By Michael Gasser, Surprise

Swiss artist Eva Borner’s latest photography project reveals the sleeping places of homeless people in Athens. Shocked by the increasing numbers of people sleeping rough in the Greek capital, Borner set out to document their lives – with a little help from Shedia vendor Michalis.

On your Facebook page there’s an “I love Greece” picture that someone has commented on saying “Greece loves you too”. What is it that ties you to the country?

I’ve visited this country regularly for 25 years and I’ve lived in Greece for four years, at first in Santorini and then in Athens. Over this time I’ve made some good friends.

The basis of your photo and video work is the exploration of the aesthetics of absence. Your latest work depicting the sleeping places of the homeless shows no people. Why is that?

I feel that it’s more open: the viewer has the opportunity to place themselves in the situation – without being self-conscious. My current project “invisible people/if I know where I’m staying” goes back to my last stay in Greece. I was shocked by the ever-increasing number of homeless people.

According to the Greek NGO Klimika, there are 15,000 homeless people living in Athens alone. This figure is said to have quadrupled between 2013 and 2015. How has that affected the city and the people living there?

The atmosphere in Athens is tense. You can tell that the country is suffering from the relentless austerity measures. To a large extent they’ve broken the social infrastructure. Everyone is worried about money, my friends included. Even those who are well-educated. An economics professor, for example, now – like so many others – only earns a third of what he previously did, even though prices are steadily rising.

Where do the homeless live in Athens?

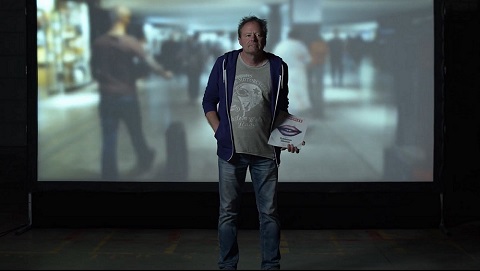

Last winter I found evidence of people living in the gaps of walls. I contacted the Athens street magazine Shedia to find out more. I wanted to participate in one of their city walks guided by the homeless. I was put in contact with Michalis, a former aircraft engineer of Olympic Airways that was privatised in 2009. He had studied in the US, spoke perfect English but now lives in a men’s hostel. He introduced me to the homeless world.

Did you hesitate in photographing the sleeping places of the homeless? Is that ethical?

If I were in the situation myself I don’t know how I would react if somebody photographed my personal space. I admit that. But Michalis was of the opinion that it’s essential to make people notice the homelessness in Greece and document it. I took this to heart and tried to look more closely. Thanks to my encounters I quickly became aware of which people I could approach and which I couldn’t. I talked with the people and asked them if I could photograph where they slept. Although I didn’t know at the time whether and how I would use the pictures. But they all allowed me to present their situation in my work.

Have you also met any homeless women?

According to Shedia, 30 percent of the homeless are women. But I must confess that I’ve not met a single homeless woman in Athens in nine months. It surprised me how well educated the homeless people I met were. All of them spoke excellent English. During the talks I realised just how little it takes in Greece to end up on the streets: lose your job, can’t find a new one and already two or three months later some people lose the roof over their head as well.

What’s revealed by focusing on the belongings of the homeless rather than the people themselves?

I wanted to protect the homeless during the process. Their situation shouldn’t be ruthlessly public. And I think that the sleeping places alone can say a lot. So I never noted down the exact names or stories of the people.

Did you stage the photos in any way?

No, I just photographed the situation exactly as they presented it to me. In total, I photographed around 50 sleeping places. And I always felt great respect for it. Gradually it occurred to me that the homeless consciously select their places. They were often beautiful places, characterised by striking graffiti or great posters. Generally, the places were also clearly visible. By being open to the public the homeless wanted to protect not only themselves, but also what little property they have.

Have you encountered any of the homeless people again since you finished your work?

I would have liked to show the pictures to them but all but one had already moved on when I next visited. Where to, I don’t know. Maybe I’ll find out this winter when I travel back to Greece.

Translated from German by Leighton Jacobs.

INSP members can download this story from the News Service here.