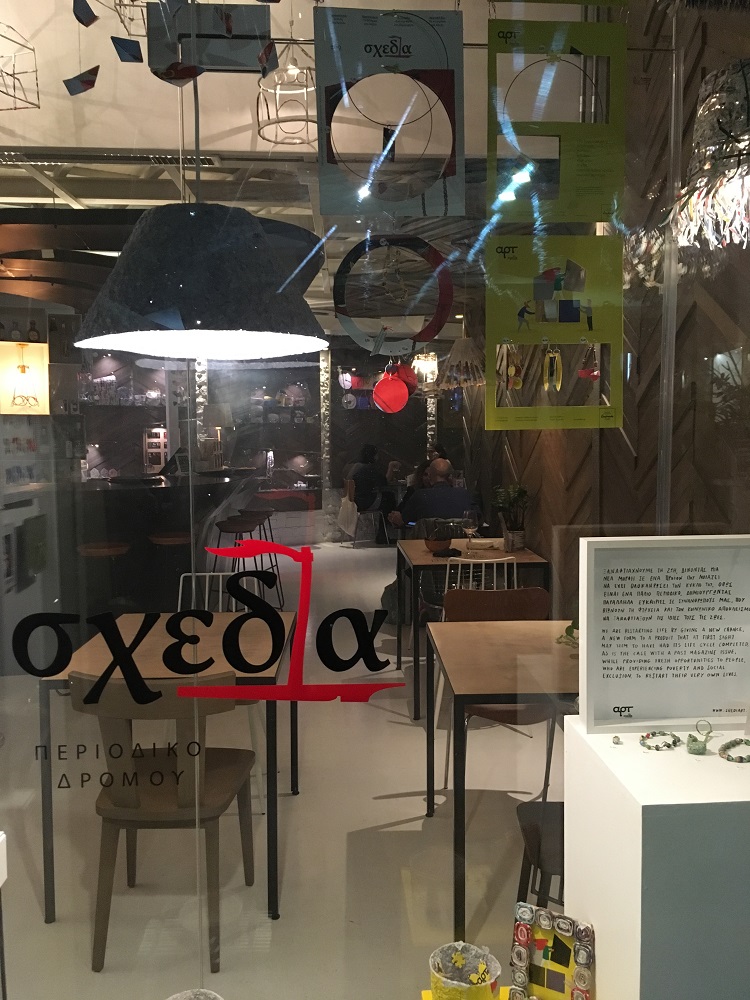

In the shadow of the Acropolis, on one of the busiest street corners in central Athens, attracting Greeks and tourists alike, Shedia, the country’s street paper, is a major presence. Vendors populate the area, next to churches and souvenir shops, always visible. But the multi-storey complex of Shedia Home also catches the eyes of passers-by, even as it sits amongst swankier mainstays of the area.

Shedia Home is the culmination of a long in fruition dream for those behind the street paper, namely its director Chris Alefantis – a literal home for Shedia and all its parallel social projects to be housed in. “It’s true that having all these projects going, separately, may have worked,” says Alefantis. “But it wouldn’t have been the same. The whole of Shedia would not have thrived the way that we hoped it would and now is.”

Originally a street soccer team, and then a street paper by 2013, Shedia has grown into something much more. The complex not only contains the editorial and distribution offices of the magazine, putting up journalists, with a steady stream of vendors – 100 based in the city, and an additional 50 in Thessaloniki in the north – moving in and out of the building at all hours of the day, but also the workshop for Shediart, its street paper upcycling project, and even a bar and restaurant. That’s not to mention its still running street soccer project (300 pass through it annually), a basketball team, a running group (which encouraged nearly 300 vendors, staff, associates and supporters to participate in the last Athens marathon), city tours, a theatre group, occasional writing workshops and even a pétanque team. The organisation is multi-faceted and, in all aspects, is providing work and character building for those who are homeless, living in poverty, unable to find employment or otherwise vulnerable and underprivileged.

Quality and accessibility

Entering the ground floor bar and restaurant, it’s clear that its existence is built upon Shedia’s principle of creating projects that people want to use, enjoy and put their money into because they are of a high quality, as opposed to out of charity. It is a chicly designed oasis from the exciting chaos of Athens’ bustling streets, all cool air and straight lines. The food and drink is made and served up by the project’s beneficiaries, all of which have been trained by Michelin star chef Lefteris Lazarou, who runs the restaurant Varoulko in the city.

“We have seven people working here currently, most of them former Shedia vendors from underprivileged backgrounds,” explains Alefantis. “The oldest is 62-years-old. We’re very happy that, even at that age, we are able to give such people a chance.”

People who have become socially excluded in their later years is common across all of Shedia. To get involved, says Alefantis, “they must simply want to work. The only cooking ability they need is basically to be able to boil an egg.”

Downstairs in the kitchen is Nikos Theodoridis, a former vendor now utilising trained skills to rustle up the top class meals being served to diners. After losing his job as an engineer due to the Greek economic crisis, selling street papers gave him another chance to earn an income. Cooking is something else he has embraced.

“It’s a beautiful experience,” he says. “Cooking is something new for me and has nothing in common with my previous jobs, but I like it because cooking involves imagination. There is a bit of freedom in it. I like thinking outside the box and cooking allows you to be creative. This is very important for me. Besides earning a salary, our spirits have been lifted. People see us differently now. It’s like we have come into being.”

