Sitting in the café of Edinburgh’s National Portrait Gallery with Celia Hodson, surrounded by tourists, art lovers and some of the Scottish capital’s elderly community out for a spot of lunch, she has absolutely no qualms with talking, loudly and proudly, about a subject that, for many people in the UK, and across the world, is taboo – periods. But in our supposedly modern society, why is talking publicly about menstruation still off-limits?

“I just shake my head in disbelief whenever I’m asked that,” she says. “It’s bizarre, isn’t it? 50 per cent of the world’s population are, or were, menstruating, or will in the future. What is that all about?”

Her incredulousness is palpable. “I think it has something to do with British politeness, and maybe about control. In the UK, we just don’t talk about those things; we can talk openly about condoms, but not tampons. It all stems from this stigma around it being something yucky. I was on BBC Radio talking about periods recently, and one guy rang in and said ‘Thank you so much for ruining my lunch – that’s revolting’. I said, ‘Sir, didn’t you have a mother?’.”

Hodson talks about periods for a living. After many years working in the social enterprise sector supporting start-ups and working on policy, governance and infrastructure, she decided to start one herself. Hey Girls was the organisation that came out of brainstorming with her daughters about tackling period poverty – women living in a situation where they cannot afford sanitary products when it’s their time of the month.

Whether it be pads, tampons, cups, or whatever is your product of choice when dealing with your period, this basic health item can often be out of reach for society’s most marginalised, a situation which Hodson can relate to.

“It’s an incredibly serious problem,” she says. “I started Hey Girls knowing what it was like to bring up my kids on benefits. It’s not a great way to live – bringing up a family on long term benefits has a really detrimental effect on you as a person, on your self-esteem, and your confidence grinds away, making you think that nothing will ever change.

“It’s been a long time since I was experiencing that, but it’s harder now. People’s lives are so fragile: working on zero hours contracts, benefits stopped overnight. Women have to juggle paying bills, buying food, trying to make ends meet, and then having to worry about their period too.”

Until recently, period poverty, an issue affecting swathes of women across the world, was not in the spotlight. Women spend on average £13 a month on sanitary products, while one in ten UK women cannot afford them. “It has always been there. But women have found a way to manage – using newspaper, t-shirts, socks. It doesn’t even sound bearable.”

After generations of being unseen, period poverty is now firmly in the public consciousness. MSP Monica Lennon is leading the drive to eradicate period poverty in Scotland through a bill proposing that free sanitary products be provided to all. For a perfectly normal biological process to go unspoken in some family homes, it takes another leap to imagine it being spoken about in Parliament, but Midlothian MP Danielle Rowley spoke openly about her period in the House of Commons, drawing words of encouragement.

“Until all the language around period poverty came out, women thought they were alone in this; they had no idea there were others in the same situation,” explains Hodson. “I thought I was the only one making do, using loo roll, going into McDonalds to take napkins [points to the other end of the café] over there I’ve spotted paper napkins, okay I’ll take half of those!”

