Andy Murray is biding his time.

Britain’s most successful tennis player since the late 70s has been sidelined with injury for nearly a year, but he’s in no rush to tell everyone exactly when he’ll be back.

As of the time of writing, Murray had yet to confirm that he would return in time for Wimbledon – which he has won twice – and had only tentatively reassured his fans, and the baying UK sports media, that he was committed to competing in the Queen’s Club Championships two weeks prior to the start of the historic Grand Slam. Rumours continue to circle that he will be back on the grass court by 11 June, at a tournament in Rosmalen in the Netherlands.

His return may be up in the air, but what’s clear is that the recently-turned 31-year-old wants to ensure that, when he does make his comeback, he is fully fit.

And after such a celebrated career, sparring with some of the best tennis players in the men’s game, making it to countless tournament finals, and racking up honours both on the court (three Grand Slam titles) and off it (a knighthood), it’s no surprise that Murray does not want to rush his recovery from a debilitating injury that many might not make it back from.

In the meantime, the Scot, who was born in INSP’s home city of Glasgow and grew up in the central belt town of Dunblane, has busied himself with other endeavours, whether its playing up his now famous brand of dry wit on social media, or, more seriously, running his newly established sports management company, 77 Sports Management, the roster for which already boasts promising young British tennis stars, Katie Swan and Aidan McHugh, and sprinters Shannon and Cheriece Hylton.

In a sport that often values charismatic individuals and larger than life personalities more highly, Murray, who doesn’t always live up to that kind of ideal on the court or in post-match interviews, has battled hard to prove that competitive success speaks louder than words. But, when he does air his views on subjects that are close to his heart, from the disparity in tennis between genders, to his work with charities like UNICEF and Sport Relief, he speaks with a consideration and intelligence that his more outgoing peers may lack.

After promising to deliver us some of his grandmother’s renowned shortbread (“I think it’s so famous because it has so much sugar in it!”), Murray took time to speak to INSP about his experiences of street papers across the world, the transformative power of sport and triumphing over adversity, while remaining tight-lipped about the specific details of his return to the tour.

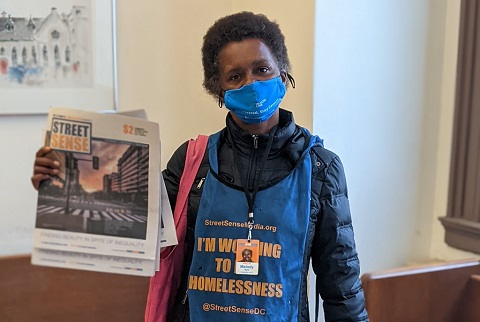

INSP: You grew up in Scotland, so I imagine you came into contact with The Big Issue and its vendors fairly often. What was your perception of street papers and their vendors when you were younger, and how has that changed as you’ve gotten older and spent time away?

Andy Murray: I’ve always thought that they are a great initiative, I think it’s important to help those that are finding things tough. Growing up, I didn’t have too much of an understanding of the Big Issue and what it was all about, but as I’ve got older and read more about it, my perception of it has also changed. I’ve done a few interviews with street papers over the years as well, so that has helped enlighten me.

You travel around a lot – have you come into contact with marginalised people selling street papers in other parts of the world? Do you ever buy them?

When we travel we tend to go from hotels to the tennis court and back again, so we don’t really see that much of the places we visit, however I like to chat to the different sellers and always buy one.

What’s your perception of homelessness, and how it is tackled, both at home and abroad?

It’s obviously a very sad thing, but I can also appreciate it’s something that, for some people, can become unavoidable through personal circumstance. It’s great that it’s more widely discussed and that more is being done to help. I know a lot of the big UK cities particularly have been working quite hard to try and get more people off the streets and into temporary housing and shelters, particularly as we had such a cold winter this year. I hope that the efforts and awareness around it continue to improve; no one should need to be homeless, so it would be great to see it become a thing of the past.

Whatever happens, and no matter how tough the situation, never give up

Sport is often something which helps to inspire people, and pull talented individuals who are living in poverty out of their situation and onto great success. Do you think this story still rings true?

Of course, sport unites people all over the world and you hear of different stories all the time about the ways sport has helped people change their lives for the better. Whether it’s used as a coping strategy, a socialising tool or a method of lifting yourself out poverty, it inspires people and I love that.

What’s your opinion on the role of sports in the de-marginalisation of vulnerable groups? Does sport have a greater role in communities, apart from professionally engaging a limited number of people?

Sport has the power to change the lives of those that play it. It can help create safe spaces and the exercise and fitness element is also important. Team sports, in particular, can instil important shared values, things like teamwork and determination. These things can help not just in sport but in people’s lives and wider society.

Your success seems to be a good jumping off point for the UK to get more people involved in tennis, and all sports. Do you think the groundwork has been properly laid here to produce more Andy Murrays?

It’s definitely getting better. There’s been a bigger effort over the few years to get more kids into tennis in Scotland, my mum [Judy Murray] has had quite an active role in that, through creating programmes, campaigning for more indoor courts, and working to try and build her own tennis centre. As with anything, building a legacy takes a lot of time and effort, and I’m hopeful that over the coming years my family can keep inspiring more young people, not just to play tennis, but to make healthier choices in life.

