By Caleb Diamond and Joris de Mooij, Street Sense Media

The COVID-19 pandemic has created and exacerbated an unprecedented number of crises in the United States, from a public health emergency to a record-breaking economic recession. Not surprisingly, the coronavirus pandemic topped an August Gallup poll that asked Americans what they considered the most important issue facing the country today. Contradicting long-standing thinking about how and why people vote, non-economic problems have emerged as the top priority for the US public this cycle; the same Gallup poll found that more respondents ranked government leadership and race relations as the most important issue facing the country today than the economy in general. The presidential campaigns of President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden have reflected these shifting priorities.

While the pandemic continues to rage and election season enters its final weeks, the country’s need for policies and investment to support a massive increase in affordable housing is notably absent from the headlines. Adjusting for inflation, the median cost of housing has steadily increased since 1960, while median wages have not kept up since 1970, according to the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. In August, a report by the Aspen Institute, a non-partisan research organization, estimated that 30-40 million people could be at risk of eviction by the end of the year.

Issues related to poverty and homelessness have long been pushed to the periphery of presidential elections. But with the housing crisis on course to be the most severe in history, they are of vital importance to a record number of Americans. A recent series of tweets from Trump accusing Democrats of attempting to destroy the suburbs and an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal by him and Ben Carson, his secretary of housing and urban development, have potentially opened a new front in the presidential race—affordable housing and homelessness.

How do the two presidential contenders plan to stop and reverse issues related to poverty and homelessness, such as the rising number of evictions in the country? Like much of their campaign platforms, the two campaigns differ wildly on their approach to this issue.

The Republican platform

Since even before taking office, Trump has used the image of rundown, crime-stricken cities led by Democrats to his political advantage. Last year, he threatened federal intervention in California’s homelessness crisis, telling reporters, “We can’t let Los Angeles, San Francisco and numerous other cities destroy themselves by allowing what’s happening.”

Despite Trump’s rhetoric about this issue, there is little reference to it in official party and campaign policy platforms. In a Trump campaign press release that outlines 54 broad policy aims for a second term, not a single one of them addressed housing or homelessness. The Republican Party did not publish a new platform in 2020, instead re-releasing the 2016 version, which made broad gestures in support of deregulation and criticized government-sponsored mortgage financiers Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, as well as the Federal Housing Authority, as examples of wasteful federal spending rather than offering specific policy proposals to address homelessness.

What the Trump administration has recently released is a report from the Council of Economic Advisers, an agency within the executive branch charged with helping the president formulate economic policy. The September 2019 document offers insight into his administration’s views of homelessness.

Much of the focus of the report is on regulation, arguing that it both hinders the development of additional housing to meet demand and then increases the price of homes that are built, increasing homelessness as a result. To combat this factor, the report echoes a June 2019 executive order that suggested deregulation in a range of areas, including but not limited to zoning, energy and water efficiency mandates, and rent control, among others.

The report also claims that more tolerable conditions for sleeping on the street increases homelessness. While a city’s individual political environment — as well as its physical climate — plays a major part in conditions for sleeping on the street, the report calls for greater support for law enforcement. “Policing may be an important tool to help move people off the street and into shelter or housing,” the administration’s report states. To address the root causes of homelessness, it cites criminal justice reform efforts, including increased emphasis on treating mental illness and reducing drug abuse and continued support for the First Step Act, which eased federal sentencing guidelines.

The report also takes aim at long-standing principles Democratic policymakers in particular have embraced in the fight to reduce homelessness: right-to-shelter and a housing-first policy, which prioritizes finding housing before addressing other problems, including finding employment and attending substance abuse issues.

“While shelter is an absolutely necessary safety net of last resort for some people, right-to-shelter policies may not be a cost-effective approach to ensuring people are housed,” the report states, arguing shelters of a sufficient quality may present a more desirable option than long-term housing.

The document also calls for federal and local governments to rethink the housing-first approach. In the Council of Economic Advisers’s view, “by reducing the number of homeless people through programs that don’t set any preconditions or requirements for their participation, Housing First policies might generate outcomes that actually increase the homeless population,” summarized CityLab contributor Kriston Capps. In short, the report calls for policymakers to reconsider these interventions and consider a deregulatory approach instead.

The Wall Street Journal op-ed co-authored by Trump and Carson similarly targeted government regulation but is a far more political document than the Council of Economic Advisers report. The op-ed extends the argument to say current policies threaten the suburban lifestyle and are ineffective for reducing homelessness. Trump and Carson take credit for rolling back the Obama-era Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) regulation, writing, “we reversed an Obama-Biden regulation that would have empowered the Department of Housing and Urban Development to abolish single-family zoning, compel the construction of high-density ‘stack and pack’ apartment buildings in residential neighborhoods, and forcibly transform neighborhoods across America.” However, it is unclear whether AFFH would have resulted in such action.

