In 2013, the peer-reviewed academic journal Neurology published the findings of an Indian Department of Science and Technology backed study based on the idea that studying and speaking foreign languages have a positive effect on mental health issues. Dr Thomas Bak of the University of Edinburgh, and his colleague Professor Suvarna Alladi, looked closely at 648 people, of whom 400 could speak more than one language. The results showed that bilingualism could delay the onset of dementia by up to five years. Upon returning to his place of work, Dr Bak undertook more research into the subject, reviewing a further 262 bilingual older people in Scotland, with the findings further supporting his claim.

A year later, Robbie Norval, a 28-year-old from the Scottish coastal town of Troon (“the Sydney of the North”, as he tells me) came across the research. His gran had just been diagnosed with dementia, and after a stint qualifying and working as a solicitor, and then later teaching legal English in Germany and Sweden, he began working as a third sector advocate for people with the disease and volunteering at a care home. This perfect storm led to the germination of an idea.

“At work, I witnessed a lot of passive activities, like listening to the radio or watching TV which, though they sometimes increased well-being, didn’t have much of a positive cognitive effect,” Norval says. “Living abroad and learning languages really impacted my horizons, and soon after I started reading about art and music therapy and, at the same time, a lot of really interesting research began to trickle out about bilingualism and its effects on the brain.

“I got in touch with the University of Edinburgh, where the research was coming from, and asked whether it would also have cognitive effects over a shorter period of time, and it turned out that they’d actually done quite a few studies related to this subject in Skye, looking at learning Gaelic as a foreign language. So from all of that – my experience in the care sector, my gran and time teaching – I wanted to start an enterprise in the care sector that practiced good, fun, organic learning, but at the same time had a positive cognitive effect.”

From this perfect storm, Lingo Flamingo was born – a social enterprise that hosts classes, in residential homes and day centres across the country, teaching foreign languages to older adults as an innovative way of tackling dementia and brain ageing.

Now 32, and four years on from the establishment of Lingo Flamingo, Norval is speaking to me at their headquarters at the Pearce Institute in Govan, Glasgow, the day before students of Lingo Flamingo courses take part in a graduation ceremony. “I was never sure the concept would work. I was never a super ambitious individual. It’s always kind of funny, the stages, even though it’s progressing really well, and we have employees now, I always kind of wake up with worry that it won’t end up working out.

“It’s been a good journey so far, though not always easy. When we initially went out to care homes with this idea for language learning some laughed in our faces and said ‘why the hell would we do that, they’re 85 and have dementia’. We’ve had to work on that a lot, on taster sessions and working with the research team to show the impact of it and getting feedback. A lot of our social impact and credibility comes from the research, but we’ve now built ourselves up and done over 700 courses in the last two years, so now we’re known in the sector.”

INSP: I was going to ask what sent you down this road but, as you’ve touched on, there was a personal hook there with your gran.

Robbie Norval: To me it seemed totally natural to get into the social sector. I understand why society is profit driven but, and I guess I’m quite left on the political spectrum, I just see that it’s such a good service, making something which has a social impact as well as being sustainable is a really great thing to have, measuring your footprint not in terms of money but in terms of influence and impact on society. I have a good friend who has an architecture firm in Glasgow, it’s quite a social minded business. As I was mulling it over, we talked about the model and it really suited my ideals, and the mission as well.

What about the logistics of Lingo Flamingo? We know about the overarching goal of the project, but how do you actually deliver on a micro level?

For us the educational side of it on a class by class level is a bit burdened, and so it’s something we really have to overcome. These are people who left school at 12 or 13 years old in the 50s and 60s, and you’ve got to remember that they may have got the belt for making mistakes, and left when the school system was a lot different to what it is now. Their only language experiences probably revolve around some very grammar heavy stuff – Latin and ancient Greek, for example. There’s a bit of a perception that they’re either too old or too dumb to learn a language, from their own perspective as well as wider society’s. But we want to challenge that. Language learning is not about perfection. It’s about having fun, and the inter-cultural element, breaking down barriers about different nationalities, or stigmas or stereotypes. We spent the first eight months of the organisation doing a lot of focus groups with Alzheimer Scotland in different care homes and local organisations to find out what people wanted to do.

