family,” Laila explains. “They took him to the airport, to Casablanca.” She tries to call them back. No connection. “It was an emotional farewell for them,” she says. “They hadn’t seen him in seven years. Before he was deported, he had been in Europe illegally for seven years. Can you imagine? Seven years!”

***

One week before, at the immigration office. Mr Ott is in his mid-fifties with a moustache and a short haircut, grey, with rimless spectacles. A man with authority, and always media-ready. Why was Tourik arrested, Mr Ott? “Mr. S. had gone into hiding after the decision was made to remove him. A legal order was made to have him deported,” said Alexander Ott. Toufik had actually gone into hiding and travelled to Germany, but this was a long time ago. He returned to Switzerland and had been in the asylum centre for more than a year. How is this supposed to work? “The immigration enforcement authority doesn’t work with case-specific information,” Ott explained. “However, we clarified it with the appropriate authorities before he was detained. They confirmed that the deportation order was still valid. If Mr. S. had obtained the necessary documents for his marriage, we would have been able to assess his case a second time, but he didn’t have anything to support him and he was in Switzerland illegally. In cases like these, the immigration authorities have a very limited margin of discretion. We were forced to act in accordance with the law.”

***

The train leans into the curve. The weather has cleared up outside and we can see the castle in Nyon across a lake. It’s just after 4 o’clock. “I thought about dying my hair red,” says Laila. “Not all over, just a little bit, underneath.” She checks her phone, no message from Rabat. “But then I remembered that Toufik doesn’t like red hair, so I didn’t do it.”

***

How did you two meet, Laila? It was in 2014. June. They were both in an asylum centre in Thun. Laila was waiting for a decision on her asylum status. She had been doing an internship with a human rights organisation in Switzerland, and during that time the situation in Yemen had intensified. This is when Laila decided to apply for asylum. She met Toufik in a nearby shopping centre. All of the asylum seekers went there, because there was free internet access. He looked like an Arab. “Are you from Yemen as well?” She asked him, “from Morocco”, he replied. And he wanted to know how long she had been in Thun. “Four days”, she replied. He went into a shop, came back out and said: “come with me, I’ll show you the town.” And that was it.

***

Laila checks her phone, sets it aside, and plays with the ring that she wears on her left hand, turning it around on her finger. A wedding ring? “Yeah”, says Laila. “We’re already married, just not on paper.” There was a traditional Islamic ceremony at the asylum centre in Thun. A big party. Someone had put on some African music and everyone was dancing, even Toufik. “It’s real gold”, says Laila. “But from Morocco, so it wasn’t so expensive. Toufik didn’t know what size to get. He just bought the biggest.” She has wrapped sticky tape around one side of the ring to make it fit.

***

Subject: press enquiry. An email to the immigration service of Bern: why was there an order to arrest a man who had been living for such a long time in one of your asylum centres? And why was he only arrested when he showed up at the registry office, wanting to get married? The answer: “We would like to thank you for your enquiry. We regret to inform you that we are unable to express ourselves to the media. Thank you for your understanding.” And that was that.

***

Geneva, central station. The train has barely pulled up to the platform when Laila stands up, grabs her coat and wraps her scarf around her neck. Just one more stop: Geneva Airport. “I need to do my hair quickly at the airport,” she says. And adds: “I hope Toufik is well dressed. I told him to wear something smart.”

***

We sent a request to the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM): application for access to files in the case of Moroccan national, Toufik S.

After some time, the SEM sends us 200 pages of documents that have been redacted in places. It is Toufik’s story from the perspective of the authorities, from the first interview until the decision to deport him. These documents show that in the summer of 2014 the SEM tried, for the first time, to get Toufik out of the country. They wrote to the Moroccan embassy asking them to identify him and demanding a Laissez-passer. No answer.

In January 2015 the SEM tried again. “The person in question does not have leave to remain in Switzerland, and for this reason will have to leave without delay.” No answer.

The SEM sent a third letter in May 2015. “Respectfully, we would like to remind you that we are still waiting for a response in this matter.” No reaction. The fourth letter wasn’t sent to the Moroccan embassy; they sent it straight to Rabat. The answer came within a few days: a promise that the Moroccan authorities would issue a Laissez-passer. This was on the 12th November 2015. Just one month before Toufik and Laila would go to the immigration office for their marriage documents. The authorities could not have known that they wanted to get married: it was all coincidence.

***

End of the line, please exit the train. Laila dives out onto the platform. We watch people jostling with their suitcases to get onto the escalators. It’s 16.25. “Maybe he’s landing right now,” says Laila. “Now my heart is racing.” We climb the stairs. “Ok… deep breaths.” She laughs, nervously. We go through the revolving door, past the airport cafes and restaurants. It’s now 16.30. Laila heads to the toilets. “Just to do my hair, it won’t take long,” she promises, apologetically. She’s back within five minutes.

How are you doing, Laila? “I’m good”, she says. “Good. Excited.” She goes on ahead, towards arrivals. We pass rucksack-laden people drinking coffee. She stops in front of the screen. The flight from Casablanca is fourth from the top in the list. Scheduled arrival: 16.20. Anticipated arrival: 17.10. Delayed.

Laila slowly makes her way back to me. We have a seat in a cafe and she orders coffee and cake for us both, and insists on paying. She looks at her phone. No message. “I’ll upload a picture to Facebook,” she repeats. “And I’ll mention everyone who has helped me. As soon as all this is over, I’ll write a thank-you letter to Mr Ott. Everything has happened just the way he said it would.”

***

After Toufik’s arrest, Alexander Ott invited Laila to his office to discuss Toufik’s legal options with her. Soon after, Toufik agreed to voluntary repatriation to Morocco. Once in Rabat, he applied for a new passport and wrote to the Swiss embassy in Rabat, applying for an entry visa. The reason given: marriage. The application was forwarded, and ended up in the Bern immigration office. The documents were verified and, on 12th October 2016, eight months after his arrest in Bern, Toufik received a letter: his leave to remain for the purpose of marriage. With immediate effect.

At 17.12, Laila tries to call Toufik on his Swiss mobile number. His phone is switched off. At 17.15 she goes back to the arrivals screen. ‘Landed.’ She comes back to the cafe, twists the ring on her finger, and glances nervously at her phone.

At 17.22 she can’t sit any more. She wanders around the arrivals hall. The screen shows that the baggage collection from the Casablanca flight has started. Laila navigates her way through the other people waiting, arriving at the yellow line. Her eyes flit here and there between the two doors leading into the arrivals hall. A woman with flowers comes through the door. A young man follows her and a group of people cheer when they see him. Laila waits. Comes back out from the crowd.

“Maybe they’re questioning him, even now”, she speculates. “The border police, I mean. Do you think they’re questioning him?” She doesn’t wait for my answer and goes back to her place at the front. A woman with a yellow suitcase, a police officer, and then a man in a wheelchair pass by. A woman embraces her husband, someone else waves as he comes through the door.

***

It’s 17.33 when she first sees Toufik, somewhere behind some backpackers coming through the doors. She lets out a sigh, steps over the yellow line and approaches him.

One month later, on 15 November 2016 at the registry office in Bern, the two finally exchange their vows.