By Katherine Haines

Every day, about one pound of food is wasted for every person in the United States alone, over 133 billion pounds, which is about 30-40 per cent of the food supply that goes to waste every year. Food is the single largest category of materials put into municipal landfills that emit methane. This equates to about one pound of food wasted per day for every person in the country.

The US had a high rate of food waste even before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as supply chains struggled to shift when COVID-19 forced many restaurants to close, and panic buying cleared off store shelves, food waste became an even more visual problem.

News coverage capturing graphic incidents of food waste at the top of the food distribution chain, like animal euthanasia and milk-dumping at farms, drew explicit attention to the food waste issues in the harvesting, processing, and distribution systems that manage and transport all of our food.

While it’s clear many of the processes surrounding our food need re-evaluated, especially in another wave of shutdowns, food waste is still something mostly exacerbated by consumers. If anything, the shutdown of restaurants points to an issue of how people consume food. Beginning in March, spending at restaurants and hotels declined by more than 60 per cent due to COVID-19, and grocery spending increased by 70 per cent and continued to increase by 10 per cent through April, May, and June of 2020, pointing to the fact many households relied more on prepared food from restaurants than cooking every meal themselves. But what happened to the food caught in the middle?

Food recovery/rescue programs

Most people associate food assistance organizations with the idea of a food pantry, a place relying on donations from individuals in the community or from grocery stores. However, many organizations with food assistance programs also have food recovery/rescue programs in addition to accepting donations.

Even before COVID-19, We Don’t Waste – located in Denver, Colorado – was, and still is, a non-profit organization focused on food recovery and rescue. Communications and advocacy manager Allie Hoffman discussed the motivation for the start of the nonprofit in 2009. “The need is huge for food, and the need is also really huge for food recovery because there’s a lot of really good food in the US and globally, but especially in the US, that ends up in the landfill,” says Hoffman.

We Don’t Waste now runs with four large refrigerated trucks and an 11,000 square foot distribution center with walk in coolers, and soon-to-have walk in freezers as well.

“We like to say it’s not a warehouse because we don’t want to warehouse food, but we’re able to take large bulk items you can’t necessarily flood the community with – because it’s something like 13 palates of black pepper – so we’re able to portion it out and get it out to the community as it’s needed,” says Hoffman.

![Farmers to Families Box Contents - Local produce wholesalers unable to do business with commercial food vendors and restaurants during the pandemic have generated revenue by selling food boxes to the USDA Farmer to Families program. [Courtesy of MontCo Anti-Hunger Network]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/INSP_The-connections-between-food-waste-homelessness-and-COVID-19_9-1.jpg)

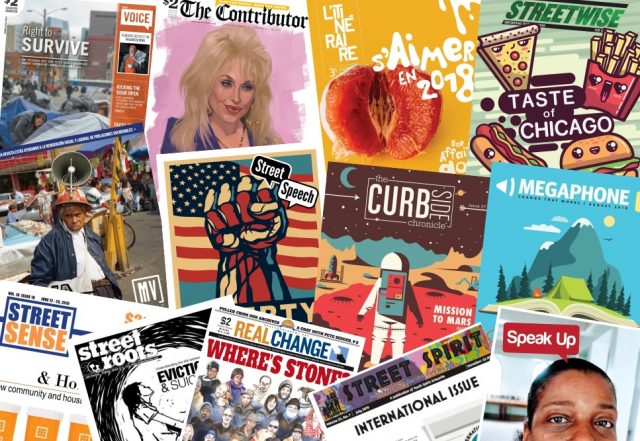

We Don’t Waste focuses mainly on large-scale producers, distributors, and venues whereas another organization, The Stewpot, located in Dallas, Texas, also has a large food recovery program, working primarily with restaurants and more local businesses. The Stewpot’s food recovery program is part of a larger project for social good, as they offer services like mental health counseling, relocation help, ID and housing assistance, mail services, and many different classes and workshops, in addition to running their own street paper, STREETZine.