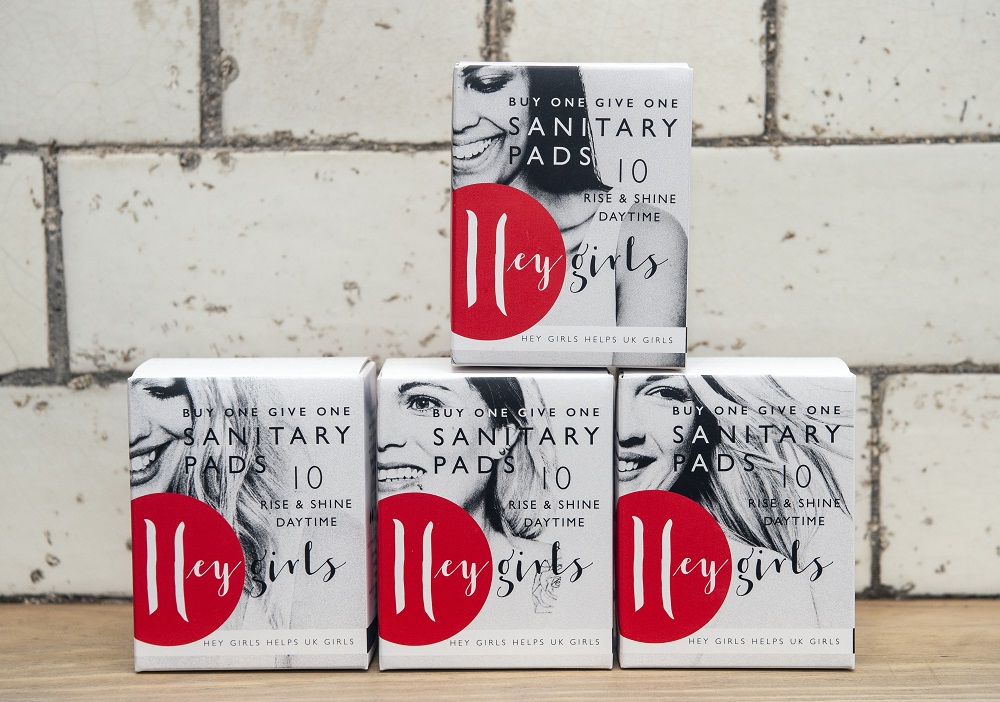

When Hodson began discussing with her two daughters, Becky and Kate, on how to tackle the problem, they came up with a three-pronged attack. First was the ‘buy-one-give-one’ concept, whereby a woman who can afford sanitary products purchases the pads from Hey Girls and, in doing so, one identical product goes to a woman who can’t afford them. “I’m not a very outspoken campaigning kind of person, but I’m a doer,” Hodson says, explaining the decision. “But we know how to retail and we know what products we like to buy, and we have a good network, so it seemed like selling a product and doing product donations was the best answer. When we started to explore it, the buy one give one model was the only answer. People think that’s done begrudgingly by customers, but actually people are very generous, and there’s a whole sister peace ideal around period poverty. It makes sense to do something good while you’re spending money on yourself.”

Next came the products themselves – a range of women’s sanitary items that were chosen by and designed specifically to the needs of women. Hodson explains: “There’s this balance between price and quality. You can buy pads, in particular, for next to no money, maybe 55 to 75p. But they’re high in plastic content, they leak, they’re scratchy, they give you a rash and you end up using twice as many as you would a good quality one. Just because you can’t afford the best, why should you have to use something that’s crap.”

Hodson and her daughters conducted their own focus groups in branches of Pizza Hut, flooding tables with all kinds of products, of differing qualities, with the women in the groups picking the best parts of each. What resulted was a product that women were comfortable with, was of a high quality and affordable, and was environmentally friendly.

Even the branding came out of these groups, with added flourishes that make the product even more socially conscious: messages of advice and encouragement from Hey Girls volunteers on the box, and a domestic violence helpline number on the inside lid. “The refinement process is one of the things we’re all about, and if it makes a difference to even just one person, it’s worth it.”

But the third prong of their model was missing. “We quickly realised, it’s not enough just to give product away. Yes, we have to make our product better, and take on the big boys, but also we need to do something around education. We decided we’d cover all of that. Our customers do the donating and we follow up behind with the educational aspect. Smashing all the taboos and having big conversations about periods.

“I’ve been trucking around the social enterprise world for a long while. When I was done with all that, I expected to retire, do a little governance stuff, join support bodies’ boards. But this conversation with my daughters inspired me. And so we spent the second half of last year building the whole business from the ground up. I just think if you’re going do something, you need to do it fully, not just give things away.”

It’s Hey Girls’ intention that, eventually, the educational aspect of their mission will mean communities pick up the mantel and go about spreading the facts of the issue around and getting people, of all gender identities, talking about periods. One such success story, Hodson tells me, is a school in Stirling, that has created their own period mascot, adapted their school motto to raise awareness about getting set for your period (“Be prepared…for your time of the month”), and enlists the enthusiasm of girls, boys, teachers and parents alike. “No shame, no stigma, just an everyday thing,” beams Hodson. “They’ve taken ownership of it. People powered change. We don’t need the government; we need kids, teachers and families.”

Despite having only been in existence since January this year, Hey Girls is one of the leading advocates in the fight against period poverty, with their products now set to be physically sold in supermarket chain Waitrose. Hodson says the reason people are connecting with it is due to the initial effort they put into creating a good product, while getting people to understand the good that destroying period poverty would have on society. “People are buying it because it’s a good thing to do. They re-buy it because of how good the product is. £3.25 – it’s not that cheap, so if it’s not good they’re not coming back. There’s an inherent good in creating these high quality products, but using the product to spread awareness of the message is also a good in itself. Then you have the fact that we are approaching this as a socially ethical business too – the environmental impact, the branding, the ethics of our suppliers and producers, and creating a supply chain that is completely made up of other social enterprises. It’s good, good, good, or as one person told me, it’s something fun, sexy, period and poverty all in one.