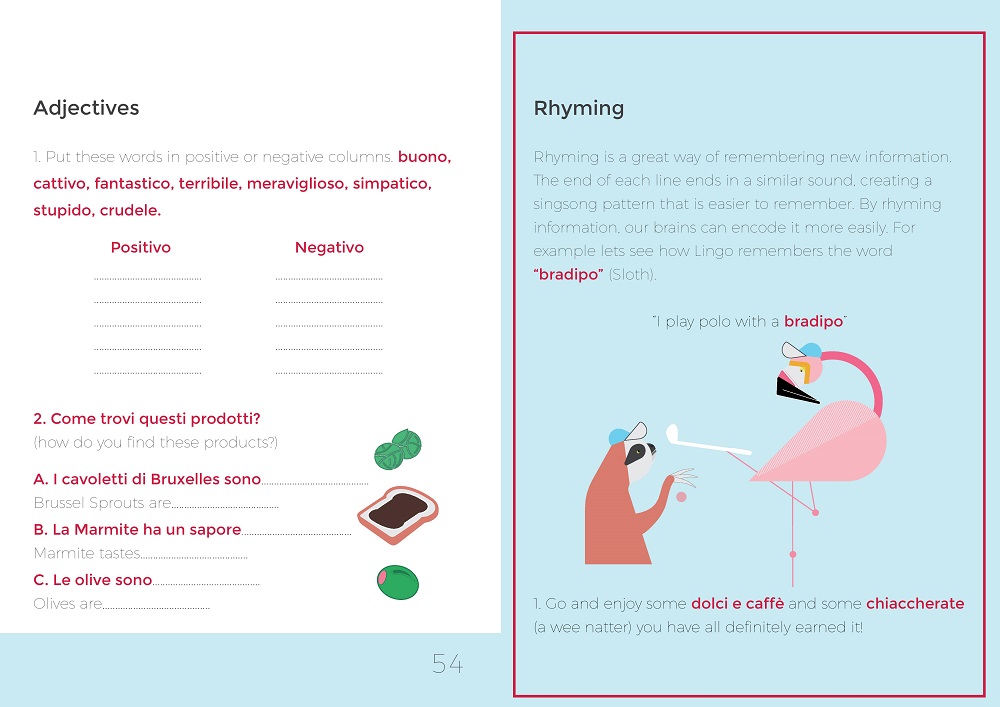

We started to tailor language workbooks with larger fonts, incorporating a lot of memory techniques. This not only helps them memorise vocabulary, to help with the language learning, but also develops skills that they can utilise practically, to help remember when and what medication to take, or when visitors are coming. And we also made it very time appropriate, using references that work for them, and also using sensory stuff, to do with taste. For example, you could have an Italian class where you’re cooking bruschetta together, feeling the dough, putting tomatoes on top, learning the words that go along with it and at the end you have a product you’ve made yourself, so there’s even more of a sense of achievement even before the language takes hold. A lot of our social impact comes from challenging the stereotypes of dementia. We’re certainly not saying that class members would be fluent in a language after a course. But even if they remember a few new words, it’s really nice to see their sense of purpose, and they think to themselves, I have retained this information despite my diagnosis.

The specifics of the classes depend on the ability of the older adults involved. Day centre members tend to have a slightly higher cognitive level, whereas with care homes you’re working with people who have early on set dementia and, in some, more advanced forms of the condition. And we work with people who have Parkinson’s and those who are non-verbal due to suffering a stroke, so what we try and do is just make things as accessible as possible. We’re still learning a lot about people with different disabilities, and how these language techniques affect them. I definitely wouldn’t say that we’ve got a course which is perfect for everyone, but we do our best to try and achieve that.

