By Ashley Archibald, Real Change

[Seattle street paper] Real Change hits its 25-year anniversary this month. The paper has come a long way from the publication that founder Tim Harris put together on his own in 1994, documenting the sweep of The Jungle, a homeless encampment nestled under the Interstate 90 and Interstate 5 interchange.

That sweep has played out no fewer than six times since the first publication. It might again. While the fundamentals of homelessness remain somewhat static — a lack of housing affordable to the poorest people in areas where they would otherwise have the highest likelihood of success in life — the paper dedicated to fighting it and empowering homeless and low-income people hasn’t.

For Real Change’s 25th year, founding director Tim Harris reflects on the past and future of the street paper.

So, 25 years after founding the paper. How old do you feel right now?

You know, it’s funny. I was thinking about that this morning. I used to say my internal age was 33, but it nudged up to 40. I think it’s this past year that’s put another 13 years on me.

I think a lot of people feel that way. Did organizing come first, or the idea to start a newspaper?

I had a foot in both worlds. I started my first newspaper when I was a junior in college because I knew how to typeset. I worked producing posters and flyers for student organizations, and since I knew how to typeset, I was audacious enough to believe I also knew how to create a newspaper. So, I started this thing called Critical Times, a monthly anarchist newspaper at [University of Massachusetts] Amherst.

So small press, largely volunteer-run newspapers was something I knew how to do.

Then I started organizing homeless folks in the late ’80s. It wasn’t until ’92 that it occurred to me I could combine homeless organizing and a newspaper. I was inspired by Street News in New York, which started publishing in ’89 and is regarded as the seminal paper in the modern street paper movement. It was the first paper anyone paid attention to that homeless folks were purchasing upfront to sell on the street. It took off like a rocket.

As an organizer, my dilemma was that I realized I had this value that homeless people need to be leaders in the movement against homelessness and their voice was critical to that and I was all about that leadership development. But I also realized that the horizon for economic justice organizing is very long and uncertain, and homeless people’s needs are very immediate and dire. So, the street paper idea appealed to me as a way to bridge that contradiction. That’s why I started Spare Change in Boston in ’92.

The idea evolved for me from there because the Boston paper was completely run by the homeless people that were involved in it.

I came to understand that wasn’t a workable model for what I wanted to achieve.

What I was interested in doing was creating something that would be a robust community institution that would be a voice of homeless folks. That’s what brought me to Seattle, to start over and not repeat the mistakes that I made in Boston and find a new way of doing this that would be more sustainable.

Why Seattle?

There was a robust organizing culture here. share/wheel was already doing homeless self-managed encampments, Operation Homestead was doing building takeovers, Street Life Art Gallery already existed, there were homeless people producing and selling their own art. There had been an attempt at a street paper called the Sea Town Crier. It, too, was homeless organized and suffered from the fragility of that.

Seattle seemed like a city that would be very receptive to a street paper and had all of the elements for public support that I was looking for. So, we took a chance and moved here.

What was homelessness in Seattle like when you moved here, and how has it changed?

When I got here, one out of every three homeless people was unsheltered, I was shocked by that because I was used to the Boston standard where unsheltered homelessness wasn’t really something that happened.

Looking back on it then, I remember those early One Night Counts when I got here being an overall number of 3,000 homeless people in King County and maybe 800 people that were unsheltered. I, of course, thought that was appalling.

When I look back on it now, that seems like some sort of golden age where homelessness was a relatively fringe phenomenon here.

That is really depressing.

It is depressing.

You have taken on the task of curating the archival pieces for the 25th anniversary [each issue of Real Change this year has included a ‘From the Archive’ section, republishing articles from previous issues of the paper, handpicked by Harris]. What has that experience been like?

I think of it as my memory-integration project.

Every time I go into the archives and I’m reading it I remember what the feel of that era was, who was involved in the paper then, the various volunteers we had writing for us.

Twenty-five years is a long time and it’s easy to be caught up in the present and for the past to feel very distant and disconnected in some ways. As I’ve been moving through the archives, I’m starting to see our history as more of a kind of a continuous narrative arch. There’s a Groundhog Day aspect to it because very, very similar fights just keep reoccurring.

With that amount of perspective, how has the paper grown and changed and the institution grown and changed? Did it go in the direction that you thought it would go, or has it branched out in interesting ways?