“When we talk publicly, it sounds stupid, but I throw sanitary pads at the audience. You should be able to get it out there. Having some fun with it means people are more open to talking about it. Because there’s still this huge stigma around discussing it. It affects your relationship with your family. When your period starts, you’ve become a young woman, you could get pregnant, and so this fear develops. And then there’s all the horrific myths about what happens – you’re going to lose pints of blood, you can’t exercise or go swimming, you can’t wash your hair or you’ll go mad. Really ridiculous stuff builds up, like gossip. We don’t have an honest conversation about what’s happening to the body and what your menstrual cycle looks like.”

Hodson prides herself, and the business, on the fact that they are plugging a gap that, despite all their progress on the issue, the government can’t reach. “The very nature of government process is slow, whereas, when we decided to do this, we had set up Hey Girls by the length of a train journey from London to Edinburgh. While all the campaigning goes on, and the government figures out what it’s doing, we just get on with it. A lot of social enterprises exist in that little gap, those cracks in the market, doing something good.

“But if all of what is getting done leads to the creation and implementation of a policy that means Hey Girls is no longer needed, then fabulous.”

And while period poverty can hit any woman in a vulnerable situation, one particular affected group is homeless women. “When you’ve got a period at home, you snuggle up on the sofa with a large bar of chocolate, watch some Netflix, and maybe bite someone’s head off, that’s the typical picture,” says Hodson. “Imagine not being able to do any of those things, not being able to have a shower? So the way people manage on the streets is through free bleeding, not using anything. I’ve spoken to girls who use dry grass cuttings, leaves, paper bags, anything. Or if they do get some product, they use it for days and days.

“It’s really bad. A significant number of folks on the street have a low level of literacy, so there’s no point in handing them a leaflet – if they weren’t told about their periods by a parent, then they might not know about it at all.”

Despite not having the capacity, or as Hodson admits, know-how to help women on the streets, by donating their products to local food banks, church and youth groups, and other social enterprises and charities like the Simon Community and Social Bite, as well as passing onto support workers specially designed educational materials, Hey Girls has a hand in reaching women that might otherwise be overlooked. (The investment arm of UK street paper The Big Issue, Big Issue Invest, is also a supporter of the work done at Hey Girls).

Come September, Hey Girls will only be nine months old, but when the Social Enterprise World Forum (SEWF) arrives in Scotland, Hodson has been tapped to share her expertise with delegates, and she is laudatory about the way that Hey Girls has been allowed to thrive in the country.

“Scotland’s got its act together in a way that other places haven’t,” she says. “Coming here, I found it an incredibly supportive space for social enterprises. They’re not pushed into little silos, there’s a connectivity – taking people who run social businesses on a journey, allowing them to develop their ideas, and helping them through funding. It’s a very visible pipeline.

“The government is quite rightly throwing money at social enterprises, seeing them as operating in pockets where lawmakers can’t, and becoming a significant part of the economy. It feels like a really fertile space. There’s not this cutting off of ambition either. Years ago in Scotland, or even in other parts of the UK now, they would have told a business like us, ‘Steady on, you’re getting a bit big for your boots, you need to first pilot this for three years’. Now it’s more like, ‘That’s a mainstream idea that actually has social impact at the end of it’. They’re more willing to take a punt, and that’s pretty cool.”

With all her experience in the sector, Hodson is able to pinpoint the exact reasons why she believes Scotland has developed into a leader in the social business sector. “Scotland is starting to monopolise on the intention and goodwill of big bucks businesses who are deciding they can benefit from giving something back.

“And there are a lot of really smart people in universities, Gen Y and the next lot, wanting more out of life. They’re saying ‘Yes, I want a good job and to make money, but I also want to do more, and know that my employer is making a difference’. So, it feels like it’s all coming from academia, enterprising individuals, corporate, government, everywhere. A very connected picture. Scotland really is a unique space, and it needs to shout about that. The forum gives us that option.”

Hey Girls seems to be spearheading a long overdue turnaround in how women’s periods are perceived by society as a whole. Some have even described it as a trend. “Trend is probably a bit of a disparaging way to describe it. But it is certainly trending,” says Hodson. “I think it’s a movement; something happens and it just takes the cork out of the bottle and people say ‘No, I’ve had enough of this’. It’s so easy to make a difference. It is trendy and a lot of people jump on the back of that. All that chitter and celebrity that goes around it – well, so what if it makes a difference.”

INSP Members can download this article from the INSP News Service here.