I didn’t realise that the classes took on that physical element quite so profoundly.

Yeah it really works well. We had a nice project recently, in [Scottish seaside town] Largs, where the tutor had the idea of writing to a care home in a twin town in France. Each care home began to write postcards back and forth to each other, again allowing the attendees to relate to someone else in a similar position, but in a different country, and making it a fun process as well. Our techniques make for a lot of fun stories and banter. Some people think older adults are just really polite and stoic, but they also just want to have fun and there have been some great tales.

What about the science behind it, how much can you tell us about that?

Obviously I’m not a researcher, so we work quite closely with the University of Edinburgh. The way they measure the effectiveness is through a frequency test. As expected, initially people under 30 perform better, as there’s no ageing brain as such. Between tests, they take part in the language learning classes and, after taking the test for a second time, although for all parties there’s cognitive improvement, the biggest jump is in the older adults, the kind with which we work. They have a lower baseline store initially. Even though the younger adults may go up in terms of maintaining the information of the language, the cognitive levels go up for the older participants.

If you’re doing a Sudoku or a crossword, there’s this belief that they’re really good for you. I’m not advocating that they’re bad for your health and brain, they do some good, but it’s quite simplistic. You’re putting what’s already in your brain on the paper, but you’re not taking in any new information. Whereas with languages, you’re speaking, writing, reading, listening, communicating – all your senses are being engaged. You’re in a situation where you’re building up a second library of words in your head – what we call a cognitive reserve – and building that up makes our brains more resilient. The more you do this, the better it is for your brain. It’s a workout for your whole brain, rather than a puzzle, which focuses only on one part of your brain. Language learning is a real mixture.

What languages do you focus on, and is there a difference in how effective certain languages are?