In reality, the AFFH regulation “tells jurisdictions that receive federal housing funds that they have to assess what patterns of housing discrimination they have and then come up with a plan to diminish them,” NPR’s Danielle Kurtzleben writes. The policy was heralded as a long overdue response to structural racism in federal housing policy when it was implemented in 2015, but due to the Trump administration’s repeal of the rule in 2018, its effects were never fully analyzed. Later in the op-ed, Trump and Carson write that “it would be a terrible mistake to put the federal government in charge of local decisions — from zoning and planning to schools.” Like the CEA paper, the op-ed makes clear that the Trump administration’s solution to the homelessness crisis lies not with federal government action, but in deregulation and local government.

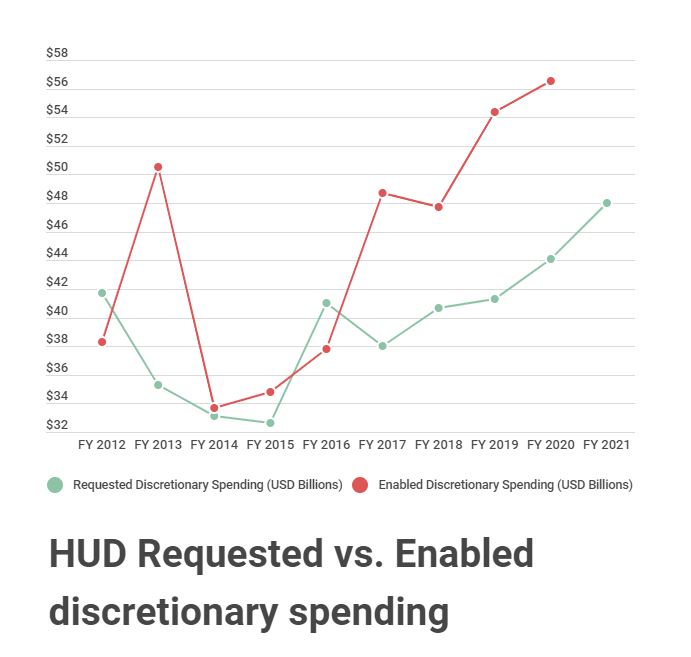

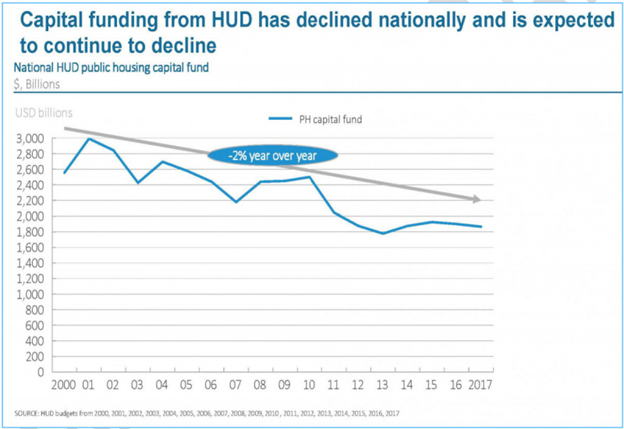

The appointment in December 2019 of Robert Marbut to head the US Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH), which coordinates strategic cross-department efforts to prevent and reduce homelessnesss, is also revealing of the current administration’s philosophy on public housing and the housing-first approach. Though, disinvestment from public housing is not unique to the Trump administration.

Marbut, who has worked as a consultant to cities desperate to find solutions to homelessness, has been an outspoken critic of the strategy. “I believe in Housing Fourth,” Marbut said in 2015.

In the past, Marbut has been involved in promoting a number of controversial programs that provide a glimpse into his “velvet hammer” approach that includes a ban on panhandling. Most famously, he created a shelter complex called “Haven for Hope” in San Antonio, where people had to sleep on the ground until they passed drug tests. Although much of the intellectual framework of the Trump administration’s policy toward homelessness is coming out of the White House, Marbut in his role as the homelessness czar plays a significant implementation and coordination role. He will undoubtedly impact the formulation of policy in a second Trump term.