The actual bar itself is designed based on principles of thoughtfulness, accessibility and environmental friendliness. Many of the utensils and dishes are products made upstairs in the Shediart workshop from upcycled magazines. There are menus in braille and audio formats for those who are visually impaired. Tables and bars are lowered for easy access to wheelchair users. Small details like coat pegs in the bathroom – again, well-placed for accessibility – are evidence of the careful approach to its creation. One person with additional needs, recalls Alefantis, said it was the “first bar he could actually take a piss in.”

There are decadent flourishes too – reasons why customers will keep coming back. Aside from the genuinely delicious Greek food, there are cocktails concocted by an award-winning bartender and playlists soundtracking the atmosphere curated by local DJs and producers. Shedia Home has already won a coveted ESTIA award.

A bar and restaurant may seem far removed from the work of a street paper, but Shedia ensures everything is connected. Vendors come and go, rubbing shoulders with other customers, benefitting from the “suspended coffee” system – a paying customer pays forward for a vendor, or other person in need, to receive drinks for free – and model houses (unsurprisingly, created from upcycled street papers) hang from the ceiling as you enter. Each one represents a person who has attained permanent accommodation since joining Shedia.

“I come to the work with love”

Directly above the restaurant sits the colourful jumble of the Shediart workshop where unsold editions of Shedia are stripped, sliced, pulped, weaved and moulded into useful objects of all shapes and sizes, from bowls and coasters, to lampshades and clocks. There’s even a Shediart dress hanging from the roof. “As far as I know, we are the only print media outlet in the world that upcycles our publications rather than recycles,” says Alefantis. “There’s more social, economic and environmental value doing this. It is a project we want to take to the whole world.”

Inside the workshop sits Katrin Kretschmer, one of the individuals behind the idea. “There were so many old magazines in storage and no one really knew what to do with them,” she says of the project’s genesis. “If you bring them to a recycling plant, you get very little in return for them and it is quite a job to transport them. It’s better than burning them, but there’s no real benefit for any person, which is what they were printed for in the first place. So, we thought, is there an alternative?”

Kretschmer started experimenting, devising techniques to turn the paper in to useful, aesthetically pleasing items. “All the raw materials are environmentally friendly – the varnishes, the glues, the fabrics, the ceramics. We could do this using chemical substances, but that defeats the purpose. It’s social as well as environmental,” adds Alefantis.

“We then invited the Shedia vendors to come to learn at workshops,” continues Kretschmer. “They were open – anyone who was interested could come just to see if they took an interest in handicrafts and being creative. But we didn’t say anything about creating jobs in the beginning. No one was excluded.”

Eight people were initially brought in for training, and two of them, Vanessa and Christiane – who are happily gluing and pasting away at half-crafted items finally taking shape as we chat – were taken on as Shediart employees.

“When we opened the place, we could give full employment, with all the entitlements,” says Alefantis. “It’s even beyond the situation with selling the street paper – this is full-time employment on a full wage. We hope we will have the business to not only sustain the two positions filled by Vanessa and Christiane, but also employ more.”

Christiane, 61, has fought through drug addiction and spent time in prison. Watching her work and talking to her at Shediart, it is clear that she is not only happy with the income she is now receiving (she used to sell the street paper) but thoroughly enjoys the work. “No matter how difficult an item is to make, I come to the work with love,” she says.

But Shediart isn’t just about creating and selling a product. Vanessa and Christiane have also been trained to teach the techniques to others. On the day of the visit, we attend a workshop with them, located at the original Shediart workshop, tucked away in a small unit in a nearby city centre arcade that lets out shops to local social projects. The participants are refugee children brought along by charity Caritas. They mould pulp into little bowls, their mothers watching on in glee. The joy on both the faces of the kids, and Christiane and Vanessa, is infectious.

Socially useful

Shedia Home seems to be constantly teeming with people. It is flourishing, though Alefantis wants to make clear how complex a journey it was getting to this point, and how much work there is left to do.

“We still have many challenges,” he says. “It’s always a challenge to be sustainable. We are healthy, but this is a very full on task day-to-day. We are rarely sat at our desks; we are always running around.”

Regardless of which project they’re brought into, Alefantis believes the most important next step is reaching more people and bringing them on board.

“One of our social tour guide lives in a [municipally run] shelter,” he explains. “In this shelter there are over 100 people, but only two or three are part of Shedia. I am convinced that, if all of them were with us, their hearts and souls would be much happier. They would have five euros in their pockets to buy their own cigarettes, and they’d get all the benefits you get from being part of a street paper.

“The reason they don’t come here is because they are institutionalised. They have given up. They think, ‘this is it for me’. So, what we say to the City of Athens, and many other councils, is it’s amazing what you do, providing shelter and food every day, but it’s not enough. You should not allow your shelters to become a human parking lot. Let’s work with them through the kind of social projects we have expanded to offer so they become energised, empowered, and motivated. This is global, I think. We are continuing to try and move on, to come up with more, better ideas, to become more socially useful.”

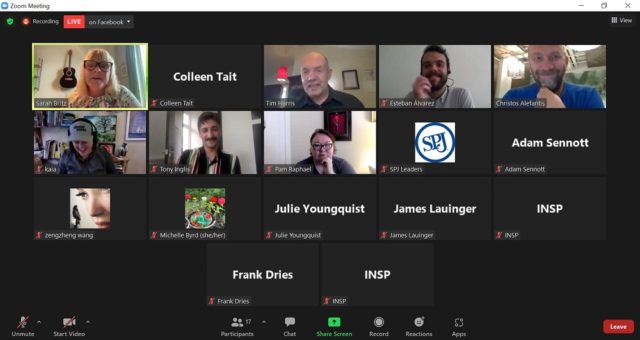

INSP members can download this story here.