Rob Guild, manager of food recovery for The Stewpot, constantly reiterates that there’s no donation too small. He uses the ‘stone soup’ metaphor when looking for donations: “I grew up with this story called stone soup. I’m going to bring these rocks and then you pour water over them and then all the city people are like ‘hey what you got there?’ ‘Oh it’s stone soup, but you know it’s better if you have some salt and pepper.’ ‘Oh well hang, on I’ve got some salt and pepper,’ and that person brings some salt and pepper… and then one other person says ‘Oh well I’ve got this…,’ and then the next thing you know the whole community is gathered and they’ve built this cauldron of soup. They all eat it because they all participated and that’s the idea we’re trying to foster.”

These organizations help to recover food waste after production and/or distribution, and continue to during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, most of the food assistance programs and organizations across the country have had to shift their approach to both taking in food and getting it out to their communities.

Adapting to COVID-19

Throughout the pandemic, 19 per cent of American households reported no change in their eating habits, suggesting many US households experienced some kind of effect on their access to food. While the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) hasn’t gathered its yearly data for 2020 yet, many experts predict from the rise in unemployment and increased use of food assistance programs that many more households have struggled to maintain food security during the pandemic.

The Stewpot recovers food from restaurants and local businesses to feed people cafeteria-style, but also to distribute to the community. Guild says, before COVID-19, The Stewpot held one food distribution week a month that people could sign up for online and then come put up free food for their families. Now they hold three weeks of food distribution a month and serve between 130 and 150 people a week, compared to about 100 a week before COVID-19. The Stewpot also expanded their food servicing to make and donate meals to the 500 homeless people a night who were being sheltered in the Dallas Convention Center.

However, they have had to adapt their strategies in serving the community in order to stay safe. Their food distribution weeks are now drive-throughs, and there have been significant modifications to their cafeteria approach. They now use single-use trays, cups, and cutlery rather than reusable ones, have cut the amounts of chairs at tables, and space out the line to meet distancing guidelines.

Similarly, We Don’t Waste has adapted by doing no-contact deliveries both in getting the food to the organization and in getting it out to their community partners. We Don’t Waste has also increased the number of their mobile markets from two to eight during COVID-19 and transformed them from a farmers-market style to a drive-through contactless mode.

These organizations focus on recovering and relocating food that has already been produced and/or distributed, but the COVID-19 pandemic also challenged the food producers themselves.

Adapting to a broken supply chain

When restaurants had to close, producers and their distributors lost an entire market where they sold food. Some of that food could be shifted into grocery stores, but not all of it. To try and help farmers and households, the USDA organized the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and Farmers to Families food box program as part of the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program to purchase food from farmers and distributors and send out those agricultural products to people in need through food-banks and other community-based organizations and non-profits.

Executive Director of MontCo (Montgomery County) Anti-Hunger Network (MAHN), Paula Schafer worked with the Farmers to Families food box program to distribute it to the community and the foodbanks in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania.

![Direct to Food Pantry - Over eight weeks in July and August of 2020, MontCo Anti-Hunger Network delivered 22,424 boxes totaling 272,296 pounds and valued at $393,328 to community food pantries. [Courtesy of MontCo Anti-Hunger Network]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/INSP_The-connections-between-food-waste-homelessness-and-COVID-19_8-1.jpg)

“The farmers to families box program was designed to give some economic relief to those business owners who all of a sudden had no place to sell their food,” explains Schafer. “The idea was to circumvent the market they normally sell to altogether and box their product in a way it could be used by households, then we were challenged to establish a distribution network to get those new boxes being put together by food vendors to people who needed the food assistance.”

The program partnered with distributors (national, regional, and local) to purchase up to $4.5 billion in products like fresh produce, dairy and meat from American producers and farmers.

MAHN works as an umbrella organization in Montgomery County to help organize and coordinate 43 different food pantry and food bank organizations serving the community, especially as they lost many of the volunteers because of being in the at-risk age group for the contraction of COVID-19 (as did many other food assistance organizations around the US).