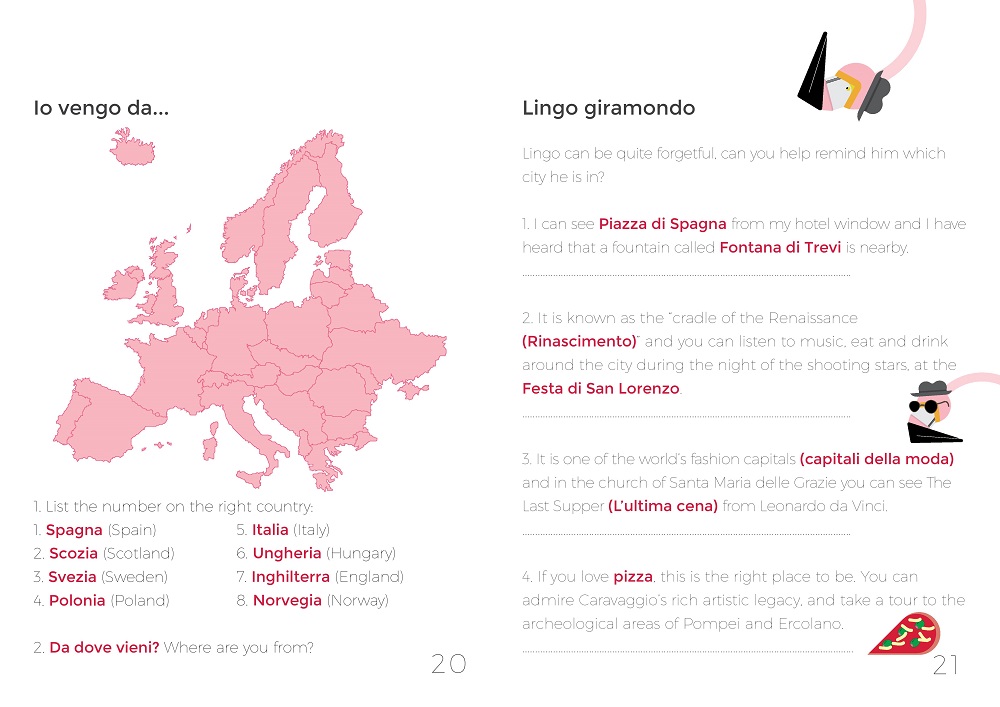

Spanish, Italian, French and German. The main ones are Spanish and Italian. German we have a little bit of difficulty with, as older generations have certain negative perceptions about Germany that are engrained, mainly because many of them lived through the Second World War. But actually it’s sometimes really nice because, like I said, part of our mission is busting those stereotypes. I remember hearing in one class, a student said to the tutor, who was German, “oh you’re really nice for a German” and she replied “how many Germans have you met?” and he said “None!” So that shows you the mindset. I do like hearing that because it shows that we are breaking down the stigma.

So you go into care homes and host the classes there, all over Scotland?

We go to care homes, day centres, or in conjunction with Dementia in the Community and Alzheimer Scotland, organisations like that who have resource centres. It works like an outreach programme. And we operate all over Scotland, from Aberdeen down to Ayr. Later on this year we’ll be opening our own small community hub and host in-house classes in the south side of Glasgow. That would be a bit different as we’d do our usual older adult classes, but also we’re planning on branching out to help with our sustainability and income, with classes for kids and their mums, and hopefully some pro bono EFL classes, which is exciting as hopefully that will help us be sustainable in the long term.

I guess learning a language is good for you regardless of what age you are or whether you’ve developed cognitive difficulties or not. How important is it as a society for us to learn languages, to ensure we’re developing our cultural intelligence and, as the research behind your work suggests, so our brains function at the maximum level that they can?

I’m always quite biased when it comes to questions about the importance of language. But I think the research is really interesting and backs this up. Language learning was very stigmatised for a long time and, for people being brought up in the 70s and 80s, who had a parent from another country, it was really frowned upon here for them to be brought up in a language other than English. Because back then people felt, wrongly as it turns out, that the brain could only hold a certain amount of information and they thought, by learning a second language, it increased the chance of things like schizophrenia and depression in your child, which obviously is nonsense. So, especially over the last 15 years, there’s been some really positive research about language learning being positive for your development and for increasing concentration and perception skills, and also gives you better emotional intelligence because you can link a language to certain individuals – for example, extremely young children are very clever about knowing they can speak to one parent in one language and the other parent in another. Even the inter-cultural elements are important, just to see people as they are and not to judge them on perceptions or how the media portray them.

I used to live abroad and observed how the importance of learning English, and even other languages, was drilled into people from an early age. We just don’t really have that here; it’s not as engrained in our culture.

Yes, and also here we deal badly with the fact that we know everyone speaks English everywhere too. In fairness to people in the UK, I understand that it can be frustrating for learners here to go abroad, to try a language only for the person to reply in English – it can be quite disheartening. But for us at Lingo Flamingo, we really advocate the health benefits. Regardless of your ability to learn a language, merely trying is really good for the brain and is a thorough workout.

Do you find yourself to be quite an entrepreneurial person?

Not really to be honest, that’s certainly something I’ve had to give myself a push towards, not in terms of becoming more commercial, but in terms of becoming more sustainable through private sales and stuff. But being more entrepreneurial in that respect is a great thing. The more you can generate your own income, the more grants funding that becomes available for different ideas, different charities, so I have come to a bit of a realisation that ‘selling’ isn’t always a dirty word, so certainly I’ve have come a long way from my original thoughts.

At the Social Enterprise World Forum (SEWF) [which takes place in Edinburgh in September, and to which Norval has been invited as a speaker] you are involved in a session that’s to do with how you create market opportunities in the social enterprise sector, so does that kind of tie in with the fact that you’ve come to understand more about that part of it over time?

That’s what’s quite exciting about being involved. I’m not a natural entrepreneur, and I get to talk about my journey and having an idea. I guess the problem with social entrepreneurship, a lot of the time, is that people have an idea and struggle to make money off it, so I’m probably someone who had quite a good idea, and has grown from getting a lot of funding help to edging more toward the private sector. So even though it’s not necessarily my passion, it’s definitely something I’ve learnt a lot about through being involved in social entrepreneurship.

