By Nathan Poppe, The Curbside Chronicle

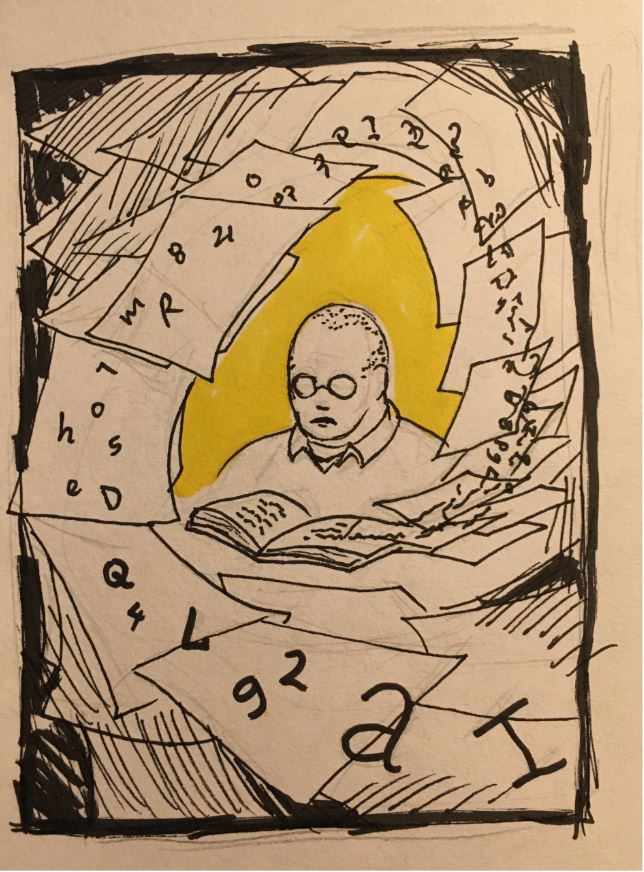

Fred Maxwell was speed reading on his porch, but he didn’t need to be in such a hurry.

Fred paused reading his book and surveyed his actions. He had been multitasking this whole time. He was sipping coffee, playing the radio and greeting neighbours. All while speed reading like he had an English report to turn in the next day.

“I’m trying to read something and enjoy it, but there I was skipping words,” Fred recalls. “I had gotten in the habit of never being where I was. I have to learn how to just be. You know, I struggle with that all the time. My ultimate goal is to just recover from a lifetime of being in a rush.”

Fred isn’t alone in experiencing increased feelings of stress as a result of isolation. Throughout the US, mental health treatment and addiction recovery programs have been disrupted — all while COVID-19 has sparked an increase in reported symptoms of anxiety and depression. In late June 2020, 40 per cent of US adults reported struggling with mental health or substance use, according to findings reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The New York Times dug into the study and learned that 5,400 people completed this online survey. Anxiety symptoms were three times as high as those reported in the second quarter of 2019, while depression was four times as high.

Fred found his veteran recovery group after a year of experiencing homelessness. He has attended meetings almost every Thursday for the past two years. When his weekly meetings were cancelled in March due to COVID-19, it was harder to be around people and difficult for Fred to express himself. For months, he said he didn’t share his feelings of isolation with anyone.

“I had focused more on the pandemic than my sobriety at the time. It was just a relapse in my mind. I restarted an old way of thinking, which made it seem OK to have one beer. Nobody would know. I’m just drinking in my quiet place. It escalated from there.”

He’s a widower and all six of his kids have lives of their own. He tells me that he can often feel warehoused — as if he has been put on a shelf to expire. He has felt the weight of depression during the pandemic, and he honestly didn’t think to call another veteran to talk about it. Life without his group meetings was tough.

“It’s just lonely,” he says. “It’s bad to be left with your own thoughts. The main advantage of being in a group is having a chance to express yourself, no matter how crazy you might sound. You say it out loud, and it helps.

“But if you’re always by yourself, then you can convince yourself of anything,” Fred continues. “A bad idea makes perfect sense if you’re isolated.”