The Democratic platform

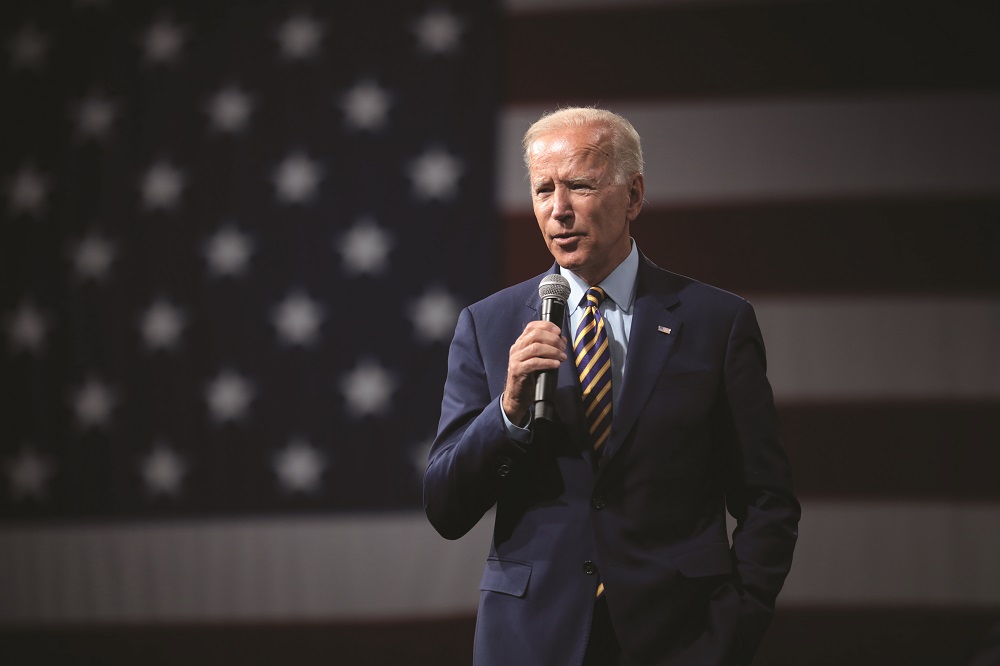

Joe Biden’s campaign and the Democratic Party offer a starkly different approach to the homelessness crisis. The 2020 Democratic Party platform affirms support for the housing-first approach and argues that “government should take aggressive steps to increase the supply of housing, especially affordable housing, and address long-standing economic and racial inequities in our housing markets.”

Biden’s election platform offers more detailed proposals than the broader Democratic manifesto. One of his major proposed reforms in terms of housing is the establishment of a $100 billion Affordable Housing Fund to construct and upgrade affordable housing. This reform would increase funding for the Housing Trust Fund by $20 billion, expand HOME grants for affordable housing investments and rental assistance (which Carson tried and failed to cut), expand the Capital Magnet Fund, provide money to make homes more energy efficient, and offer incentives for local authorities to build affordable housing.

Biden argues for reimplementation of the AFFH rule that Trump suspended. He also promises to invest $300 million in “Local Housing Policy Grants” to give local governments the technical assistance and planning support they need to eliminate exclusionary zoning policies and other local regulations that limit high-density housing.

As far as addressing homelessness specifically, his platform echoes the Democratic Party’s call to take a housing-first approach. Biden says he will work to pass Representative Maxine Waters’ (D-CA) Ending Homelessness Act. The bill would invest $13 billion toward addressing the homelessness crisis, including $5 billion for McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Grants — the U.S. government’s largest homeless assistance program — as well as create, in theory, 400,000 additional housing units for people experiencing homelessness. Like Trump, Biden references the need for criminal justice reform and reducing recidivism as a crucial factor in sustainable housing solutions.

Other noteworthy proposals include providing Housing Choice vouchers to every eligible family; expanding the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, which incentivizes the construction of affordable housing; enforcing regulations on financial institutions that employ discriminatory lending practices; and expanding transportation options.

Looking beyond the proposals, Biden’s platform is peppered with references to the racial disparities inherent in the housing crisis, the civil rights of LGBTQ individuals and victims of domestic violence, and a need for energy-efficient and climate-resilient housing. Trump’s White House plan, on the other hand, hardly mentions racial inequities, and his Department of Housing and Urban Development has proposed to change an Obama-era rule that required single-sex shelters to accept transgender people. Climate regulation is mentioned in the White House report, as well as the 2016 RNC platform, but from the view that it contributes to the lack of supply and rising cost of housing.

While Biden will most likely focus on Trump’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and what many Democrats perceive as leadership failures, he will also undoubtedly hammer Trump on climate and race relations. According to an August Pew poll, registered voters trust Democrats on these issues by 31 percentage points more than Republicans on the climate, and 12 percentage points more on race relations, respectively. Housing is a potential avenue for Biden to incorporate these issues into his platform.

Competing visions

Like on so many topics this election, the two candidates offer vastly different views of how to address homelessness in the United States. Trump’s record and statements show he is skeptical of government fiscal intervention and the housing-first model and supports a deregulatory approach, whereas Biden advocates for the federal government to play a much larger role through greater funding and rulemaking.

With so many flashpoints leading up to the election, it is still unclear whether affordable housing will receive much attention as the campaign season enters the final stretch. Just two of the 11 Democratic Primary debates featured in-depth conversations about housing policy. But with politicians employing increasingly politicized rhetoric about the suburbs, this issue may bubble to the surface. Regardless, these competing visions on housing policy will have tremendous consequences for the millions of Americans experiencing homelessness or without access to affordable housing.