When Neil McInroy, the CEO of the Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES) and the second keynote speaker at the 2017 Global Street Paper Summit, appears at Manchester’s Bridgewater Hall kitted out in a dark mustard corduroy suit, trendy clear frame glasses and a disheveled Morrissey-esque quiff, something in my brain doesn’t quite compute.

When he gets on stage and starts to speak, bounding about like the frontman of a rock band, I’m even more confused. Economics is dry; economists are straight-laced, buttoned-up, and serious. They are not supposed to be entertaining. They are definitely not supposed to be cool.

But after listening to the Manchester-based champion for social justice and a progressive economy, it is clear that his eccentricities, his humour and his ability to engage are part of what is making people sit up and take notice of his cause. As he tells delegates: “We have an amazing array of crises. We need to remember that the economy is not distant and sterile; it is part of our homes and our hearts. I’m an economist, but I’ve went a bit weird.

“I’m a polygamist: I am married to economic development and policy, but I’m actually in love with the alternative, the disruptive, the punk, the hippy, the difference. Our job is to try and infect the mainstream with that.”

When we sit down afterwards, he tells me that he is a bit of an outsider within his community. “Being that way isn’t common in the public policy and economic development world. There’s a soberness to it, and so personality, passion and human emotions are seen as a distraction from the empiricism of economic development and place economy. But of course if we believe that an economy is about what people in places want, then obviously the economy, and the people who think and talk about the economy, need to be imbued with raw human emotions too.”

And even if people within that community do believe that he, and his organization, come from a particularly “odd space”, McInroy is happy to embrace it. “Arguably, part of the problem we’ve had in the economy as a discipline is that it is seen as a science that has created its own objectivity and neutrality. The economy needs to be imbued with a spirit and a notion of what human beings are all about. I think people would see us as maverick, out of the ordinary, in terms of an economic development, public policy organization, but they also see that the great quality work we are doing can unlock quite wicked social issues.”

Talking to McInroy, it seems as if he has been instilled with this passion and spirit his entire career. It is quite a contrast to the summit’s previous speaker, social epidemiologist Richard Wilkinson. Both focus on social inequality, and neither is more fervent in their work than the other. But while Wilkinson’s work seems more measured and restrained when delivered, McInroy is emotive, explosive even. “I suppose personality always comes through in my work. I had a realisation that it’s not enough just to give a message or write reports which slot into the convention and the mainstream, I think you also need to agitate and be disruptive.

“I suppose there’s a tactical consciousness of actually being demonstrably different to unlock some of the issues we have in economics and economic development, because isn’t disruption a great way of starting to expose some of the problems there is in a particular situation? For there to be a renewal, you need to actually appreciate the problems of where you are. And I think that needs an element of disruption, controversy, discord.”

If we believe that an economy is about what people in places want, then obviously the economy, and the people who think and talk about the economy, need to be imbued with raw human emotions too.

CLES describes itself as an independent ‘think and do tank’. It’s clear that while the ‘think’ is arduously worked on behind the scenes by McInroy and his colleagues, the ‘do’ is to very explicitly incite people, such as the street paper delegates in the audience as McInroy gave his keynote speech, to continue their work in trying to make a structural change that will move the economy in a more socially just direction.