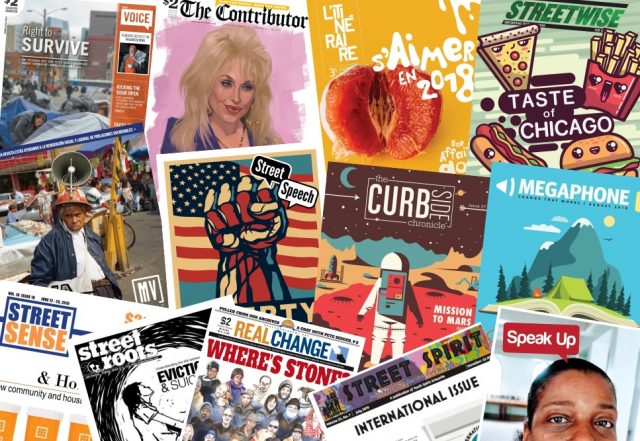

All along the way I’ve been very keyed into what other street papers look like and what the various models are.

Those can be summarized as the street paper as a vehicle for grassroots organizing, street paper as social services agency that does job training and connects people to services, street paper as a socially entrepreneurial business.

And Real Change is really much founded as an activist street paper that exists as a vehicle for organizing and as a way to elevate homeless people’s voices and the issues that homeless and very low-income people face. I think that while we have borrowed from those other models over the years, and that’s been part of our success, at the same time we have been very true to the vision of street paper as a vehicle for activism. It hasn’t been a continuous line. I think that progress seldom works that way. Sometimes you get two steps forward, one step back thing going on.

The point you brought up there was that this is about elevating the voices of homeless and low-income people. How do you characterize our relationship with the vendors, and how do you see the vendors?

I see the vendors as being the mainstay and the hub of a web of community relationships.

I think of each of our vendors are a hub of relationship unto themselves, and I see our vendors’ relationships to our community as being this kind of interconnected web. We have a number of ways that we involve the vendors directly in the organization. It’s always more than just selling the paper.

I think that’s where the heart of the organization is and where our highest aspirations are.

Something I think about a lot is that I think if you’d asked me in the first five years what Real Change was about at its core, I would have said we’re a low-threshold employment program and we are a vehicle for homeless and low-income people to be activists.

But I’ve shifted over the years to thinking that the most transformational thing we do as an organization is function as that hub of community relationships. That’s where the change comes from for the vendors when they feel valued by their community as a human being and respected as a human being.

It often changes their perception of who they are in the world and what they’re capable of and it elevates them. They start taking themselves on more seriously and often behaviors that they engaged in as adaptive strategies — numbing themselves with drugs and that sort of thing — that no longer squares with who they’ve become and they are able to move on from that. They take themselves more seriously as people.

They see themselves engaged in community that cares about them, they see themselves as having values. The public perception of who homeless people are changes as well. If there’s one thing we know, the most powerful thing about changing stereotypes around homelessness and poverty is proximity to the issue.

As people get to know our vendors, their idea about who homeless people are shifts as well.

I think in terms of culture change, in terms of our impact on community broadly, that is where we’ve had the most profound impact.

Do you miss anything about the early days of Real Change?

Absolutely.

I miss the chaos of it. I miss the constant multi-tasking I did in the early days.

For a short time, it was just me; I don’t really miss that at all. But when we were a much smaller organization with three, four, five people on staff and everybody kind of did everything and we were just there for the vendors and there was less of a formal separation between staff and vendors than there is now and more of a feeling of just being kind of one big, caring family.

I miss those days. I think we still have that to some extent, but it was lot more raw back then and much more immediate.

It also got very overwhelming. There was a time during our craziest point, around 2008, when we had something like 400 active vendors a month and half the staff that we do now. We were just frying staff people out back then like you wouldn’t believe. It was utterly, utterly unsustainable.

At the same time, with that sort of operating in crisis mode and running on adrenaline and taking on big things because it was the right thing to do even though we didn’t have the resources to do it, like when we did the campaign to stop the city jail it was in that period, when we were completely under resourced we took on this big campaign and ultimately were successful in stopping the jail. We took that risk because it was the right thing to do. The organization was all about the passion and the heart. But it was unsustainable. I think over the years we have moved towards sustainability and we have been able to maintain a lot of that passion and heart but it’s not quite the overextended constant adrenaline rush it used to be.

I suppose that’s both a good thing and a bad thing.

Looking forward, what do you hope for the organization and what do you fear?

What I fear most — and I don’t think this is going to happen because I don’t see that in who we are — is that we will become complacent. That we will take the easy route and kind of drop back and stay within our comfort zone.

I think it’s important for us to continually push our own comfort zone and grow and take on that challenge of being all about the vendors, whatever that means, and have the courage to be able to do that. I think that we are on a trajectory to be much more engaging of our vendors in an institutional way in advocacy than we have ever been before.

The thing about Real Change that is exciting to me — and in any street newspaper, really — is that there is this sort of platonic ideal that is a street paper that you never achieve that you move closer toward, that is this continual process of evolution.

I’ve seen that over Real Change’s history. We’re always evolving and asking how we can do things better but remain grounded in our authenticity as an organization that has heart and passion.