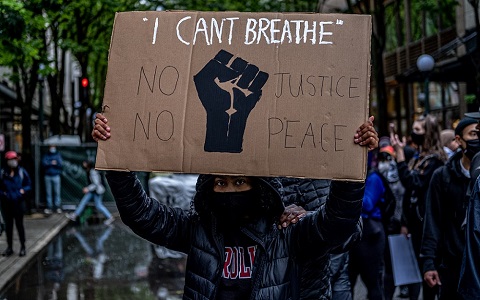

Portland, like many U.S. cities, has a public injection problem.

In Oregon’s largest city, public parks, playgrounds and walkways frequented by drug users are littered with hazardous used syringes.

People using intravenous drugs in public spaces are dying from easily reversible heroin overdoses. From 2011 to 2014, heroin contributed to a total of 284 deaths in Multnomah County, in Oregon, according to medical examiner reports.

Unsafe injecting habits are contributing to the spread of Hepatitis C and other blood-borne diseases and to public health costs. Acute cases of Hepatitis C in Oregon are 50% higher than the national average, with an estimated 95,000 Oregonians having contracted the disease, according to a 2014 Oregon Health Authority report. And half of them don’t even know it.

For these reasons, a coalition of organisations including Portland-based street paper, Street Roots, and Outside In, the nonprofit behind Portland’s oldest syringe exchange, is encouraging their local community to consider how introducing safe injection sites has the potential to combat these ongoing public health issues.

Supervised-injection sites offer a dedicated space for people to inject illicit drugs, which they have already obtained, under the supervision of trained medical staffers who are there to intervene with life-saving measures if anything goes awry. Staff also advise on safer injection methods and offer counselling and a connection to resources when a user is ready to quit.

Worldwide, there are 98 such sites operating in 66 cities, and peer-reviewed studies show they work.

Portland’s unofficial coalition of proponents banded together in June with New York filmmakers Matt Curtis and Taeko Frost to bring a documentary and open discussion about public drug injection to the city in an event called Safer Spaces.

“Opiate overdoses are wreaking havoc on people experiencing homelessness in Multnomah County,” Street Roots Director Israel Bayer said. “Street Roots believes that providing a safe injection site would help save lives.”

While homeless individuals make up less than 1% of Multnomah County’s total population, they accounted for 25% of heroin-related deaths in 2014, according to the county’s most recent Domicile Unknown report [the annual medical examiner review of deaths among people experiencing homelessness in the county].

Outside In director Kathy Oliver said her organisation participated in the event because it wants “to further the conversation about safe and healthy options for injection drug users in Portland.”

“Opiate overdoses are wreaking havoc on people experiencing homelessness”

The 34-minute Sawbuck Production Everywhere But Safe: Public Injecting in New York explores the dangers of public injection, both on the streets of New York City and on rural back roads in more remote areas of the state. [Watch the full film below.]

Curtis, the policy director at VOCAL New York, said the film is intended as a launch pad for discussion into how public injection is affecting each city where the film is shown.

“We want people to reflect on what this looks like in Portland,” he said.

He and Frost have presented the film and accompanying discussions in New York, Chicago, Baltimore and Seattle, where he said the most promising efforts toward opening a safe injection site are being made outside of New York.

Recently awarded grant funding will allow the filmmakers to bring their documentary to Los Angeles, San Francisco and Washington, D.C. They are showing the film only in cities where they have been invited.

The Portland public film screening was followed by a panel discussion about the possibility of opening a supervised injection site in Portland.

Sitting on the panel with the filmmakers and other health and addiction experts was Patricia Sully, an attorney and VOCAL Washington coordinator.

She’s been on the front lines of efforts to open safe consumption sites in Seattle and is a member of the Heroin and Opiate Addiction Task Force, a joint venture between King County and Seattle governments.

She said there has been expressed interest from county and city officials in moving safe consumption sites forward. The questions now are around funding and implementation. She said it’s likely Seattle will have multiple safe consumption sites co-located within pre-existing service providers, as users in Seattle are spread out throughout the city.

“We’re really on track to have a robust, sanctioned facility open in the near future,” she said.

Sully also discussed how advocates in Seattle are pushing for a site where it’s not only safe to inject drugs, but to smoke them as well. She said providing people who inject drugs with a place to use safely and free from fear of arrest, but leaving people who smoke drugs susceptible, could have unintended consequences that would perpetuate the disparity already present in the criminal justice system.

“All of our bathrooms have become shooting galleries for drug users. It’s not only unfair to businesses; it’s dangerous and inhumane,” Street Roots’ Bayer added.

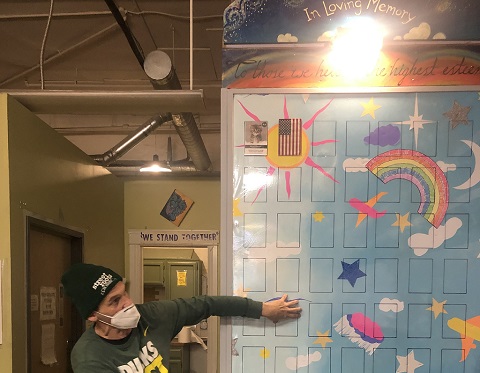

The Multnomah County Health Department does operate several syringe exchanges and a skin care clinic where intravenous drug users can get treatment for infections and abscesses.

But according to Bayer, current efforts are not enough. “Public drug use is at an all-time high in our community. Multnomah County has acted as a national leader in harm reduction for many years. Saying that, it’s time for the county leadership to step up and lead again,” he said.

Supervised-injection sites have been operating in many parts of Europe since the 1980s and in Australia and Canada since the early 2000s.

“Public drug use is at an all-time high in our community”

According to an analysis of dozens of studies on supervised-injection sites conducted by Ontario HIV Treatment Network, not only do supervised-injection sites reduce overdose incidence, fatality rates and injection-related disease; they also “lead to reductions in injecting behaviour and an increase in the number of clients accessing addiction treatment services.”

It also found these sites “do not lead to any significant disruptions in public order or safety in the neighborhoods where they are located.”

While the possibility of opening safe injection sites in New York, Boston, Seattle, Ottawa and Toronto is being explored, to date, there is just one such site in North America: Insite in Vancouver, B.C.

As the film Everywhere But Safe points out, after Insite opened in 2003, overdose deaths dropped by 35% in the surrounding neighbourhood, but in New York City, fatalities have increased 41% since 2010.

Within the first 12 weeks of opening, Insite was independently responsible for nearly 50% reductions in public injections, improper syringe disposal and other injection-related litter, according to a study by the Canadian Medical Association.

In another study of the same facility, conducted four years later by the University of British Columbia and the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, 23% of respondents stopped injecting before the study had ended and 57% had entered addiction treatment. 71% indicated Insite had led to less public injecting.

Curtis said policymakers in New York have been receptive, with members in both the state House and Senate showing support for legislation that would allow dedicated spaces where possession laws could be waived and establish a framework for county health departments to operate such sites.

He said hosting a film screening is a good first step, but it won’t work unless there is a sustained local coalition that continues to advocate for the establishment of a safe-injection site in each city where it’s shown.

Courtesy of Street Roots.