What’s your experience been of the sector itself as a whole? Do you find that there’s still a stigma attached to the idea of a social enterprise, do you have people still asking you ‘how do you make money’? Have you found yourself coming up against that wall?

There can be a bit of a stigma towards organisations like us that are kind of between being a charity and a business. Although, Scotland is one of the most progressive countries for social enterprise. In many other countries it doesn’t really translate – on a language level as much as an understanding level. They may not have a specific word for it, they just translate it directly, so it’s interesting that it doesn’t quite exist as solidly as a concept. You’d have to explain it a bit more, whereas in Scotland the vocabulary of social businesses is far more well known.

Scotland is an interesting case. Often we have quite right wing governments but left wing cities, especially Glasgow. It’s a niche area. In countries in Scandinavia, the state takes on a lot of responsibility, so there aren’t as many cracks to fall down into. It’s interesting that Scotland is in a more pivotal situation regarding social businesses.

It doesn’t matter what your political views are, Westminster hasn’t put a lot of money into social enterprises the way the Scottish Government has. Even that is a way in which it’s been promoted – as a government policy in Scotland. In some countries they certainly have very good tax breaks for businesses, like Canada, and so they do have a promising social entrepreneurship environment there. But I’ve heard that they do look to Scotland as an example.

It’s certainly thriving here. Flexible working has had an influence. I really like the fact that 60 per cent of social enterprises are run by women; comparing that to the business sector, it’s almost three times as much. So it does I think give you more flexibility as a business model – home working, flexi working. The pay certainly would be less compared to the private sector, but your self-esteem and self-worth is improved. That’s maybe why it’s been such a success and it’s grown.

With the SEWF coming here, what does it mean to you to be asked to be involved and what’s the significance of it being here?

It’s a real honour and exciting. I was so surprised, especially seeing some of the other names, but when I speak I’m quite an honest speaker, and I like to not just look at it all with rose tinted glasses. There are challenges and issues but I think as a movement it’s such an important thing. Just at its principle, the business is driven by the impact and that’s what our society needs. We live in a society where the rich continue to get richer, and I think it’s so refreshing to have a business model that’s about the impact on people rather than money driving it.

When I saw the category I was speaking in, I kind of had a chuckle as that wasn’t initially my forte but I’ll certainly do something with it, and it’ll be about the journey and the improvements I’ve made on that subject. In fact, it is actually even better to talk about things that we’re currently learning about and improving in.

Do you think what you do at Lingo Flamingo grabs the general public’s imagination more than other social enterprises, in terms of understanding the goal?

We’ve been lucky with making sure we have nice branding, the imagery is engaging and linguists volunteer for us as tutors because they’re excited about the message of accessibility of language. Sometimes it can be a bit snobby, talking about how many languages you speak, but for me it’s much more about giving it a shot and showing it’s never too late.

We’ve had a lot of good media coverage and I guess from the outside looking in, the concept might seem a bit wacky, but once you grasp it, it does start to make sense.

When there are particularly dramatic stories of how the classes have worked, that can be something that really draws people in on a personal level. My favourite story is about a woman called Jean and her husband, Robert. She was learning Italian, and she said: “Robert’s usually a crabbit old bastard, but when he becomes Roberto, he’s fabulous”. Life shouldn’t be taken too seriously.

The other side of the coin was a woman who was in a care home in Ayrshire who used to be a librarian. Her husband still lived at home and she had quite bad dementia, having been non-verbal for quite a few months. She sat in on classes, and in some cases attendees don’t actually speak they just sit and soak it up. And maybe after the fifth class she finally said out loud “Ciao”. In the final class of the programme, she picked up a pen and wrote it down, which was the first time she had written something in around two years. Sometimes the smallest things make a huge difference. I like to think our classes balance the confidence building and fun with the really serious cognitive improvement and that can be huge for them and their families.

INSP Members can download this article from the INSP News Service here.