As a prominent person – especially an athlete that a lot of people look up to – do you feel a need to show a certain level of responsibility and professionalism? Do athletes, and other people in the public eye, have a duty to do this generally?

Definitely. We are in a very privileged position as professional sports people, and I believe it’s our responsibility to make sure we’re inspiring and setting a good example for the next generation. It’s also been important to me, that if there’s something I don’t agree with, to speak out. I always treat people with respect and manners are very important – I’m trying to curb some of my colourful language on the court as well

There is a certain amount of adversity that seems to be interconnected with the life of a professional sportsperson – whether it’s facing up to injuries or the mentality required to compete, and win, on the highest stage. How do you cope with adversity, and what advice would you give to others in their struggles against it?

Everyone goes through tough times, which can sometimes be magnified if you are a public figure. I like to tackle adversity head on, the quicker you address the issue, the quicker you can work to fix it. Whatever happens though and no matter how tough the situation, never give up. You’ve got to be true to yourself and if you’ve given everything you have then you can be proud, regardless of the result on the pitch, tennis court or in life.

You’ve been a willing critic of gender inequality within tennis and how it is approached by the media [Murray has made headlines calling out broadcaster John Inverdale for misinformed comments about Olympic gold medal winners, and questioning criticisms of his then coach Amelie Mauresmo, while his male coaches were seemingly absolved of responsibility]. How big a problem is it and do you see any sign of it improving? Do you think your public comments on the issue make any difference?

I’ve never set out to be a spokesperson for women’s equality, it’s just something that I feel it’s important to speak about. I’ve never understood why someone’s gender should ever be an issue – we should be judged as people. Relatively recently, my experience of working with Amelie Mauresmo gave me an insight into the treatment of, and attitudes towards, women in sport. I started working with Amelie because she was the right person for the job. However, it became clear to me that she wasn’t always treated the same as men in similar jobs, and so I felt I had to speak out about that. In general, I think the future is positive. We’ve got more female role models than ever before and more people championing the rights for women in sport, so things are moving in a positive direction.

You recently received a knighthood – was that an easy thing to accept or did you have doubts? Of course it’s a huge honour, but not everyone is willing to take it on.

It’s obviously a big responsibility, but it was an honour to be awarded it, and it’s something I’m very proud of. I never thought it would be something I’d achieve so it’s a great feeling, however I’d still rather people just called me ‘Andy’ (laughs).

You’ve done various work with charities that focus on children and young people – is this something you’ve always been passionate about, or is it something you’ve grown into, especially now you have a young family?

It’s always been really important to me to know that I’m giving something back. I’m incredibly lucky to have the career I have, and I’ve never wanted to take that for granted. If through my success, I can help people build a better live for themselves, raise awareness of a particular cause or issue or help those in need, that’s important to me. It’s something I’ve always been passionate about, but it’s definitely got stronger since having children. Some of the work I have done with UNICEF, particularly, in helping children that have been uprooted from their homes and forced to flee conflict was a direct response to the awful images that were being broadcast on the news a few years ago. I’m also passionate about protecting animals and our planet through the WWF and United for Wildlife.

You’ve started a sports management company – what are your goals for this in the long term? Is this a sign that you’re looking towards life after winning grand slams and being on the court every day?

Not really, it’s something I had wanted to do for a long time. It’s important to me that the agency is very much athlete first in everything we do – you’d be amazed at how many agencies don’t do that. We want to help and support athletes and I’d like to be able to mentor and advise on the valuable lessons I’ve learnt in my career.

After a long struggle with severe injury, what are your hopes and expectations upon your return to the court?

I’m really looking forward to being back on the match court again. I’m taking my time with this rehabilitation period, I want to make sure that I’m 100% ready when I do return to compete at the highest level, I’m leaving no stone unturned. I’m not putting too much pressure on myself in terms of expectations, I just want to be back on the court playing and enjoying myself.

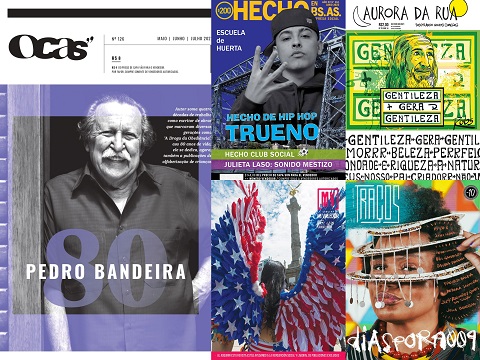

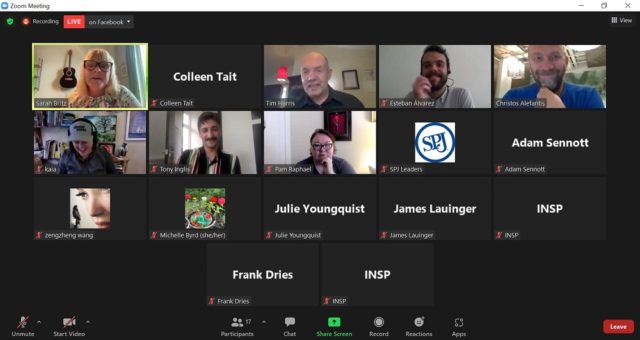

INSP members can download this story from the News Service here.