Fred is extremely relieved his recovery group is back to meeting face-to-face, or at least mask-to-mask. They resumed their meetings in October. These sessions helped him feel less isolated and more connected to people who know what it’s like to have an unwelcome panic attack if an airplane flies too close overhead. It’s not the first group Fred has opened up to about his struggles with alcohol and isolation, but this one has been an especially good fit.

“It’s a great place to discover who you are,” he says. “It’s not magic, but it really helps … physically and mentally. It made a difference. Everything got better by just being with people.”

Guarding her sobriety

A bad idea had been staring down Lacie Wallace.

The Curbside Chronicle vendor, 45, was contemplating having a beer. The moment is a lot more dramatic if you think about every day of the two years she was able to avoid drugs and alcohol. She had so much going for her.

She got plugged into AA meetings about a year ago and also started attending art classes at the Homeless Alliance. On top of that, she became an OSU-OKC student and was on her way to receiving a retail floral design certificate so she could start working at Curbside Flowers.

Then COVID-19 hit. Everything in Lacie’s life slowed down. She took social isolation seriously right away and stopped leaving her apartment, but it left her feeling deflated and missing the activities that helped keep her sober. Her meetings and classes were paused because of safety precautions implemented in response to COVID-19. She soon reached for that bad idea.

“I had focused more on the pandemic than my sobriety at the time,” Lacie says. “It was just a relapse in my mind. I restarted an old way of thinking, which made it seem OK to have one beer. Nobody would know. I’m just drinking in my quiet place. It escalated from there.”

Lacie said she started drinking heavily and using hard drugs again. For three months, she was lost in her addiction and feared an overdose. Her faith is extremely important to her, and she prayed daily for a path toward sobriety. Then she heard an answer and something in her mind rebooted. It’s hard for her to say exactly what changed.

“If you’re always by yourself, then you can convince yourself of anything. A bad idea makes perfect sense if you’re isolated.”

Lacie entered a rehab clinic and gave an addiction recovery phone app a try. Sharing messages online didn’t compare to in-person AA meetings, but at least it was an outlet. A viable one that helped inspire her and humble her in the aftermath of a bender that could’ve been deadly, she tells me.

“You have to guard your sobriety,” Lacie says. “Yeah, you have to be true to it, so it’ll be true to you.”

In 2019, nearly 72,000 Americans died from drug overdose, according to the CDC. Overdosing has grown so much in recent years that it’s pushed down overall life expectancy in the US. This trend is nothing new. Deaths due to drug overdose in America have increased nearly fourfold from 1999 to 2018 — with opioid abuse looming large as the leading cause.

From January through March 2020, 19,416 Americans died due to drug abuse. That’s nearly 3,000 more fatal overdoses compared with the same period in 2019, according to NPR. These numbers are expected to grow as COVID-19 lingers throughout the US.

Building hope

Walker Milligan works as a therapist at a private practice in Oklahoma City. He’s in recovery himself. An important thing he’s learned from clients facing substance abuse issues is that drugs and alcohol are an effective coping mechanism. The catch? They aren’t efficient.

“Efficient coping strategies don’t happen naturally,” he explains. “They take practice and work. We naturally fall on the ones that are most effective in the moment. … I think people confuse rationality with what humans actually do. Our emotions, anxieties and pain don’t work in the realm of logic.”

Walker describes recovery as a practice. He often works with clients to re-frame their frustrations in a less judgmental light and helps them work toward self-acceptance and gratitude.

He asks me to imagine stepping off a curb and spraining your ankle. “Your mind might say, ‘I knew I shouldn’t have worn these shoes. I always slip in these shoes. I wasn’t even looking when I stepped off the curb like a moron,’” Walker says. “Does that help your ankle heal? Does that help get you to the doctor? No, but we focus on the negative all the time. … We think we have some control if we beat ourselves up enough.”

In many recovery programs, there’s already the added pressure to maintain sobriety for a set amount of time. Recovery should foremost be about building hope, Walker says.

“I think it’s worth re-focusing on any tiny, positive thing you’re doing for yourself. It’s about self-love and self-acceptance,” he adds. “Our society’s not great at that. We’re great at being hard on ourselves and being anxious.”

Growth in telehealth and outreach

Emma Wassilak has worked as a therapist at Sunbeam Family Services in Oklahoma City since 2014. The social services agency is one of the longest standing in the state and offers counselling, foster care assistance and a shelter for senior citizens. Emma has noticed social isolation causing increased stress, anxiety and depressive symptoms in clients — as well as increased numbers of people seeking services related to abuse or neglect.