MAHN coordinated the large-scale emergency donations from donors like Hatfield and Chobani that were used as supplementary donations, while they weren’t getting donations from grocery stores or individuals in the community. MAHN also coordinated a two-part Farmers to Families box distribution. The first leg of the distribution project included five large-scale events that facilitated direct to community Farmers to Families food box distributions occurring between May and June. During this time, MAHN gave out 25,500 boxes totaling 378,750 pounds and valued at $706,965. For the second leg of the project, MAHN worked with Lansdale Warehouse to do direct to food pantry distribution of Farmers to Families boxes for eight weeks. During this time, they donated 22,424 boxes totaling 272,296 pounds and valued at $393,328.

We Don’t Waste also received donations through the Farmers to Families program, like dairy and meat, and were able to distribute it to their community partners.

Schafer says the Farmers to Families boxes were “an opportunity for people to get food without having to go to a food pantry because, all of a sudden, people who were unfamiliar with how food pantries operate or how to even access a food pantry were in need of food assistance, and so we were trying to circumvent all of those obstacles that kept them from getting food.”

![Direct to Community - MontCo Anti-Hunger Network direct to community distributions of Farmers to Families food boxes in Montgomery County PA occurring during May and June of 2020. During this time, 25,500 boxes totaling 378,750 pounds and valued at $706,965 were given away. [Courtesy of MontCo Anti-Hunger Network]](https://hub.insp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/INSP_The-connections-between-food-waste-homelessness-and-COVID-19_7-1.jpg)

On the bright side, we’ve learned what things work

There is hope that a pandemic pointing out our severe failures in food distribution may encourage people to find solutions.

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed how food assistance organizations like food pantries and food banks have interacted with their communities. Schafer from MAHN said three of the 43 pantries in their network have the capacity to do online food ordering, which they were able to really rely on and even expand the client base they served during the pandemic.

Guild praised the extra safety precautions necessary for protection, but he also likes the idea of keeping it around post-COVID as just another layer of safety for his staff and those they serve.

He also said more of an awareness, about what people can do with their food rather than throw it away, came from people having to look at massive amounts of food and having nothing to do with it, but not wanting to dump whole kitchens worth of food. People saw the inherent value of donating food that hadn’t even been prepared yet. In reaching out to The Stewpot, restaurant and store owners were able to learn not only could they donate food that was unprepared and in excess, but they could also donate prepared food too.

“It put our foot in the door of a lot of places, conversations we never would have had, restaurants that never would have contacted us, thinking ‘throwing this stuff away is the cost of business’ but it doesn’t have to be,” said Guild.

And learned more about each other

Schafer praises those in the MAHN network saying, “Food pantry operators are resilient and they can roll with the punches and they never stop rising to the challenge to make sure people were getting the food they needed. It was really pretty amazing.”

Perhaps the best thing we can learn from this though, is more compassion and understanding for others, especially those less fortunate. Guild, and many others, have noticed COVID-19 has brought more of an awareness, as it has been an equalizing force that has shown people how easy it is to find yourself in a place where you need help. While COVID-19 hasn’t affected people in all the same ways, it has shown many it doesn’t take much to become that person you looked down on in the line for food at the food pantry, or someone who loses their home or their job.

“It’s not just people who are ‘lazy’ or people who ‘just want a handout’, some of these people are sick, some of these people are hurt. And it’s our job to help people who need help, there’s more than just being a decent human being. If I was hurt I would want somebody to help me. They’ve got nowhere else to go, they’ve got nowhere else to be, and maybe they can’t do anymore. This is as good as it gets,” says Guild.

Guild knows sometimes it’s hard not to judge people that don’t appear like they need help, but COVID-19 changed everyone’s situation across the board. Guild said one thing he’s noticed is a relaxation of the stigmas around people needing help.

“It’s easy to look at a homeless person and see the homeless and forget the person, that’s incredibly common,” Guild says, but now, the pandemic has made it not so easy to distinguish between people that need help. “It’s really easy to hide behind that excuse of ‘well they’re all just homeless people and are going to keep being homeless people anyway,’” says Guild.

There’s more to homelessness than “just some dude on the street”.