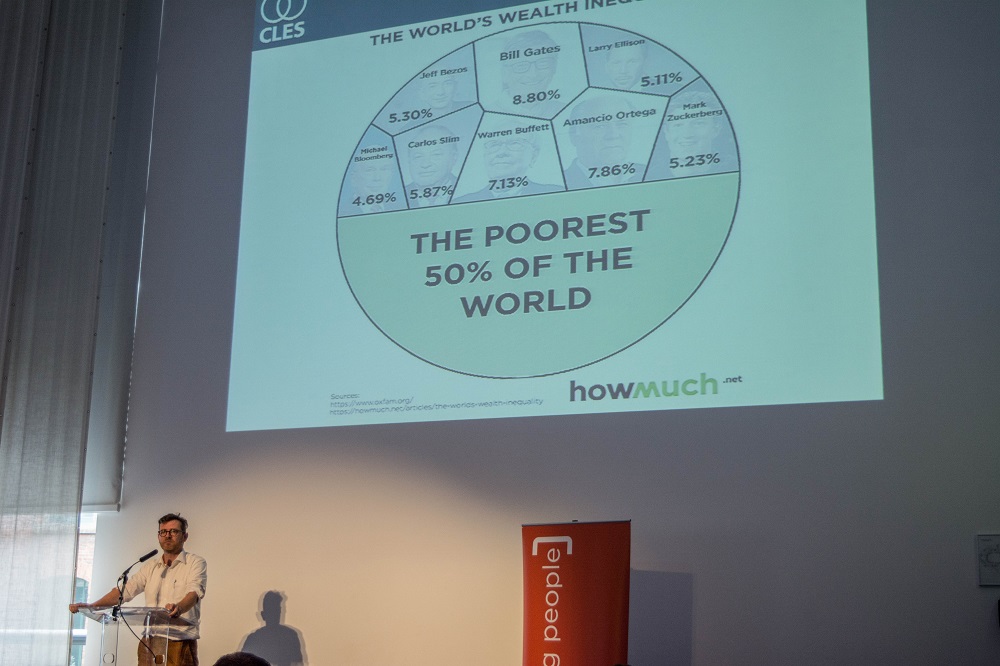

During his speech, it is difficult not to be roused by McInroy’s very direct way of laying out some of the issues local economies are faced with in the modern day. He describes the fact that GDP is going up, and poverty is increasing with it, as “madness”. He bemoans geographical divides, an over reliance on philanthropy, and exclaims: “the system is rigged in favour of the large”.

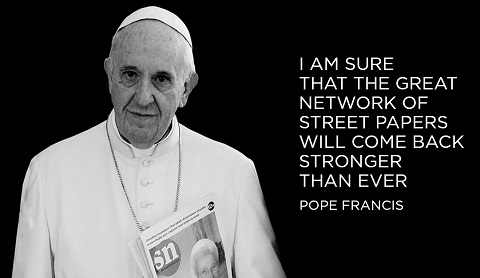

However, capping this off is his utter admiration for street papers. “We’re seeing a new social flourishing that can tackle the problems of our economy and create and even better world. Street papers are part of this – and age of experimentalism that is changing society.”

In private, he delves further into this line of thought. “There’s the traditional role of street papers in terms of communication and information and that’s important. They actually raise and increase the profile of homelessness and they’ve done that to great success. But what’s important is the ripple effect street papers have.

“Street papers are fundamentally about social change because they’ve gone beyond the individual, beyond the community. It’s actually a space, both in terms of the paper itself and the organization. It’s a space where you’re exploring and trying to understand and address sets of pernicious social issues.

“Street papers do not just represent a transaction between the vendor and the buyer. Actually what you are engaged in is a relational act to look at the broader relationship that a street paper has with place and how it stimulates a whole range of possibilities in terms of what might happen socially and economically.”

Perhaps crucially, considering McInroy’s straddling of the conventional and the alternative to communicate his message, it seems that his work, and that of like-minded individuals at CLES, is beginning to have a positive impact. “I do think that in the mainstream of economic and public policy, there is a realisation that things are probably going to get worse. There are crises and they do need to look for alternative methods to address them. And thus, our organization has never been busier, never been more in demand.

“There are now very traditional public policy makers interested in our ideas, and they think we can help unlock some of the problems we’ve got. So I think people are more receptive to it.

“There’s a loneliness though. There’s not enough money around for organisations like us. There should be many more in that space who sit between formal policy making and what’s happening in social movements because it is an important translation of knowledge and experience. It’s not academia; it’s not state bureaucracy; it’s something else – a third space. And that’s an important space we inhabit.”

The existing economic model is failing too many people and too many places. But it’s not a matter of if change will come, but when economic justice will be achieved.

As has been a theme from all the speakers attending the 2017 Global Street Paper Summit, it is easy to get bogged down in the negative, from the statistical data showing a further increase in social inequality, to the growing problem of food waste. But, leading on from all that negativity, there is an opposing theme of optimism. McInroy is perhaps that optimism’s greatest advocate, and he sees it in everyone.

“People react in ways that can’t be predicted. It happens across the world. We don’t know what new movement will occur that galvanizes people to react in different ways, which throws away the old paradigm and disrupts it. And that’s what humans are. We’re a restless species that doesn’t take things lying down. That’s what fuels my hope.”