These symptoms have led people to consume news to a point where they feel like it’s unsafe to stop watching it, while others have simply had a hard time enjoying life as much as they used to.

“I think it was a disservice to our society when we told people to be socially distant because what we meant is physical distance,” Emma says. “We are creatures of togetherness — introverts and extroverts alike — and we need each other.”

Emma is a clinical supervisor and also one of 15 therapists at Sunbeam. In addition to noticing a general increase of symptoms in clients, she’s also seen an uptick in employers realizing the impact of stress on their employees.

“It’s bad to be left with your own thoughts. The main advantage of being in a group is having a chance to express yourself, no matter how crazy you might sound. You say it out loud, and it helps.”

Sunbeam provides an Employee Assistance Program offering telehealth mental health services to Oklahomans, and it’s gaining popularity. With all of COVID-19’s downsides, Emma has noticed a silver lining — it has deepened the skillset of her co-workers.

“My staff is continuously having to do training to keep ahead so that we can support our clients, families and EAP partners safely and effectively,” Emma says. “We’re educating employers or groups of employees on how to do self-care both in and out of the workplace, so that they can sustain themselves and still feel effective in their work.

“We’ve been connected to more training opportunities, including suicide prevention via telehealth, which was not something that we had to think about before COVID-19 because, previously, those services all happened in person for us,” she continues.

Telehealth was something Sunbeam hadn’t embraced at all until March. It was a dramatic shift for them to pause in-person meetings for nearly three months. The shift to telehealth occurred rapidly — over the course of just two weeks in March.

“It seemed obvious in the interest of safety and the information we had at that time,” Emma says. “It wasn’t a decision we took lightly, but it was one we knew would allow us to continue providing services. … That need wasn’t going to stop.”

Nowadays, daily work is made up of taking Zoom calls and phone calls all day, while some in-person services at Sunbeam have resumed, Emma reports.

NorthCare faced a similar technological challenge. The non-profit clinic focuses on substance abuse as well as behavioural and mental health concerns for children, families and individuals.

NorthCare’s VP of Growth, Connie Schlittler, had a front-row seat for the transition to offering telehealth services. It was a challenge for her co-workers to juggle keeping everybody safe with offering virtual solutions to clients.

“NorthCare tracks any adverse events impacting our clients, including suicides,” Connie says. “Just seeing one is too much for us. I did not see an uptick among those we serve; however, we are aware there was an increase in suicides reported by the Oklahoma City Police Department in the spring.

“I do think people were disconnected. They were distressed and struggling,” she continues. “Social isolation isn’t good for any of us. For those with mental illness or a substance abuse disorder, it’s really not good for them.”

Many walk-in clients at NorthCare are experiencing homelessness and have barriers not only to affording a smartphone but also keeping it safe or fully charged. Connie says they provided iPads and cell phones to shelters like The Salvation Army to help clients manage telehealth meetings and receive crisis intervention.

NorthCare implemented a new text messaging system to communicate appointment reminder notices and last-minute cancellations because they were initially having such a high no-show rate, even with telehealth calls in place.

Outreach efforts also increased at NorthCare. A new crisis counseling group was created through federal funding. Adriana Wendland leads the team of four and is in the process of hiring an additional four outreach workers to connect people with mental health and social services throughout Oklahoma County.

Adriana felt the fallout of COVID-19 directly, as she lost a job in March and experienced unemployment for months before securing her new role at NorthCare.

“We have a group of people who are highly dedicated to helping others,” she says. “I can tell you that we really offer resources, hotline numbers and links to virtual support groups. We partner with utility companies, housing agencies, food pantries and transportation organizations. The main goal is to link people or companies to resources.”

A direct phone line to the crisis counselling group is in the works but, for now, people can reach out to NorthCare’s direct line. The hope is to ultimately reach isolated people and connect them to their immediate needs — no matter how small they seem.

“We want people to be comfortable with contacting us — even if it’s just for us to listen,” Adriana says. “If we can change someone’s life, then that’s all it matters. … We are people for people.”